The Vallejo City Council last week appointed the first members to the city’s inaugural police commission, capping a years-long effort to impose community oversight on a police department known nationally for its high rate of lethal violence.

The volunteer Police Oversight and Accountability Commission will review investigative reports into serious misconduct by officers, collect complaints from the public, and give recommendations on department policy, investigations, and discipline.

Its creation stems from more than a decade of activism and organizing by community members, including Kris Kelley, whose brother Mario Romero was killed in 2012 by two Vallejo police officers. But after experiencing the city’s broken promises for years, Kelley said, this does not feel like a moment for celebration.

“To me, it just feels like the City of Vallejo is consistently building on a rotten core,” she said. “It’s too little. It’s too late.”

The establishment of the commission, which is comprised of seven members and one alternate, only partially fulfills Vallejo’s three-pronged approach to police accountability outlined in a December 2022 ordinance.

The city has stalled on another piece of the oversight plan — the creation of an Independent Police Auditor’s office — amid ongoing negotiations with the Vallejo Police Officers’ Association. The ordinance grants the auditor more authority than the oversight board, including access to serious incidents and interviews with officers and witnesses. In 2021, the union hindered a similar effort by sending a cease-and-desist letter demanding the city refrain from hiring the OIR Group as an interim police auditor.

Now, city officials have released a Request for Proposals for the auditor position in preparation to move forward, said Christina Lee, public information officer for the city. The meet-and-confer process is close to complete, she said, without elaborating on a timeframe.

Union president Lt. Michael Nichelini did not respond to a request for comment.

Last Tuesday, city councilmembers appointed to the commission the following Vallejo residents: Mike Nisperos from District 1, Cameron Clark from District 2, Richard Hybels from District 3, Renee Sykes from District 4, Derek Roy from District 5, John Lewis from District 6, at-large member Naomi Yun, and alternate member Melvin Jones. Members have staggered term limits from one to four years.

