Former Vallejo police union president Mathew Mustard has left the Vallejo Police Department, Open Vallejo has confirmed.

The former sergeant detective retired on Dec. 14, according to a spokesperson for the California Public Employees’ Retirement System. Mustard, who was on medical leave at the time of his retirement, quietly left the department without the traditional sendoff from his colleagues over police dispatch broadcasts, according to a review of radio traffic and sources with knowledge of the matter, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss internal personnel matters. A Vallejo police officer for 23 years, Mustard served as the president of the powerful Vallejo Police Officers’ Association from 2010–2019.

Mustard made headlines last year with the release of the Netflix documentary “American Nightmare,” which chronicled the 2015 kidnapping and sexual assault of a Vallejo woman, Denise Huskins. As the lead detective, Mustard accused the woman’s now-husband Aaron Quinn of murdering her during a nearly 18-hour interrogation, while allegedly ignoring key evidence that could have led police to her sooner. When the kidnapper released Huskins in Huntington Beach, Vallejo police falsely suggested her ordeal was a hoax.

The documentary placed an international spotlight on the embattled detective, who leaves behind a legacy in Vallejo steeped in controversy.

Mustard did not respond to requests for comment.

‘What will it take for you to call this a homicide?’

On Aug. 8, 2012, Vallejo police responded to a report that a woman had fallen in her motel room after choking on food. Upon their arrival, first responders found Jessica Brastow lying unconscious on the floor in her own vomit, according to public records.

Brastow, who was pronounced dead at the scene, had injuries to her wrists which first responders believed were from being tied up. First responders also found a sock with blood and saliva in a trash can. Michael Daniels, Brastow’s boyfriend, told police she had only been down for two minutes before he called 911, but first responders noted she was cold to the touch. Daniels had fresh, bleeding injuries to his forearms, according to public records.

The case would ultimately prompt the California State Bar to suspend the lead prosecutor’s law license for misconduct. While Mustard was not the subject of the investigation, a State Bar Court ruling would find that Mustard pushed for Daniels’ conviction for murder, even when a county forensic pathologist could not confidently rule Brastow’s death a homicide.

Mustard arrested Daniels on site, and the next day attended Brastow’s autopsy, which was conducted by Susan Hogan, a forensic pathologist with the Solano County Coroner’s Office. The detective was adamant that Daniels had murdered Brastow, state bar court records show, theorizing that Daniels had tied up Brastow and shoved a sock down her throat, suffocating her.

Hogan, however, was not convinced.

Brastow’s injuries were not consistent with strangulation, according to Hogan, a veteran pathologist. While Hogan opined the cause of death to be asphyxia, she did not believe there was enough evidence to conclude that it was a homicide. The coroner’s office later ruled the manner of death undetermined, records show.

“What will it take for you to call this a homicide?” Mustard allegedly said as Hogan was concluding the autopsy.

Hogan’s audio notes captured during the autopsy reveal the doctor’s frustration.

“Matt Mustard wants this to be a homicide, and there is no way I could call this at this point and I’m not going to be pushed into it, so he can go kiss my ass,” Hogan stated, according to the state bar court opinion.

The Solano County District Attorney’s Office charged Daniels with murder on Aug. 13, 2012. But without a final autopsy report at the time, and with Hogan’s preliminary finding that the manner of death was undetermined, prosecutors dropped the charge. Mustard was still convinced of his theory, and allegedly continued to pressure Hogan, state bar records show.

In a Jan. 10, 2013 meeting with former Solano County prosecutors Andrew Ganz and Eric Charm, former Vallejo police Capt. James O’Connell and two coroner sheriff’s deputies, Mustard again pressed the case for his sock-down-the-throat theory, according to state bar records. Hogan responded with a detailed scientific rebuttal, state bar records show; she recalled that Mustard and Ganz glared at her throughout the meeting.

But Ganz and Mustard agreed that the case should still move forward, even though it would largely rely on Hogan’s findings, according to state bar records.

“My opinion is that if we do nothing else he gets away with murder and he knows what he did and becomes empowered and another victim of his violence is just a matter of time,” Mustard wrote in a Sept. 16, 2013 email to Ganz, according to state bar records. “I think that we have done cases that have more obstacles than this one and we need to throw it against the wall and see what sticks.”

Ganz and O’Connell did not respond to a request for comment. Hogan could not be reached for comment. District Attorney spokesperson Monica Martinez declined to comment, noting that Ganz was no longer with the agency and Charm did not litigate the case.

