This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Open Vallejo. Sign up for ProPublica’s Dispatches and The Vallejo Free Press to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

For more than a decade, the families of those killed by police in Vallejo, California, have pleaded for oversight of their city’s exceptionally lethal police force.

When a series of fatal shootings attracted national attention and the scrutiny of state officials in 2020, Vallejo’s leaders pledged to implement 45 reforms recommended by a private consulting group and overseen by the California Department of Justice. But officials have blown past deadlines and failed to follow through on nearly all of the promised reforms. Reporting by Open Vallejo and ProPublica has found that the city has fully implemented just two.

“We are continuously working on new and revised policies related to the remainder” of the recommendations, a city spokesperson said last week in a joint statement with the police department. “The City and the department have steadily increased the resources devoted to the task, most recently forming a dedicated task force comprised of four full-time dedicated officers.”

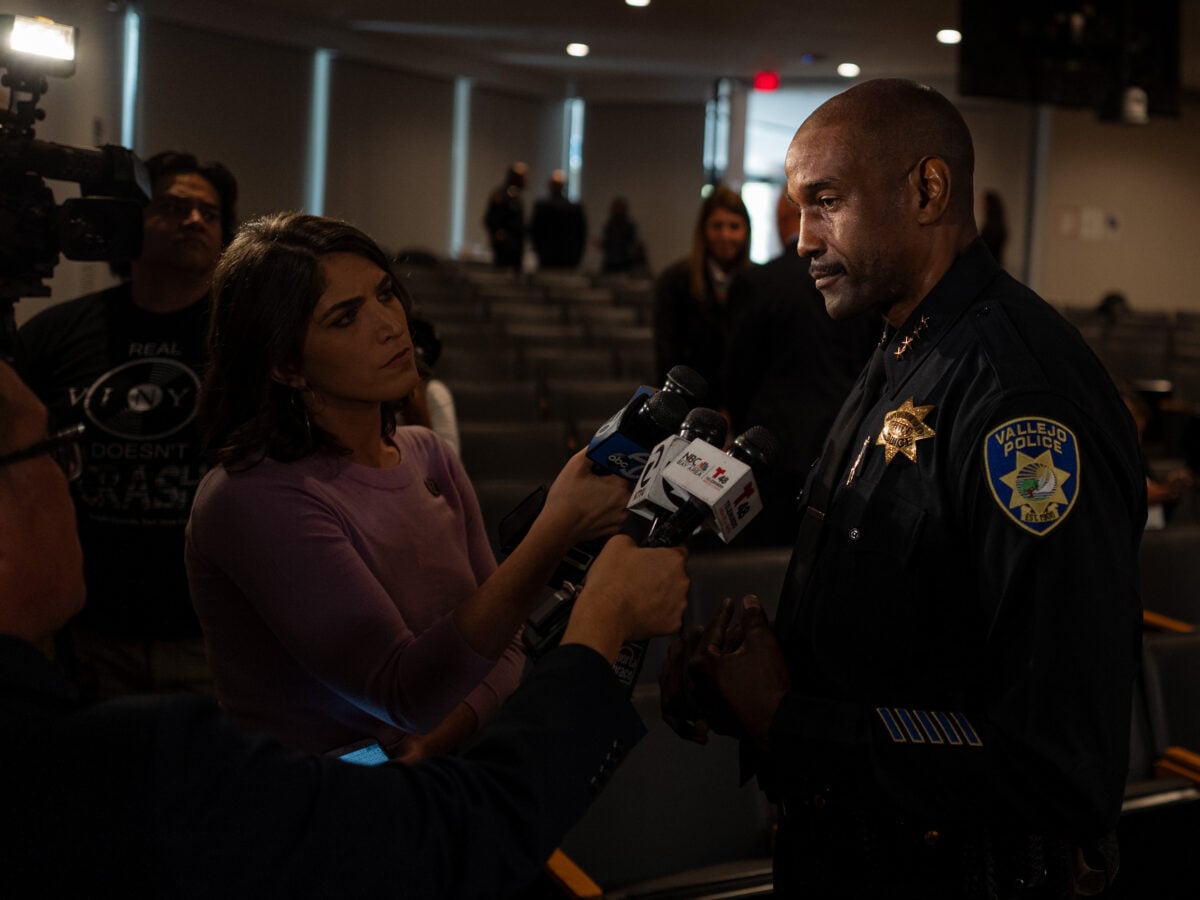

Later the same week, Vallejo Police Chief Shawny Williams, considered a reformer by many, announced his resignation. The newsrooms reported in July how Vallejo police consistently failed to properly investigate killings by officers.

Days after being presented with our findings for that story, the department put out a proposal to begin addressing one of the key recommendations from the state DOJ: to modify how the department investigates fatal shootings and other critical incidents.

But for all its pledges, the city has little to show — and some of the efforts are being impeded by union and city officials.

“All we want is police reform,” Melissa Nold, the local civil rights attorney for two families whose loved ones were killed by Vallejo police, said in an interview. “We thought they would do the right thing, but here we are.”

‘Lack of concrete follow-through’

Things looked like they might begin to change three years ago, after a group of Vallejo officers fired 55 rounds at 20-year-old musician and producer Willie McCoy, who had fallen asleep behind the wheel of his Mercedes, a gun allegedly in his lap.

