In 2020, concerns over the “number and nature” of police shootings in Vallejo prompted the California Department of Justice to launch a three-year collaborative effort with the city to reform its police force.

The Vallejo Police Department vowed to implement 45 reforms, but more than two years into the agreement, Open Vallejo and ProPublica revealed that it had complied with just two. Last month, weeks before the end of the agreement, the department claimed to be compliant with eight reforms.

That was not enough for the state DOJ.

Last week, the attorney general’s office announced it was seeking a “new phase of oversight” of the department in the form of a court-ordered settlement agreement, according to reporting by the Vallejo Times-Herald.

“The indication by Cal DOJ that they intend to escalate to court supervision suggests their discontent with the efforts by VPD,” said Avi Frey, deputy director of the Criminal Justice Program at the ACLU of Northern California.

But what will that mean for the city of Vallejo — and how might it differ from the collaborative approach of the past three years? The state DOJ did not explicitly say, and declined to comment for this story.

So, Open Vallejo asked five police oversight and criminal justice experts to find out.

From collaborative to compelled

Sometimes referred to as consent decrees, court-ordered settlement agreements are contracts overseen by a judge and agreed upon by opposing parties — here, the California DOJ and Vallejo. In the context of police oversight, the agreements contain sets of rules for law enforcement agencies to implement reforms.

“What they fundamentally come down to is an agreement between the party that’s bringing the litigation and the party that’s the defendant,” said Joe Brann, a co-monitor of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department and the founding director of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

But before a settlement agreement can be endorsed by the court, the state DOJ has to make claims of wrongdoing. That means California Attorney General Rob Bonta is likely to file a lawsuit against the city.

“Prior to seeking court involvement in the matter, the DOJ (state or federal) would want to make certain they have sufficient evidence to support any allegations of a pattern and practice of persistent misconduct such as excessive force, biased policing or other constitutional violations,” Brann wrote in an email to Open Vallejo.