On Sept. 23, 2013, Ganz refiled charges against Daniels, puzzling the public defender assigned to the case, records show. In discovery, Ganz did not disclose Hogan’s reservations nor the fact that the January meeting took place. Neither Hogan nor Mustard mentioned the meeting in trial testimony.

Hogan testified during Daniels’ Nov. 25, 2013 preliminary hearing that she planned to retire the following week. But in January 2014 she revealed to the district attorney’s office that she was instead fired in December 2013, partially blaming Ganz. The January meeting and Ganz and Mustard’s issues with Hogan were revealed after Daniels’ attorney subpoenaed her personnel file in January 2014.

A jury found Daniels not guilty on all counts on April 17, 2014 after Judge Daniel J. Healy revealed Ganz’s failure to disclose the meeting with Hogan to the jury. In 2018, the California State Bar filed disciplinary charges against Ganz, a former Solano County Prosecutor of the Year, in connection with the Daniels case. The following year, the State Bar Court found Ganz culpable of four counts of misconduct and suspended his law license for one year, but allowed him to serve two years of probation and a 90-day suspension instead.

Ganz is now a partner at Rains Lucia Stern St. Phalle & Silver, which for years counted the Vallejo Police Officers’ Association as a client. It is unclear whether Mustard was ever disciplined in connection with the case.

‘How do I make it so you look like a monster?’

On March 23, 2015, Vallejo resident Aaron Quinn called Vallejo police to report that his girlfriend, Denise Huskins, had been kidnapped from his Mare Island home in the middle of the night. Quinn told police that multiple individuals had woken the couple up, bound and drugged them, and taken Huskins. Quinn says he was threatened not to call police, and that the invaders had set up a camera to ensure his compliance.

After multiple hours, Quinn finally called Vallejo police. At police headquarters, he was given jail clothes to wear and was taken to an interrogation room. Mustard and other detectives grilled Quinn about the incident for nearly 18 hours, according to court records, during which Mustard repeatedly accused Quinn of murdering Huskins.

“I’m a puzzlemaker. And I put a lot of puzzles together,” Mustard told Quinn during questioning. “So now I get out my puzzle pieces and I start figuring out, okay, how do I make it so you look like a monster?”

Police missed key evidence that could have pointed them to Huskins’ location sooner, Huskins and Quinn subsequently alleged in a lawsuit. Quinn told police that the kidnappers would attempt to contact him, which they twice did. However, police had placed Quinn’s phone on airplane mode while he was being interrogated.

Mustard at one point tried to convince Quinn’s brother, an FBI agent and lawyer, to pressure him to admit to murdering Huskins, the couple’s lawsuit alleged.

Mustard’s theory began to shift after a proof-of-life recording was emailed to the San Francisco Chronicle the next day. In the Netflix documentary, Huskins’ mother said in an interview that Mustard asked for details of her daughter’s dating history, and at one point suggested that women who are survivors of sexual assault often attempt to recreate the experience to relive the “thrill” of it.

Two days after being kidnapped, Huskins turned up alive 400 miles away, wandering her father’s neighborhood in Huntington Beach. This only ramped up false claims against the couple by the Vallejo Police Department. At a press conference on the evening of Huskins’ release, police spokesperson Lt. Kenny Park accused the couple of draining resources from the city.

But Mustard’s theory unraveled when, on Oct. 1, 2015, a grand jury indicted Matthew Muller, a disbarred attorney, for Huskins and Quinn’s home invasion. Muller, a former U.S. Marine and Harvard Law School graduate, was arrested after being identified in connection with investigations in Dublin and Palo Alto over incidents strikingly similar to Huskins’ experience in Vallejo. But Vallejo police did not solve the case: instead, it was the investigative work of then-Dublin police Ofc. Misty Carausu that connected Muller to Huskins’ kidnapping. Carausu, who is now a lieutenant with the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office, did not respond to a request for comment.

In March 2017, a federal judge sentenced Muller to 40 years in federal prison for kidnapping Huskins, and in March 2022, he received another 31 years in state court, to be served concurrently. Muller was given two additional life sentences Friday in connection with two break-ins and attempted sexual assaults in Palo Alto and Mountain View that occurred in 2009.

Quinn and Huskins settled a defamation lawsuit against Vallejo for $2.5 million in 2018. Vallejo police did not publicly apologize for the incident until 2021.