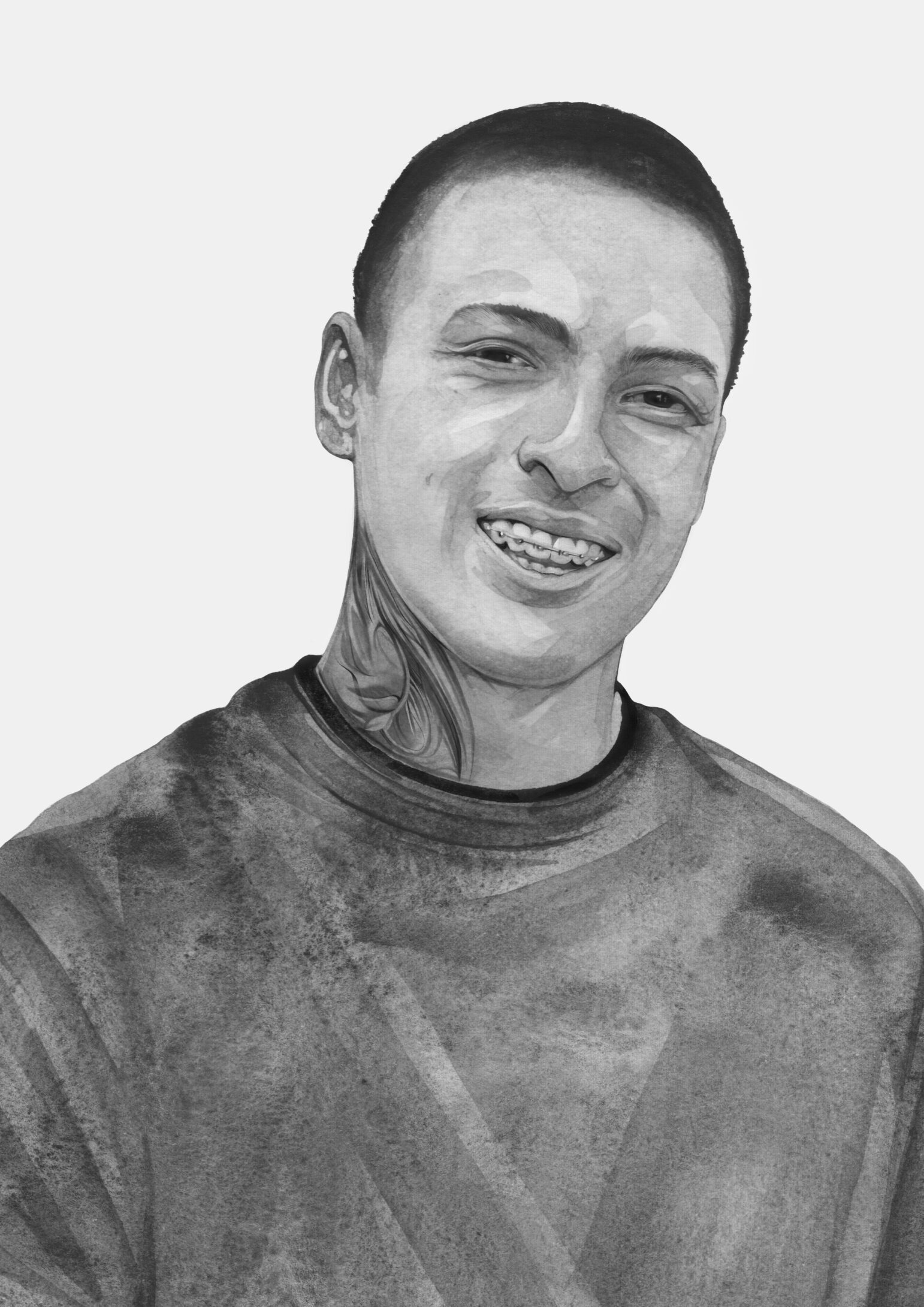

Kate Copeland / Special to ProPublica and Open Vallejo

Willie McCoy Credit: Kate Copeland / Special to ProPublica and Open VallejoMcCoy’s death, in February 2019, garnered national media attention and sent residents to the streets in protest. That summer, amid the public outcry, the department hired a private consulting firm called OIR Group to conduct a “constructive analysis” of its practices.

Roughly a year later the city released the results of the consultants’ work: they identified “timing concerns” — specifically long delays in investigations of police killings — as well as a “lack of concrete follow-through” on the issues identified by those reviews, and an “apparent reticence when it came to finding fault.” They strongly advised the department to revise its system for investigating fatal shootings to ensure comprehensive reviews in “time-appropriate phases.” All in all, the outside firm made 45 recommendations, which also included strengthening reviews of the use of force by officers and creating an independent police oversight body.

Weeks later, in a highly unusual move, the chief fired officer Ryan McMahon for endangering a colleague when he shot at McCoy, records released by the city show. At the time of McCoy’s death, McMahon was already under investigation for killing an African American man. McMahon was the first Vallejo officer to be fired for conduct during a fatal shooting in at least 10 years. (McMahon was not criminally charged in either shooting; he did not respond to requests for comment.)

