On Feb. 9, 2019, six Vallejo police officers surrounded 20-year-old Willie McCoy, who had fallen asleep in his car with a gun allegedly in his lap. When McCoy stirred, the officers screamed commands at him for three seconds, then fired 55 jacketed hollow-point bullets in unison. Struck 38 times, McCoy died at the scene.

At first, the city of Vallejo refused to disclose body camera footage of the shooting, in violation of state law. Then, a councilmember whom the police union had endorsed disclosed that he watched the video, which Open Vallejo used to compel its disclosure using a 1970s-era appellate court decision involving the Black Panther Party.

The killing drew worldwide condemnation. Articles about Open Vallejo’s investigation appeared in publications on several continents and in multiple languages. In the Guardian, a British newspaper, American former federal prosecutor Paul Butler observed, “The response by the Vallejo police seems more like an ambush than legitimate law enforcement activity.”

Closer to home, one Vallejo police officer told Open Vallejo the shooting resembled “an execution.” That officer spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear for their safety.

Soon after, I received a disturbing tip: Vallejo police were bending the points of their star-shaped badges to mark each on-duty killing — including McCoy’s.

The investigation took nine months to produce. I started by collecting and analyzing photographs of badges from the city’s website, the department’s social media accounts, and other open-source repositories. When the city refused to disclose official portraits of officers wearing their badges, I went out and made my own.