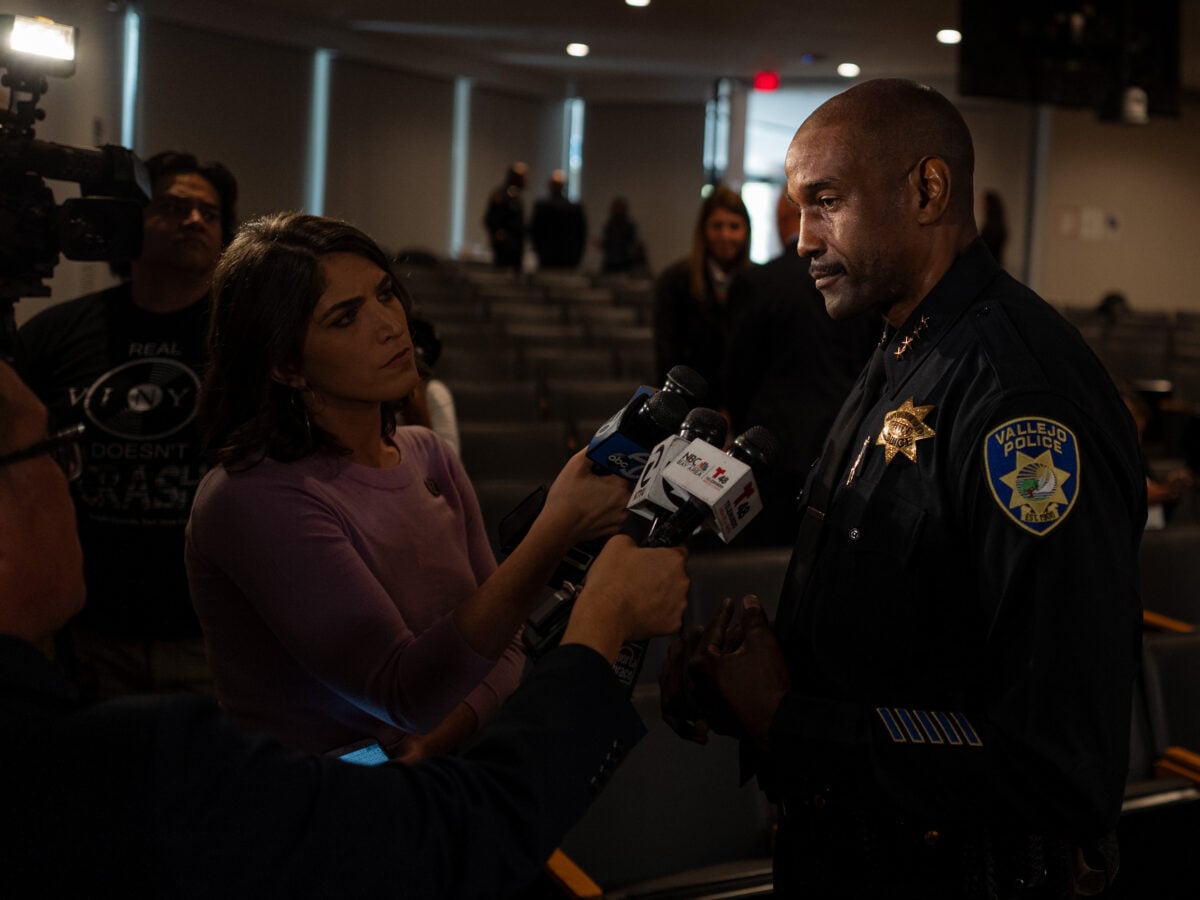

“What happened to Ms. Huskins and Mr. Quinn is horrific and evil,” said then-Vallejo Police Chief Shawny Williams, in a 2021 statement to ABC 7. “Although I was not chief in 2015 when this incident occurred, I would like to extend my deepest apology to Ms. Huskins and Mr. Quinn for how they were treated during this ordeal.”

‘Officer of the Year’