The OIR Group’s recommendations, however, were nonbinding, and the department did not immediately release plans for implementing them.

Then, less than a month after the reforms were proposed, Vallejo Police Det. Jarrett Tonn fired five rounds from a rifle at 22-year-old Sean Monterrosa from the backseat of an unmarked police truck, public records show. The young Latino man was killed by a single bullet to the back of the head. It was one week after the murder of George Floyd. Tonn, a SWAT officer who participated in three nonfatal shootings since joining the department in 2014, said he mistook a hammer, later recovered in Monterrosa’s sweatshirt pocket, for a firearm. (Tonn was not charged in any of these shootings; the criminal investigation into the Monterrosa shooting is still open.)

Kate Copeland / Special to ProPublica and Open Vallejo

Sean Monterrosa Credit: Kate Copeland / Special to ProPublica and Open VallejoThree days later, on June 5, concerned by the “number and nature” of police shootings in Vallejo, the California DOJ announced that it would conduct a three-year review of the department’s policies and practices — a relatively rare occurrence in California that can open the door to further scrutiny and potential civil or criminal sanctions.

The state DOJ embraced the 45 recommendations that the OIR Group had put forth and set out to evaluate Vallejo’s progress in implementing them. To do that, the DOJ hired Jensen Hughes, a global risk management firm, and defined steps for each reform that Vallejo police had to fulfill before they would deem the department compliant. Williams called the process a “massive review” and agreed to collaborate.

