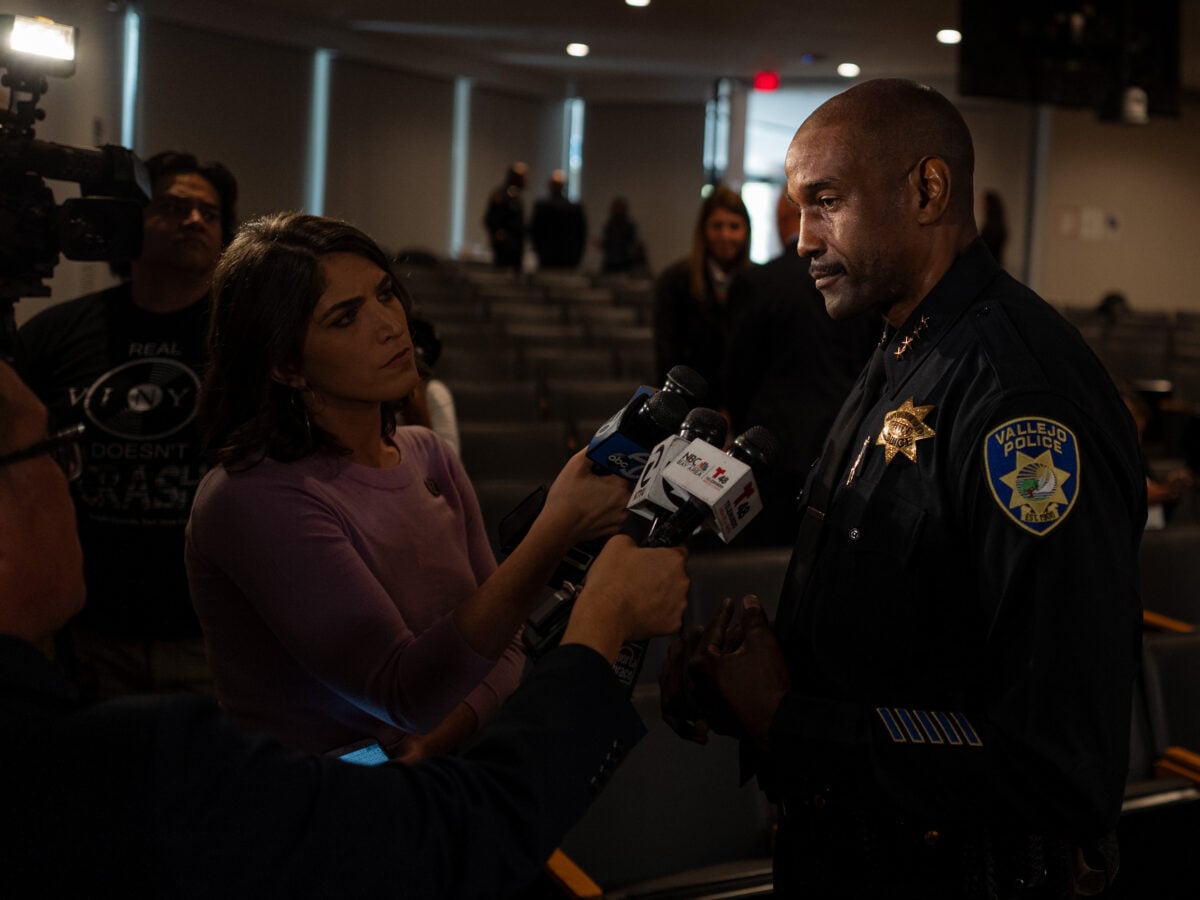

Public remarks by two Vallejo officials about a recent police shooting risk biasing the case and undermining the investigation’s integrity, according to law enforcement oversight experts.

Phillip Balbuena and Richard Hybels, members of the Vallejo Police Department’s Critical Incident Review Board and the city’s Police Oversight and Accountability Commission, respectively, made the comments on Facebook on Sept. 12. In a series of posts, they appeared to state conclusions about the shooting following a short presentation by police at a community town hall the previous evening.