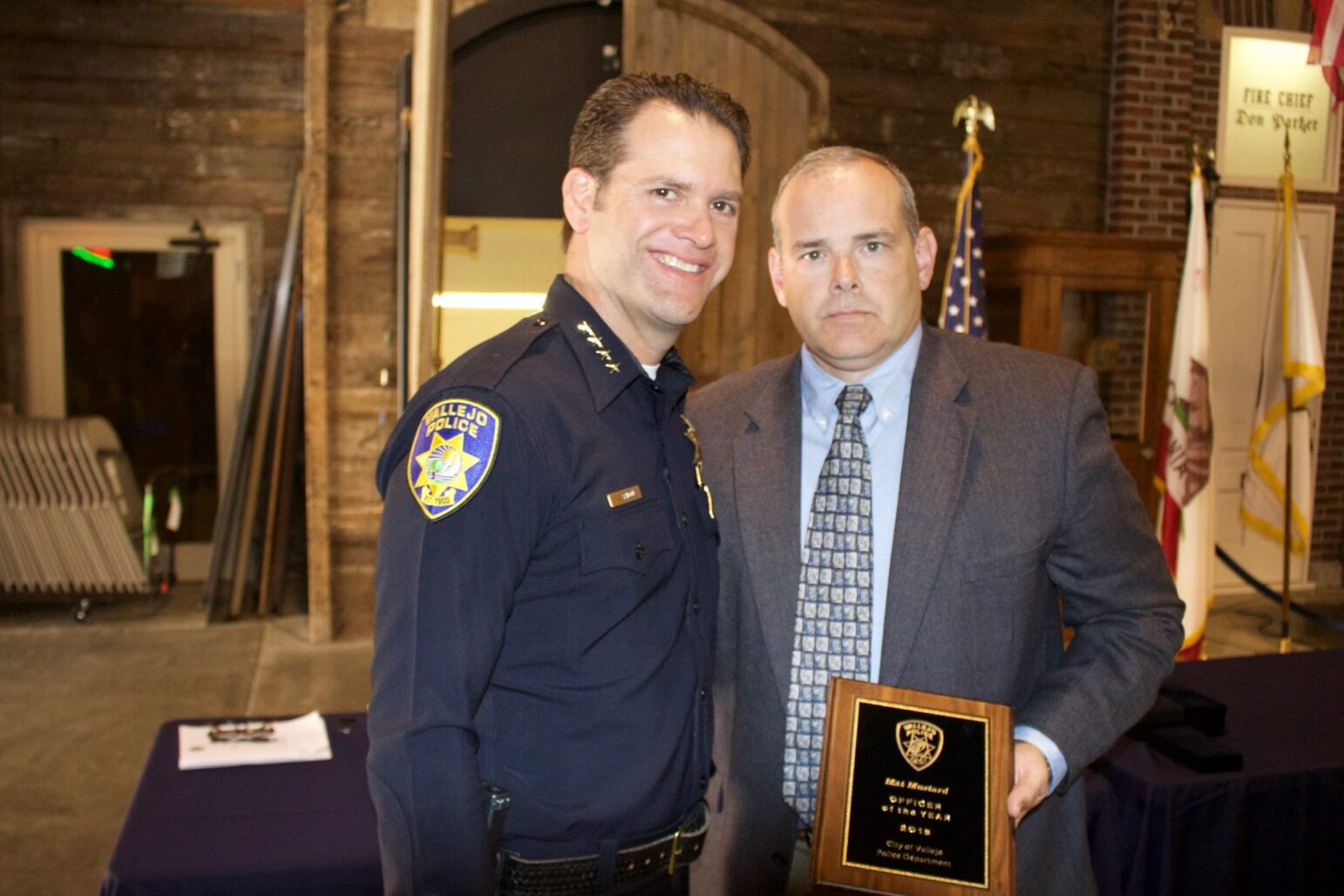

Mustard was never reprimanded for his bungling of the Huskins investigation. Instead, his colleagues presented him with the 2015 Officer of the Year Award. Two years later, he was promoted to sergeant.

But the promotion did not come without its own controversy.

On Dec. 14, 2022, former Vallejo Police Capt. John Whitney testified in a whistleblower lawsuit that former police chief Andrew Bidou lowered promotional exam standards at Mustard’s request. Whitney was fired in 2019 after raising concerns about officers ceremonially bending their badges to commemorate shootings and other alleged misconduct. He settled his lawsuit against the city for $900,000 in 2023.

Whitney declined to comment for this article.

In a deposition in the case, Whitney claimed that Mustard initially failed a written portion of the sergeant promotional exam, and approached Bidou to change the exam — a move that Whitney and former police captain Lee Horton strongly opposed.

Bidou and Horton did not respond to requests for comment.

Whitney testified in a deposition that the changes watered down the exam, particularly by changing the weight of the written portion of the test, and removing a provision requiring a passing score of 70% or higher to advance in the promotion process.

“Several officers in the department came to me and wanted to discuss it. They were upset that the process had been changed and believed that it was changed to benefit Mat Mustard,” Whitney testified.

As a sergeant detective, Mustard’s alleged behavior drew more controversy after a 2020 independent investigation found he made a racist joke on at least one occasion and twice addressed Det. Cpl. Jason Scott, who is Black, as “boy.”