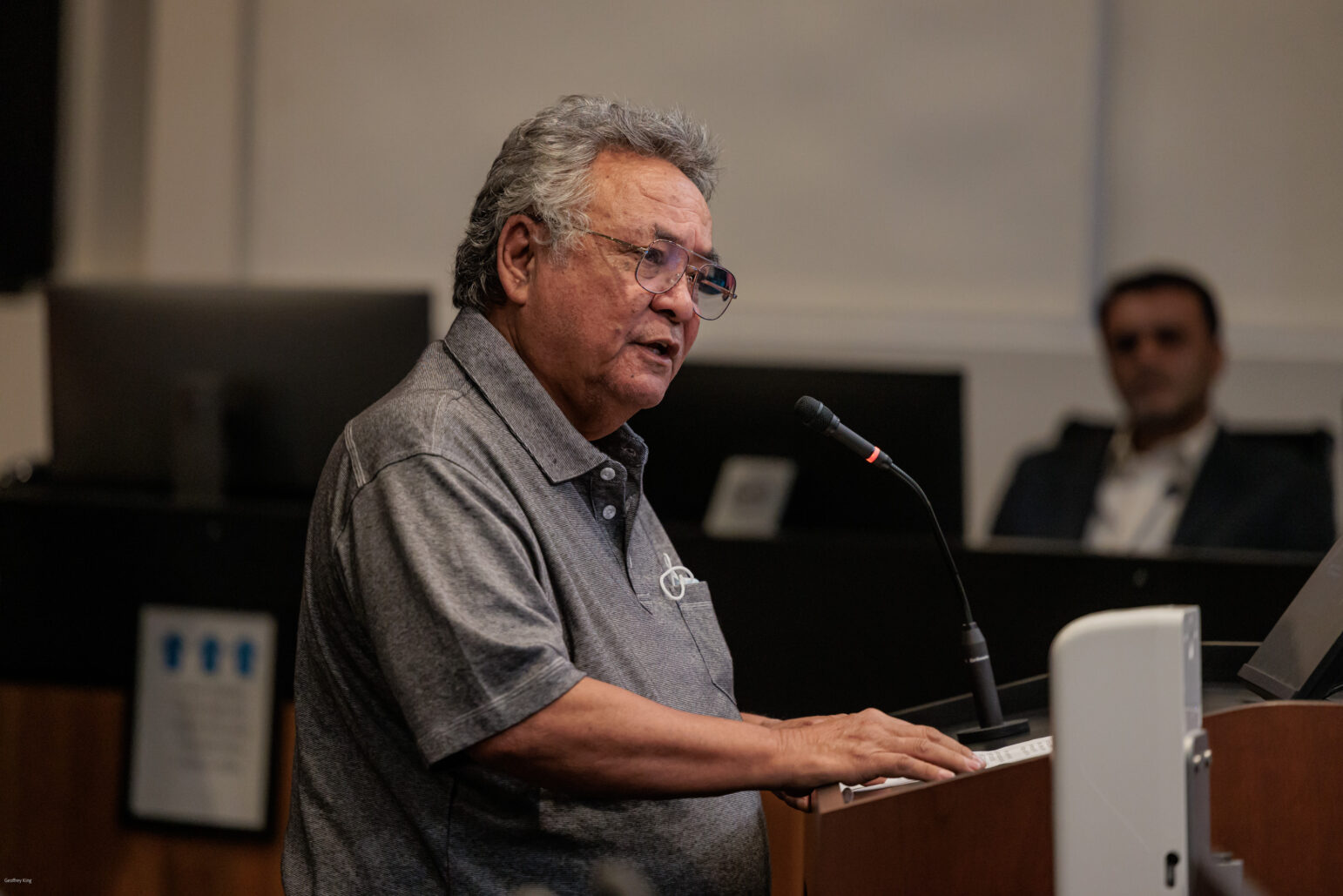

Four appointees have served on other Vallejo advisory boards and commissions and several members have experience working in government. Yun, now a paralegal in San Ramon, worked in the Vallejo City Attorney’s Office as a legal secretary from 2017 to 2019, according to Transparent California. Sykes worked for nearly three decades as a civilian community liaison at the Oakland Police Department. Nisperos, now retired from a legal career that included serving as the Chief Trial Counsel for the State Bar of California, has held several roles in the past two decades on the Oakland Police Commission and its civilian investigative arm.

The city is now conducting background checks on each member, Lee said. The ordinance disqualifies from serving on the commission anyone who works for Vallejo or its police department, serves as a peace officer in any jurisdiction, or is involved in legal proceedings against the city, as well as immediate family members of anyone in those positions.

‘Pretty robust’ oversight

Although more than a year has elapsed since the city council passed the ordinance, the commission cannot immediately begin work — and it may be months before they do so.

That is because, according to the ordinance, the city must first provide and fund roughly 40 hours of training on confidentiality, public records law, Vallejo’s municipal code, and the California Peace Officer Bill of Rights. Committee members must also participate in a police ride-along. The city manager, police chief, and city attorney will help schedule and facilitate the training, which must be completed by November, according to the ordinance.

The ordinance empowers commissioners to review all independent and Internal Affairs investigative reports and supporting evidence related to police shootings, use-of-force incidents resulting in death or great bodily injury, in-custody deaths, and allegations of sexual assault, dishonesty, bias, discrimination, and threats. The commission can subpoena records if the police department fails to provide requested items within a month.

The commission will then provide recommendations to the police chief and the city manager, noting whether members agree or disagree with a report’s findings and conclusions. Commissioners can recommend disciplinary action and further investigation into an incident, according to the ordinance, although those decisions ultimately rest with the police chief.

The authority of Vallejo’s commission is “pretty robust, compared to a lot of places,” said Jerry Threet, a former director of the Independent Office of Law Enforcement Review and Outreach in Sonoma County.

An earlier version of the ordinance, however, would have equipped the group with powers similar to those in Oakland. The East Bay city’s commission is among the strongest in the country, said Nisperos, a new Vallejo commissioner who previously sat on Oakland’s oversight board.

Common Ground, an organization that Vallejo enlisted to help research oversight models, three years ago drafted the more robust ordinance, which granted commissioners the power to remove a police chief with just five votes. It also charged commissioners with preparing a list of four candidates from which the City Manager could select a new chief. But city officials narrowed the oversight board’s powers, stripping it of those functions, while finalizing the ordinance, Nisperos said.