Police played four 911 calls leading up to the shooting, dispatch audio, and body and vehicle camera footage at the community town hall, which Balbuena and Hybels attended. Video of the shooting shows 24-year-old Alexander Schumann walking toward police and aiming what appears to be a firearm before raising his hands and turning away as officers fire at him. Police later discovered that Schumann, who reportedly made statements about wanting to die, was carrying a pellet gun.

Schumann, who survived the shooting, faces several misdemeanors in connection with the incident, after Judge John B. Ellis downgraded a lone felony vandalism charge.

In one post, Balbuena wrote, “While this was technically within the use of force policy, had that been a real firearm, two officers aren’t walking away from that scene.”

In the same comment section, Balbuena said that the city’s unarmed mental and behavioral health team, IHART, was not a viable de-escalation option.

“The fact he already had multiple warrants outstanding meant he was going to be detained regardless of the outcome,” Balbuena wrote.

“Some are forgetting the fact this was a targeted attack by him, and they need to ensure the actual victims safety as well,” Balbeuna wrote on Facebook.

Hybels responded to Balbuena with an observation about the officers’ marksmanship.

“As a veteran I’m surprised what good shots cops tend to be. In the Army I used the .45 and after 25 yards it was pretty hard to get near the bulls eye,” Hybels wrote. “On the other hand the suspect is lucky to be alive cuz they were not aiming for legs etc. for sure.”

Hybels then turned to the shooting itself.

“Cops had no choice in this case as he came from behind the car with gun pointed at them immediately,” he continued.

Balbuena twice declined to speak on the record in phone calls last week. He instead published a statement on Facebook Wednesday in which he stood by his remarks about the shooting. Balbuena wrote that Open Vallejo’s news coverage of his comments “looks to stifle my First Amendment rights” and “antagonize individuals fighting to make this Vallejo better.” (Only the government, or government officials, can violate the First Amendment.)

Balbuena, who also serves on the city’s Planning Commission, then blocked Open Vallejo reporters from viewing his Facebook account, which he routinely uses to comment on both police and planning issues.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled last year that public officials who use personal social media accounts to post on topics relating to their work can be held liable for violating the First Amendment when they block critics while speaking on behalf of the government. In 2020, Open Vallejo and the Electronic Frontier Foundation sent a legal demand to the city of Vallejo that officials stop blocking members of the public on social media, prompting the city to formulate a new social media policy.

Open Vallejo reached out to all seven members of the POAC, who either declined to comment or did not respond. But in a Sept. 26 Facebook post, Hybels responded to Balbeuna’s statement from two days earlier.

“As always, very well said Phillip,” Hybels wrote.

Vallejo police policy typically prohibits officers from publicly discussing ongoing investigations. However, the oversight boards on which Balbuena and Hybels serve differ on the extent to which such discussion is allowed. The CIRB, for example, does not appear to include an explicit prohibition, though police policies relating to confidentiality likely apply; the POAC ordinance includes strict rules regarding the sharing of confidential information.

Vallejo Mayor Andrea Sorce emailed City Manager Andrew Murray and Police Chief Jason Ta about Balbuena’s comments on Sept. 12, public records show.

“I am deeply, deeply concerned by this and cannot imagine that this is within policy for the CIRB,” Sorce wrote. “My understanding is that members are bound by confidentiality, and at the very least this behavior should result in immediate removal from the board and replacement with a different civilian member for the remainder of this incident’s review process, in order to restore integrity.”

Neither Murray nor Ta responded to a request for comment for this article. Open Vallejo also contacted the city attorney’s office and each member of the Vallejo City Council, as well as spokespeople for the city and the police department. With the exception of the mayor, who is also a member of the city council, none responded.

Sorce reiterated her concerns in a statement to Open Vallejo Friday.