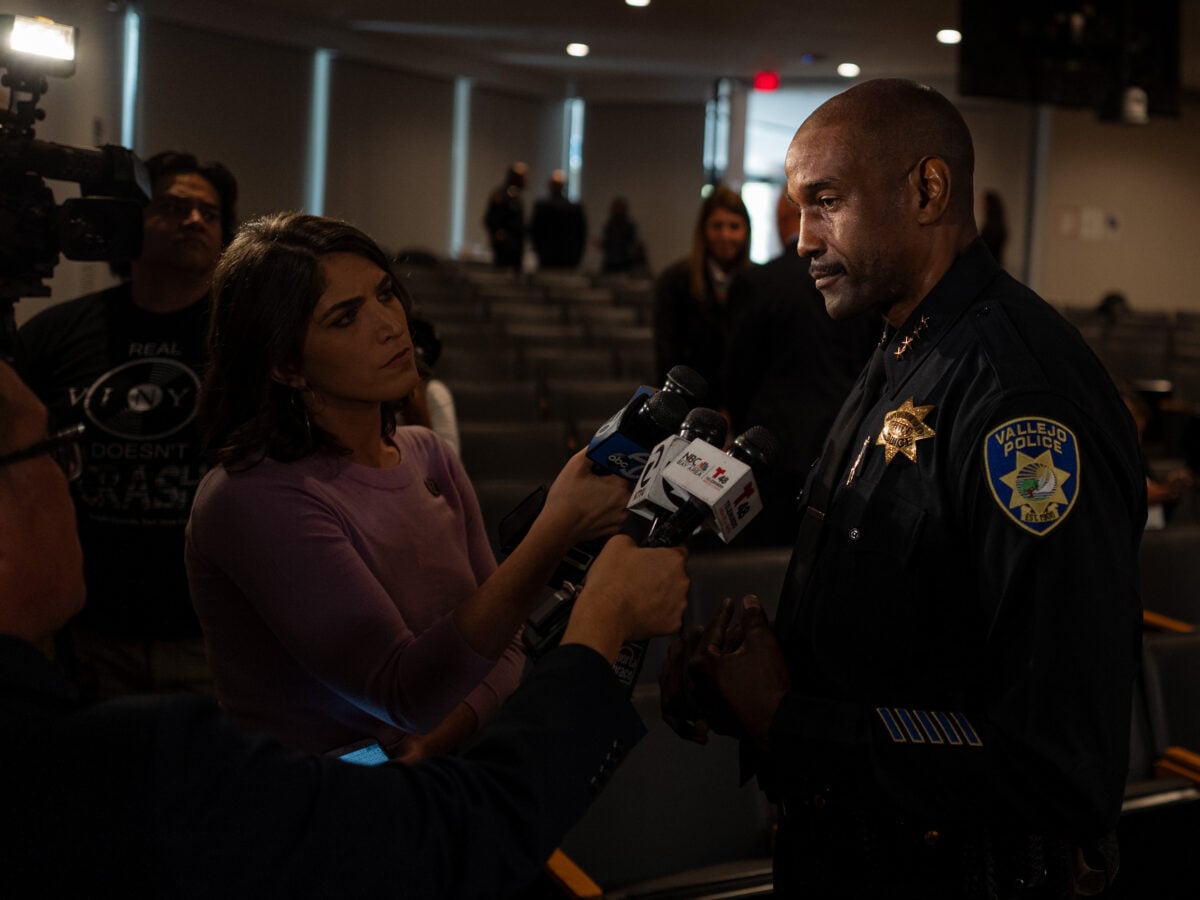

In 2019, Vallejo hired Shawny Williams, the first Black police chief in the department’s more than 100-year history. Police officers and community members packed the city council chambers for his historic swearing-in ceremony in November of that year.

Most Vallejo officers wear utility uniforms bearing an embroidered patch while on patrol. But the gathering meant that many of those present were in their formal uniforms, and thus wearing their metal badges. I photographed as many badges up close as I could.

One of those photographs became the story’s main image. And when I compared the detailed pictures to others I had gathered, they revealed that the first bend is often applied at the 4 o’clock tip of an officer’s seven-point star — a near-algorithmic way of assessing what had begun as little more than a macabre rumor.

Over time, I began to build mutual trust with confidential sources within and outside the city government. To test their claims and understand the scope of the tradition, Open Vallejo built a first-of-its-kind database of every known Vallejo police shooting and killing since 2000, which we later made public under a Creative Commons license. It remains the most comprehensive account of the department’s critical incidents from any source, public or private.

Over months, the photographs, human sourcing, and other evidence lined up. As our publication date neared, I began receiving anonymous, targeted threats. Although the person behind the threats used anonymizing technologies, they did so clumsily, and I soon felt I had enough to identify them.

I gathered up the available digital evidence about the author and turned it over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation so they could open a criminal civil rights investigation. It was a strange experience, as our newsroom jealously guards its independence, and we do not work with law enforcement. But we also do not take threats to press freedom lightly.

The threats stopped, though not before the author — who was never believed to be a member of the badge-bending clique — provided the first real evidence of the intent behind the ritual. He became, for all intents and purposes, a snitch.

Open Vallejo launched on July 28, 2020, with the badge-bending investigation as our top story. The city manager initially denied the report, then quickly backtracked. The mayor, a former police sergeant, confirmed it. A former Vallejo police chief called it “a figment of someone’s imagination.” Days later, Williams, the new police chief, announced a third-party investigation.

The story, which won several national journalism honors, is now impacting cases in both state and federal courts. Civil rights lawyers point to badge-bending to argue the police department should be placed under federal oversight. At the same time, criminal defense attorneys have used it to impeach the statements of alleged participants in the tradition.

Civil rights settlements involving Vallejo police have skyrocketed into the millions of dollars, as have settlements paid out to former police officers and other city officials who filed whistleblower actions.

The California Department of Justice, which launched a review of the department in 2020 due to the “number and nature” of killings by Vallejo police, last year forced the city into a formal settlement agreement. And last month, the California Court of Appeal ordered the release of the city’s investigation into badge-bending in response to a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California with amicus support from Open Vallejo, which the city is now seeking to appeal.

Open Vallejo research shows that from 2000 to 2020, Vallejo police engaged in a shooting once every four months, on average; 30 people have died. (These deaths do not include a man who allegedly committed suicide during a police shootout and five violent deaths in police custody, which officials spuriously ruled accidents.)

The most recent killing by Vallejo police occurred a week after George Floyd’s murder, and less than two months before Open Vallejo published its badge-bending investigation.

Vallejo police have not killed anyone since — now more than five years ago.

Correlation is not causation, and the families of those who died have long been the most eloquent and insistent voices for transparency. But the possibility that our work has contributed to the relative peace, however small, is reason enough for it to continue.