Aside from reviewing investigations and recommending policy, the commission will receive written complaints from the public about Vallejo police officer misconduct and forward them to the police department. The public can submit complaints online, including anonymously, as soon as the board begins its duties.

People may be hesitant to bring their concerns about officer misconduct directly to Vallejo police because “there’s no faith that anything will be done with them,” Nisperos said.

He hopes the commission will give people more confidence in the discipline system and provide an ongoing forum for the community to discuss police matters and influence policy decisions with their testimony.

“There will be more active engagement within the community on issues related to policing than there has ever been,” Nisperos said.

‘They have their work cut out for them’

The creation of a civilian oversight agency alone is not enough to ensure a department’s policing is truly responsive and constitutional, said Threet, the founder of Sonoma County’s oversight agency.

“Oversight is essential but it’s not nearly as important as the leadership of the department,” he said.

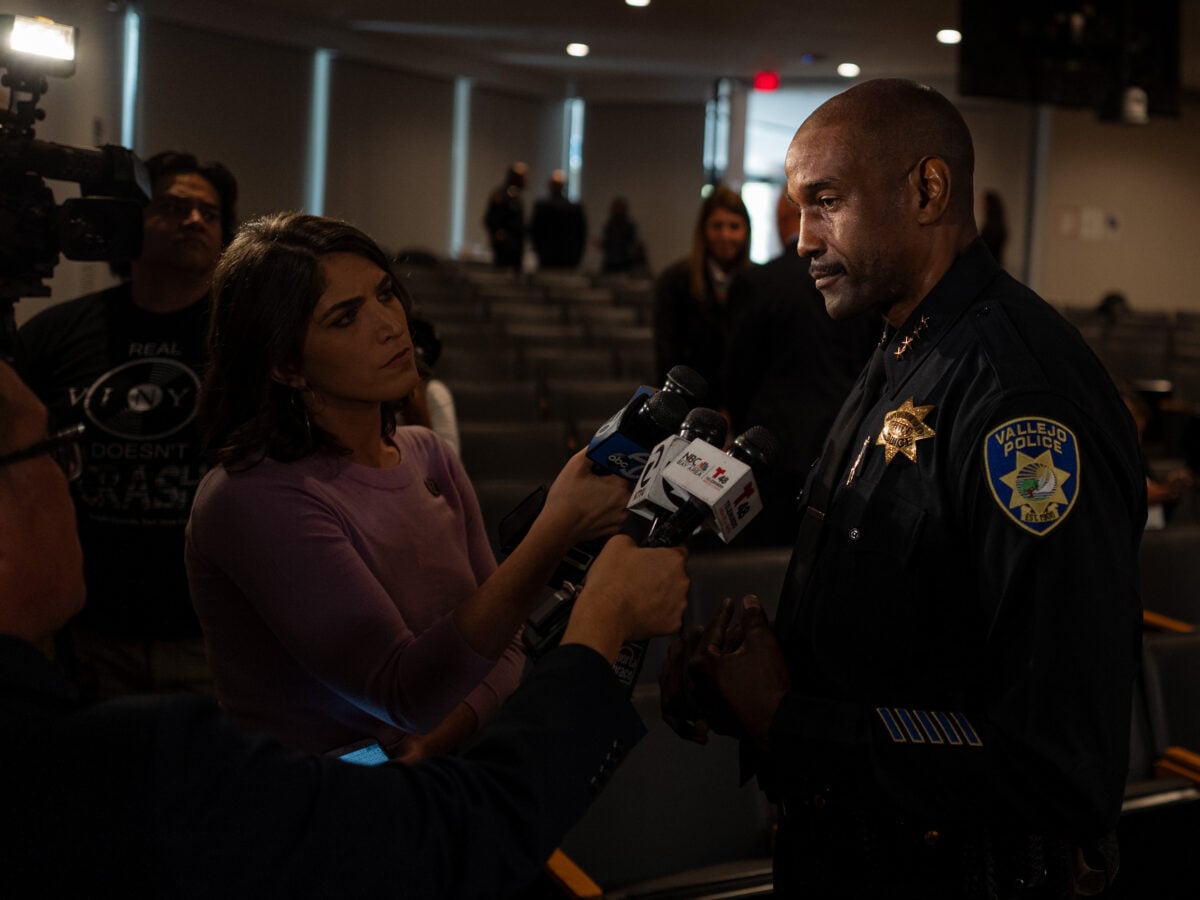

Interim Police Chief Jason Ta, a former Vallejo deputy chief, stepped into his current role after Police Chief Shawny Williams abruptly resigned in November 2022. Earlier that year, Ta allegedly arrived impaired to a homicide scene, according to an internal memo written by a former police captain. Shortly after his promotion to chief, Ta canceled the department’s contract with Truleo, a technology company that helps departments analyze body camera footage, under pressure from the police union.

Last year, Attorney General Rob Bonta appeared to express doubt about Ta’s ability to collaborate with the state on reform efforts that began under his predecessor.

Bonta is now seeking a consent decree that would force Vallejo’s police department to implement sweeping reforms, many of which it failed to achieve during a three-year collaborative agreement with the California Department of Justice that ended last June.

The state agency first announced plans to intervene in Vallejo three days after Det. Jarrett Tonn fatally shot 22-year-old Sean Monterrosa in a Walgreens parking lot on June 2, 2020.

Monterrosa is among dozens of people killed in the past two decades by a police force in which some officers commemorated fatal shootings by bending the points of their badges for each civilian they killed. Tonn, whose termination for killing Monterrosa was overturned last year, is back on Vallejo’s streets as a homicide detective, which has sparked concern among activists and other community members.

Officers implicated in the badge-bending scandal have been awarded and promoted, including Sanjay Ramrakha, whose alleged involvement in the ritual was revealed in court testimony. He has been promoted to Captain effective this month, Open Vallejo has learned.