“I immediately reached out to the City Manager and Police Chief and asked what steps will be taken to remediate and ensure the investigation and review remains independent,” Sorce wrote. “I have not yet received a response to that question.”

‘Wildly inappropriate’

Police oversight experts told Open Vallejo that publicly discussing open cases risks damaging the integrity of the oversight process.

“These are ongoing investigations, and one of the comments indicates that the individual has already concluded that the officers had no choice. Another one seems that they are defending the officers, and another seems to be kind of making light of the shooting,” said Georgetown Law Center professor Christy E. Lopez, a former deputy chief in the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice. “None of those things should be happening.”

In his Sept. 24 statement, Balbuena characterized his remarks about the shooting as an attempt to correct unspecified “misleading comments” in the press.

“I believe people should have relevant unbiased information to garner their own conclusions,” Balbuena wrote.

Vallejo police policy empowers the chief to select CIRB members following an internal nomination process. The board, which is almost entirely composed of law enforcement personnel, must also include at least one community member selected through an “open process, as established by the chief,” a result of state-mandated reforms.

The Vallejo City Council has authority over the oversight and accountability board, whose members are selected through public interviews, nomination by council members and confirmation by a vote of the council.

While comments by individual members of oversight groups may not reflect the opinions of the various other stakeholders involved in the oversight process, they can complicate the work, said Cameron McEllhiney, executive director of the National Association of Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement.

“When you are doing the work of civilian oversight, you really can’t be there to be for one side or the other,” McEllhiney told Open Vallejo. “You really need to be there for the process so that you can carry out the mandate that was given to the civilian oversight entity, and be able to do the work in a way that’s seen as effective and legitimate.”

According to Seth Stoughton, a law professor at the University of South Carolina and a former police officer, integrity is central to the civilian oversight process.

“In a review of an officer-involved shooting, we need two things,” Stoughton said. “It needs to be accurate. That is, it needs to come to the right result, but it also needs to be legitimate. It needs to be viewed as trustworthy by the public.”

Setting aside one’s personal views is particularly important for ensuring the public has faith in the investigative processes, according to Stoughton.

“There is a cognitive bias that comes into play,” Stoughton said. “The way that I as an investigator ask the questions, the way that I go about doing that investigation, can change the results of that investigation.”

Balbuena wrote in the Facebook post that when offered the CIRB community member appointment, he alerted officials that he would remain vocal on social media. He added that he made this a condition of stepping down from the city’s Surveillance Advisory Board to take the CIRB position.

Stoughton, who served as an expert witness for the prosecution in the 2021 trial of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, told Open Vallejo that he is in favor of sharing information in the course of a complicated investigative process, with exceptions.

“One of the things that should not be shared until all of the facts have been gathered and all of the questions that can be answered have been answered, is the ultimate conclusion of whether or not the action was appropriate or not,” Stoughton said.

The POAC is currently inactive pending an ongoing labor dispute with the Vallejo Police Officers’ Association and delayed mandatory training by the city attorney’s office, although the board would likely review the Aug. 29 incident if it were actively functioning.

Though it is unclear when the commission will begin its work, “there is no statute of limitations on public opinion,” Stoughton said.

“It’s important to maintain your objectivity until the end of the case,” Stoughton told Open Vallejo. “Evidence that can come in at the very end of the case could change your mind.”

While the experts Open Vallejo spoke with agreed that Balbuena’s and Hybels’ comments were improper, they differed on the remedy.

Stoughton told Open Vallejo that Hybels’ and Balbuena’s comments merit their recusal from the Schumann shooting investigation. He said the city should be concerned about the appearance of bias or impropriety, regardless of whether the comments compromise the investigation.

“Think about what would happen if a judge was overseeing a case, or was anticipating overseeing a case and was making public comments on Facebook about how that case would come out or whether he thought it was a good case or not,” Stoughton said. “It would be wildly inappropriate. This is not really that different.”