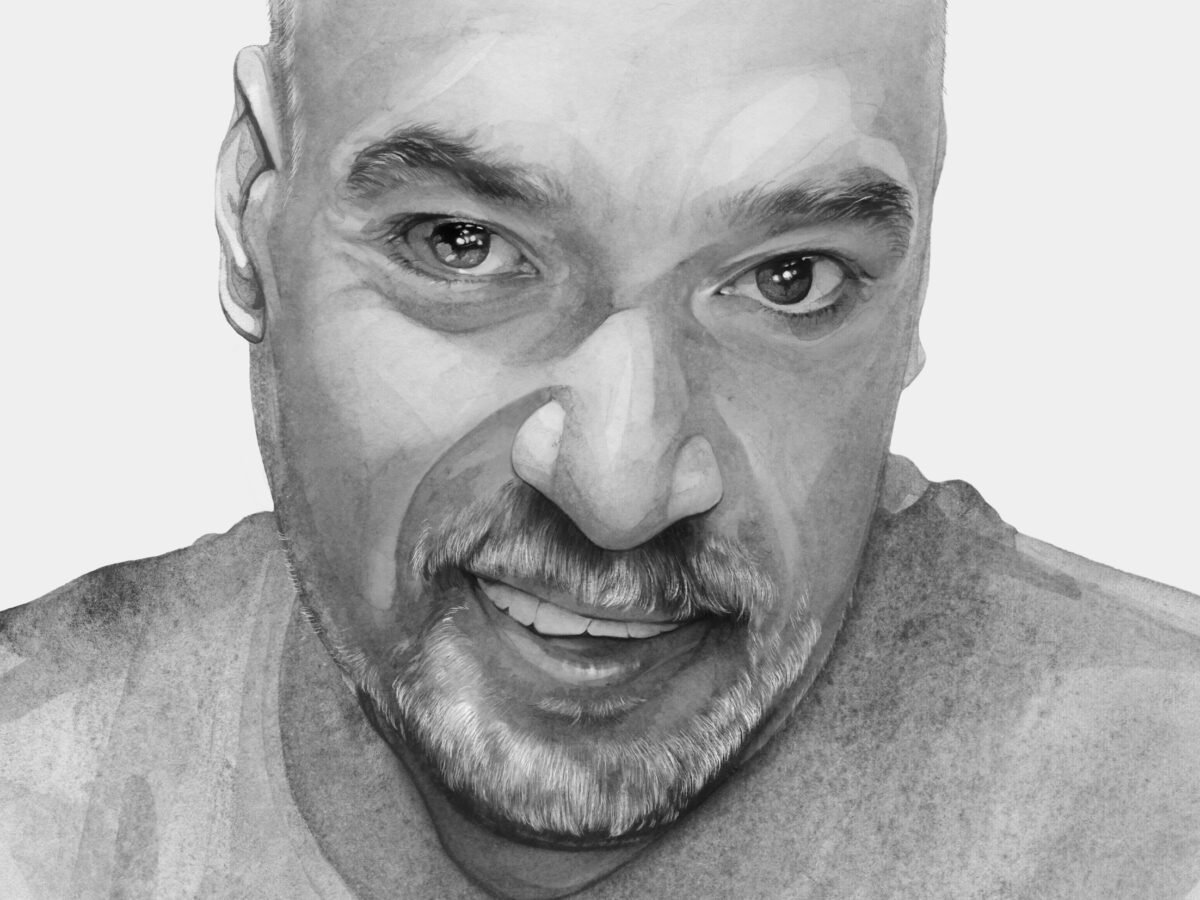

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

California Attorney General Rob Bonta speaks at a press conference announcing an investigation into the Antioch Police Department on May 10, 2023 in Oakland, Calif. In response to a question from Open Vallejo, Bonta said that a civil rights investigation into Vallejo police was “on the table.” Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoOnce the state DOJ has made claims of wrongdoing against the city, the parties can file a joint settlement agreement meant to address those alleged violations, which the court has to approve. The city might not have to agree that it did anything wrong, however.

“Usually, what the defendant will say is, ‘We don’t admit that we actually did any of these things, but we will make all these changes the government wants us to make’,” said Christy E. Lopez, a professor at the Georgetown University Law Center and a former deputy chief in the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The terms of the agreement will be the subject of negotiations between state and city officials, but the DOJ’s comments to the Vallejo Times-Herald suggest that at a minimum, Vallejo will be expected to implement the 45 reforms that were the subject of the 2020 collaborative review.

“Vallejo City officials have been in ongoing discussion with the Cal DOJ to determine the next steps in our reform efforts. In the meantime, the work we have been engaged in under our collaborative agreement is continuing,” a spokesperson for the Vallejo Police Department wrote in a statement to this newsroom Friday, adding that the department is confident it will successfully implement the remaining reforms.

If the parties are unable to arrive at a consensus, however, the Vallejo Police Department risks further litigation with the state DOJ — and even a trial.

How a settlement could bolster reform efforts

Whether the new phase of oversight will broaden reform requirements in Vallejo will depend on how forceful the settlement provisions sought by the California DOJ will be.

Still, three key aspects are likely to distinguish a court-ordered agreement from Vallejo’s collaborative review.

1. The court has the final say — not Vallejo

Rather than a process based on voluntary participation, court-ordered settlements are ultimately enforced by a judge.

The settlement requirements generally include strict deadlines and progress reporting to the court. If the city and state disagree, the judge has the final word — though the extent of the court’s involvement also varies based on the terms of the agreement.

2. A potential monitor to oversee reforms

In many cases, experts say, court-ordered settlement agreements involve an additional layer of oversight: a monitor, who is appointed to conduct audits, oversee implementation, and measure compliance, among other functions. In its statement to the Times-Herald, the California DOJ suggested that any acceptable agreement would require “strong monitoring.”

Experts say the appointment of a monitor is often crucial to a robust reform effort.

“I don’t know how you can do it without them. You need some level of independent thinking,” said Brann, the co-monitor of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department.

“I understand the downsides of the monitor: they cost money,” said Lopez, who served as a federal court monitor of the Oakland Police Department from 2003 to 2010. “But I do think it’s really important that you have someone whose job it is to make sure they’re doing what they said they would do,” she added. “That can really hold their feet to the fire, and help the public hold their feet to the fire.”

In Kern County, for example, a monitor with full access to the agency’s information and documents completes yearly compliance reports that are made public.

3. There are consequences for not following the rules

A key aspect of judicial oversight is the court’s enforcement powers.

“The court has broad powers to impose any sort of penalty that it wants in order to get the individuals to actually comport with the court’s agreement,” Lopez said. Penalties can include fines or even jail time, although the latter is highly unlikely.

“In a very extreme case, the court can order somebody to become a receiver to essentially provide day-to-day oversight of the department,” Lopez said.

Receivers have broader authority than monitors, which are often called the “eyes and ears of the court,” Lopez added. While monitors observe, review, and report, receivers effectively run the police department.

“Theoretically, that enforcement power is available, people know that. And so that is part of what can keep a city and its police department focused on making these changes,” said Lopez.

Experts said they expect the agreement between the state DOJ and Vallejo to cover a period of between two and 20 years.

A chance for increased transparency

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Mourners kneel next to images of Ronell Foster at a vigil in Vallejo, Calif. on Feb. 13, 2023. Five years earlier, Vallejo Police Ofc. Ryan McMahon shot Foster, who was unarmed, seven times in the back, side, and back of the head after pulling the father-of-two over for allegedly riding his bike in an unsafe manner. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoSeveral experts said they believed it would be beneficial for the attorney general to share the findings of the DOJ’s review in Vallejo and the reasons for deepening involvement.

“You really need to have the public, especially the impacted communities, understand what this is about,” said Lopez.

At the U.S. DOJ, “we would issue these reports that would tell the public what our investigation found,” Lopez said. “I think it’s really important to both the legitimacy and the integrity of the process.”

Some of the experts who spoke to Open Vallejo also believe the community should be involved in the negotiating process itself.

“ACLU and the community and the members that we seek to represent, we think that there’s a lot that should be done. And so we welcome the oversight. And we would hope to be included in the process of working through what a settlement agreement should look like, what it will take for the community to heal and restore trust in its police department.”

Do you have additional comments, questions or concerns? Write to us at [email protected].