Neither Tonn nor Ramrakha responded to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, as the department struggles with short staffing, the interim chief’s future with the department remains uncertain. Ta nearly left Vallejo last month to lead the Salinas Police Department before the offer abruptly fell through. Vallejo only recently began its search for a permanent police chief, more than a year after Williams’ resignation. With City Manager Michael Malone set to retire next month, it remains unclear who will step into the position and play a key role in choosing the city’s next chief.

Amid the leadership uncertainty, Threet questioned whether Vallejo’s police department will support the oversight body given the organization’s history of violence and opacity.

“I think they have their work cut out for them,” he said about Vallejo’s oversight board. “It’s going to be a challenging thing, I think, to make the transition to a different kind of department.”

‘A source of frustration’

Civilian oversight of law enforcement agencies has become more common over the past decade, according to the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement, a nonprofit that advocates for more police transparency and accountability.

There were 166 such groups as of 2019 with varying structures and levels of authority, according to the organization, which notes that “no two oversight agencies are identical.”

Berkeley and San Francisco were among the early adopters of police oversight, with their respective agencies established in 1973 and 1982. Other Bay Area jurisdictions have since created various forms of civilian oversight, including Richmond, Santa Rosa, and San Jose. The model is also spreading to smaller cities; earlier this month, Antioch created a new police oversight commission on the heels of a scandal that resulted in federal charges against numerous officers.

Like Vallejo, the police chief in Berkeley has the final say on decisions related to policy and officer discipline, said Hansel Alejandro Aguilar, director of police accountability for that city.

“That has been a source of frustration at times when board members engage in this important policy review work and the recommendations aren’t adopted,” he said.

For example, Aguilar said, Berkeley police recently purchased automated license plate readers despite a lack of support from the advisory board. Still, police and elected officials modified the proposal based on some board suggestions, he said.

For John “Chip” Moore, serving as chairman of Berkeley’s Police Accountability Board is challenging because it requires working with police officers, elected officials, and community members.

“Not all stakeholders are on the same page,” he said. “Trying to get institutions to give up power, whether real or perceived, whether it’s implicit or explicit — nobody wants to lose, nobody wants to feel like they’ve been usurped or not valued.”

As the broader Bay Area reimagines police work, Moore said he hopes Vallejo’s oversight board asks challenging questions about what good policing looks like and how to make every member of the community feel safe, especially people of color.

“Good policing takes work,” he said. “And oversight takes even more.”