Lopez said that while it may seem obvious that discussing ongoing investigations is inappropriate, agencies should have clear written rules for officials serving on oversight bodies, with accountability mechanisms up to and including removal to address violations.

McEllhiney also noted the importance of setting clear expectations.

“There are many aspects of our life that if it isn’t a rule, then we don’t have to follow it,” she said.

Stoughton said agencies should consider screening individuals being considered for oversight boards, similar to the process potential jurors go through, and provide in-depth training on investigative best practices. It remains unclear when or how Balbuena was appointed, or whether Ta considered other individuals for the appointment.

“While people certainly will continue to have their own personal opinions, most people, I think, do a fairly good job of living up to the expectations of their role when they are aware of those expectations,” Stoughton said.

The people’s business

Oversight public officials who comment about ongoing cases face risks beyond the investigative process.

Because the POAC is a creation of the city council, it is subject to the Ralph M. Brown Act, a state law governing how local legislative bodies conduct public meetings. The law does not prohibit individual commissioners from commenting on public business, according to David Loy, legal director at the First Amendment Coalition, a transparency advocacy organization. But if the majority of a legislative body wants to discuss a topic over which they have jurisdiction, the body must ensure public notice and participation.

Although the POAC has not officially conducted any business, Loy told Open Vallejo that it is still subject to the Brown Act, even if the commission’s work is paused.

Hybels’ comments appeared in the Facebook group “Vallejo City Politics,” which includes five out of seven POAC commissioners as members. However, Loy said this does not constitute a Brown Act violation because there was not a majority of POAC officials actively engaging in the same discussion thread.

In addition to the notice and participation requirements for public meetings, in 2020 the California Legislature amended the Brown Act to prohibit members of a legislative body from responding directly to “any communication” on social media by another member of the body on a topic within their jurisdiction.

Although the POAC is regulated by the Brown Act, the CIRB is not, meaning the exchange between Hybels and Balbuena did not violate the law, according to Loy.

Both the POAC and community member seats on the CIRB are relatively recent changes adopted by the city in response to mandates from the California Department of Justice.