After a power outage in nearby Dixon, Mustard described the town as “dark as Coley’s ass,” according to a confidential report by outside investigator Dorothy Le of the firm Ellis & Makus LLP, which the city of Vallejo hired to investigate Scott’s claims. Witnesses told the investigator the phrase referred to a joke Mustard’s grandfather would tell about the only Black man who lived in an elder relative’s neighborhood; Scott alleged that Mustard looked directly at him as he made the comment. Mustard said “Coley” referred to his grandfather’s black dog, which Le concluded was not credible. The investigator instead determined that the phrase was a “widely known comment about a black person.”

Scott also alleged that Mustard had been tougher on him because he was Black, according to the investigation. In one incident, Mustard reprimanded Scott in front of his colleagues for not finishing a search warrant as instructed, the investigation found. Mustard then barred Scott from eating pizza that Scott brought back for a team of detectives working late until he finished his task. The investigative report found that although Mustard denied Scott pizza and spoke “sternly and angrily” to him, the incident — as well as others alleged by Scott — could not be attributed to racial bias.

From the start of Mustard’s tenure as detective sergeant, there were claims that he had an issue with Scott. When Mustard was promoted he allegedly asked Whitney to move Scott back to patrol, according to Whitney’s deposition in his whistleblower lawsuit.

Whitney testified that he told Mustard to help Scott adjust to his relatively new assignment as a detective, but Mustard allegedly refused, telling him it was not his job. Mustard also told the former captain that he believed Scott was lazy, Whitney alleged.

It is unclear whether Mustard was ever reprimanded in relation to Scott’s allegations. Vallejo police spokesperson Sgt. Rashad Hollis did not respond to requests for comment.

Scott left the Vallejo Police Department in September 2021 after nearly 16 years in the city. He is now a criminal investigator with the Solano County District Attorney’s Office. He declined to comment for this story.

Destruction of evidence

Mustard also initiated the illegal destruction of Vallejo police shooting records in 2021.

On Jan. 8, 2021, amid an ongoing investigation into Vallejo police by the California Department of Justice, Mustard emailed Assistant City Attorney Katelyn Knight regarding five police shooting files he located while “doing research on OIS cases.”

“Before we return, dispose, or destroy any of this Evidence we wanted to clear this with the City Attorney’s Office,” Mustard wrote, copying two other members of the Vallejo police command staff.

“These are all ok to release or destroy per the retention schedule,” Knight responded, despite Open Vallejo’s public records requests for the same files, which had been pending for years.

Mustard was a lead investigator in all of these cases and was at the scene during one of them, according to a review of the case files by Open Vallejo. He also conducted interviews of shooting officers in each case, which means videotapes of his own interviews were destroyed at his initiative. All of the shootings involved at least one officer linked to Vallejo’s badge-bending scandal.

The police department’s then-public records coordinator, Joni Brown, testified in a May 2022 deposition in a public records lawsuit by Open Vallejo that the city did not keep a backup of the destroyed records. But in October 2024, the city released some audiovisual records thought to have been destroyed during the 2021 purge. The disclosed records represent only a fraction of the purged case files, the destruction of which Solano County Superior Court Judge Stephen Gizzi ruled violated state law in May 2023.

The disclosed records included footage of Mustard interviewing former officers Sean Kenney and Dustin Joseph, who mortally wounded Mario Romero in 2012, shooting him 30 times; and Lt. Steve Darden, who shot and killed Mohammed Naas in 2013.

The city has yet to explain how the records resurfaced. A public records request by Open Vallejo for communications relating to their rediscovery was closed earlier this year. In lieu of communication records, the city provided signed affidavits from City Manager Andrew Murray, City Attorney Veronica Nebb and Knight declaring that they did not have anything to turn over. Although the request also sought records from Mustard and Vallejo Police Chief Jason Ta, the city disclosed none, and did not provide affidavits from either officer.

Knight did not respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson for the city of Vallejo declined to comment for this story.

Mustard will earn $182,497.44 annually from his public employee pension, according to a spokesperson for the state retirement agency.

‘Taxpayers will have to pay’

For Quinn, Mustard’s quiet departure is fitting.

He told Open Vallejo in an interview Friday that Mustard never apologized for his conduct in the 2015 kidnapping investigations.

Since the kidnapping, Huskins and Quinn have traveled the country giving speeches at law enforcement events to share their story. Quinn said they want police to learn from their experience to prevent a repeat of what happened to them. Among the changes they have advocated is a shift from outdated interrogation tactics to science-based interview approaches.

“It’s unfortunate taxpayers will have to pay his retirement benefits, as he’s in our personal experience tried to put innocent people away due to his lack of investigative integrity,” Quinn said.