In less than two weeks, the Vallejo Police Department produced a draft implementation plan estimating that the steps for most reforms, including changes to the post-shooting review process, would be completed around February of 2021. But the plan itself noted that the target timelines it was setting did not take into account review by stakeholders like the union. In the end, the department missed more than a dozen deadlines, subsequent reports show.

In March 2021 the department set new goals to complete most recommendations within one year. By May of this year, however, it released a progress report revealing that the police department had achieved DOJ compliance with only one reform: a stricter requirement that officers activate their body cameras and mandated audits of some of the footage. The policy change, instituted by Williams, had been entrenched before the state DOJ’s review even began. (Despite the new policy, none of the officers present during the Monterrosa killing — which took place after this requirement was added — activated their body cameras prior to the shooting; three of the officers involved incorrectly claimed they were not required to turn them on because they were detectives rather than patrol officers.)

Since then, Vallejo has “completed and implemented” just one additional reform: an accountability program to ensure that the body camera policy would be enforced, according to the city’s statement to the news organizations.

“Implementation of new policies is a multi-step process,” the city wrote. The statement also said officials were “optimistic” that with the new task force dedicated to the reforms, moving “to full completion status will occur more rapidly.”

The California DOJ declined to answer specific questions about Vallejo’s compliance with the reform standards. “No public updates to share on our end at this point in time,” the DOJ press office wrote in response to requests for comment. “Our office remains committed to executing the terms of the agreement.”

The Vallejo Police Department also claimed in the May progress report that it had reached the implementation phase for 11 other recommendations. The report underscored changes to the hiring process to prioritize diversity and an increase in civilian staffing to support police services (for example, dispatchers or workers in the department lobby). In his statement to the news organizations the same month, Williams also noted several reform “highlights,” including changes to the department’s de-escalation policy, but did not talk specifically about compliance with the state DOJ’s measures.

As of May, the remaining 32 reforms remained untouched or in draft form, including key changes to how the department reviews fatal incidents and the implementation of an independent police oversight agency. The city did not provide updated information about its progress on the uncompleted recommendations.

‘Resounding’ resistance

The issue of independent oversight, which was recommended by the OIR Group and endorsed by the California DOJ, has become a key point of contention among officials.

City officials, and in one case the police union, have resisted establishing an independent agency with the power to hold the department accountable, sources with knowledge of the matter told the news organizations. They spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss processes relating to the California DOJ’s intervention in Vallejo.

In the fall of 2020, after the McCoy and Monterossa killings, the city asked a coalition of local nonprofits called Common Ground to help research permanent oversight models for Vallejo, an effort soon joined by Mike Nisperos, a retired attorney who is a member of the Vallejo Chief’s Community Advisory Board and a founding member of Oakland’s Police Commission. The city estimated that finding a model would take about six months and planned for a temporary solution in the meantime.

“Independent oversight cannot wait,” Vallejo’s then-city manager wrote in a City Council report advocating for an “interim auditor” to oversee the department. On Feb. 23, 2021, the city unanimously voted to hire OIR Group to review citizen complaints, conduct independent investigations and produce public reports while Common Ground and Nisperos researched a permanent model.

“We can’t have police investigating themselves,” Ashley Monterrosa, the sister of Sean Monterrosa, said at a City Council meeting where she, her sister Michelle Monterrosa and others advocated for strong police oversight.

But even the temporary oversight was never put in place. In July 2021, the Vallejo Police Officers’ Association sent Williams a cease-and-desist letter, obtained by the news organizations, demanding that the city refrain from hiring the independent auditor. The union alleged that the city violated California law by failing to consult with union officials, and it threatened to file a complaint with the state. Nisperos said he believed the pressure by the union may have caused the interim oversight proposal to falter.

The union, Williams, the city and city attorney, and the OIR Group did not comment on what happened with the interim proposal.