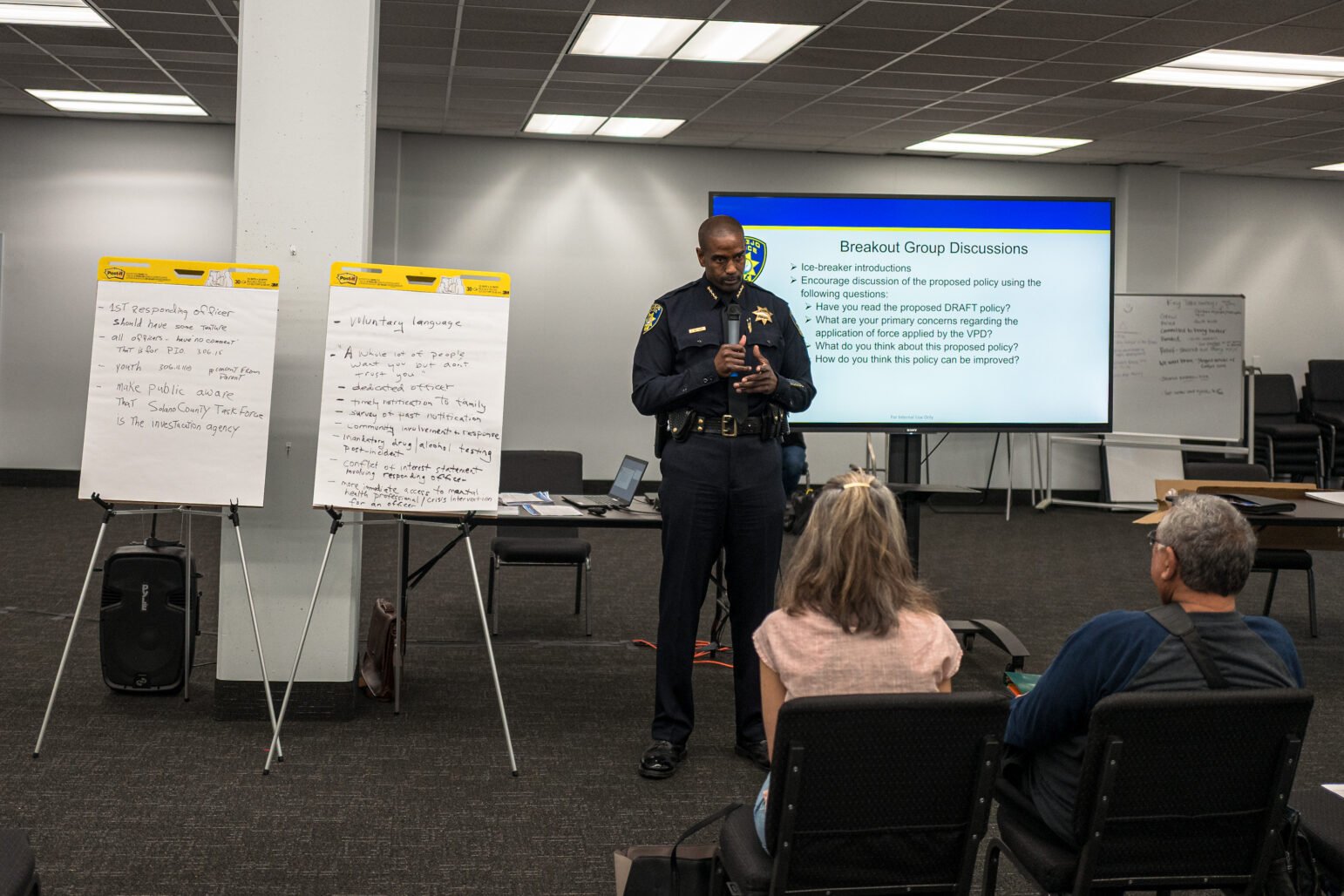

In early 2020, state DOJ began investigating the city of Vallejo over the “number and nature” of shootings by officers. In June of that year, a Vallejo detective with three prior shootings killed Sean Monterrosa; days later, the city entered into a collaborative agreement with the state attorney general “to modernize and reform VPD’s policies and practices and increase public trust.”