As the interim solution stalled, Nisperos and Common Ground continued to advocate for permanent oversight and produced a 40-page draft ordinance that would have created three branches of oversight, including a community review agency with the power to investigate fatal shootings and other incidents. Nisperos and Common Ground gathered feedback on the draft from all seven members of the Vallejo City Council, Williams, police oversight experts, residents impacted by police violence and the state DOJ.

Despite repeated requests, however, Vallejo City Attorney Veronica Nebb did not provide feedback on the draft for more than a year, Nisperos said, adding that he considers Nebb a “deliberate impediment” to reform.

The city disputed this assessment. “The City Attorney, in conjunction with the City Manager, have worked to build consensus with the community through numerous community meetings as well as meetings with Police Department leadership, the unions, and sworn and civilian staff,” the city wrote in a statement to Open Vallejo and ProPublica. The statement also said that between them, the city attorney and city manager had met with Common Ground three times since 2020, that they had reviewed the draft and that they would meet with the group again once the new ordinance was produced, this or next month. “Consensus-building efforts have always been in place and will continue.”

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Michelle Monterrosa urges the Vallejo City Council to establish independent oversight of the city’s police during a council meeting on August 23, 2022. A Vallejo police detective with three prior nonfatal shootings killed Monterrosa’s brother Sean in 2022 after he mistook a hammer in the 22-year-old’s sweatshirt for a gun. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoIn August, Nebb — who plays a major role in handling the oversight reform — announced during a council meeting that the city could soon “begin to look at drafting” oversight legislation. Her 55-minute presentation did not address the draft ordinance that had been circulating among city officials for nearly 18 months.

“You have people who dedicated two years to put in research, to putting a model together for you,” Michelle Monterrosa said about the Common Ground ordinance at the meeting. “Let’s stop wasting time.”

Several elected officials at the meeting agreed. “I’m just ready to go on this, I’m ready to have something put in place,” Councilmember Mina Loera-Diaz said.

“The resistance from the city attorney’s office was resounding,” Councilmember Tina Arriola said in a September interview. “There’s just no budging.”

In presenting the city’s plan to draft its own ordinance, Nebb had raised concerns that an oversight body with the power to implement discipline or overrule the chief’s decisions could scare off potential police recruits. Advocates are concerned that she will water down the powers of the oversight agency. Nebb did not respond to specific questions about these efforts.

But barriers did not only originate from the union or city attorney’s office.

The union itself suggested in a May statement to Open Vallejo and ProPublica that the now-former police chief too has been an obstacle to change, and it claimed it had tried to set up meetings to discuss a handful of reforms but had gotten close to “zero response from the city.”

Williams, who has repeatedly expressed support for the reforms, did not respond to questions about the union’s claim.

In September, a representative for Jensen Hughes, the firm hired by the state DOJ, told Williams that it had developed “defined concerns” that a lack of involvement of top leadership was affecting the reform efforts, according to an email disclosed in response to a public records request. The email outlined several matters requiring “leadership” that instead were being left to lieutenants. A spokesperson for Jensen Hughes declined to comment for this story, and Williams did not comment on the firm’s findings.

A few weeks later, Williams unexpectedly took three weeks off and subsequently announced his resignation.

With a council election this week and less than eight months left until the end of its three-year agreement with the California DOJ, Vallejo could exit state supervision with no independent oversight, unless the state decides to extend — or escalate — its intervention in Vallejo.

“They want to continue doing what they’ve been doing for 20 years,” said Willie McCoy’s brother, Kori McCoy, about Vallejo’s handling of the reforms. McCoy’s family, who supports the Common Ground proposal, is demanding that the city implement the oversight ordinance as part of their civil rights lawsuit against the city; their attorney, Melissa Nold, said they will not accept any settlement money unless officials agree to impose outside oversight on the police.

“I don’t see how you’re going to fix the problems with the same people,” McCoy said. “Police run that city, and people are afraid.”

Reporting for this project was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.