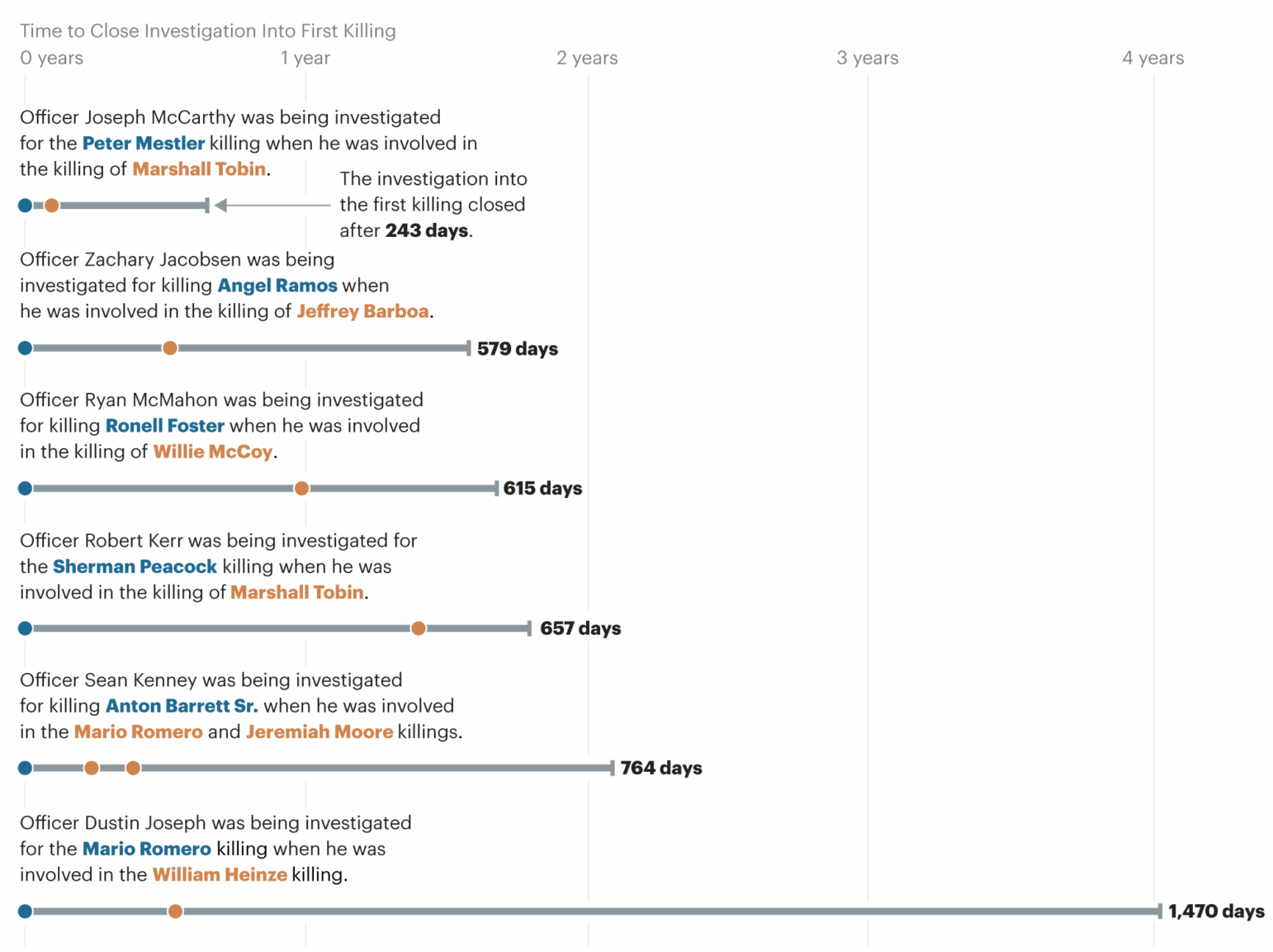

A 2022 investigation by Open Vallejo and ProPublica found that over the previous decade, the Vallejo Police Department’s flawed handling of fatal police shootings allowed six officers to use deadly force again before their first cases were decided.

The collaborative effort ultimately stalled. California Attorney General Rob Bonta appeared to lose patience, and sued the city in October 2023. The parties entered into a binding reform agreement last April, which requires enhancing community engagement related to the CIRB and establishing civilian oversight.

Vallejo passed an independent oversight ordinance establishing the POAC and an independent police auditor in December 2022. Within weeks, the Vallejo Police Officers’ Association filed an unfair labor practice charge with the state, claiming that the city had not met with the union before implementing the policy.

Since January 2023, the POAC has not begun its work because its members have yet to complete a series of city attorney-led trainings required by the ordinance. The ordinance requires the city attorney’s office to provide the training within nine months of the commissioners’ appointment, a deadline that has expired for all but one commissioner.

The POAC has already lost a notable name in police reform. Mike Nisperos, a former prosecutor and a key figure in the creation of Oakland’s Police Commission, stepped down in March as he accused the city attorney’s office of stalling the commission’s work. The city council has already had to reappoint another commissioner, whose term expired while the commission was awaiting training.

It has been more than four months since the last POAC training, and no future public meetings are currently scheduled. The CIRB is not required to hold public meetings, and it is currently unclear when it will issue its final report on the Schumann incident.

“It’s critical that all processes following an officer-involved shooting are followed and that investigations are independent,” Sorce told Open Vallejo. “We are working to build trust with the community after a troubled past, and in order to do so we must hold ourselves to exceptionally high standards of integrity.”