Vallejo Police Department

Members of the Vallejo Police Department stand in front of their headquarters in a photograph dated 1915.For Vallejo police, opacity and impunity are standard operating procedure. Theirs is a culture that insulates officers who perform gang-like rituals after killing. Colleagues who dare question unethical, immoral, or illegal conduct say they are targeted for retaliation. City leadership lacks the will to hold the department’s worst officers accountable.

It is time to disband the Vallejo Police Department and start anew.

Six years ago, my wife Denise Huskins and I were subjected to the department’s malice after she was kidnapped from my home. Without evidence, Detective Mat Mustard and others falsely accused me of murder while ignoring leads that would have led them to Denise. When she was released alive, we were immediately accused of fabricating her kidnapping and sexual assaults. The department spokesperson, Lt. Kenny Park, called a press conference in which he made statements that severely damaged our reputations. All of this occurred while the true perpetrators remained at large. One of them was eventually caught by a different agency after he attacked another family a few months later. He was convicted in that case, as well as ours, and is now serving a 40-year sentence in federal prison.

Yet despite these failures, nothing changed. Officers central to the investigation, like Mustard, have been promoted. (Mustard, the longtime president of Vallejo’s police union, received Vallejo’s “Officer of the Year” award following Denise’s kidnapping.) . Former Police Chief Andrew Bidou has never been held accountable for allowing his officers to bungle the investigation. In fact, the city council planned to install Bidou as interim chief upon his retirement in 2019, effectively doubling his pay to almost $40,000 a month until his replacement could be selected. It seems no one in city leadership questioned why the search for a new police chief didn’t start the year prior.

Thankfully, Open Vallejo uncovered this cash grab, which the city abandoned after it was found to violate California’s public retirement rules. While Vallejo officials continue to benefit from their misconduct, the community suffers, with the harm falling disproportionately on Vallejo’s Black and brown residents. I cannot speak to the horror of having one’s child stolen by police violence, which happens more often in Vallejo than almost anywhere else in California. I can speak only to my own experience with Vallejo police — a false accusation that changed me forever.

Mike Jory / Vallejo Times-Herald via AP

Denise Huskins and Aaron Quinn turn to each other at the end of a news conference on Monday, July 13, 2015, in Vallejo, Calif. At left is Huskins’ attorney, Douglas Rappaport and second from right is Quinn’s attorney, Daniel Russo. The lawyers for the couple in the kidnap-for-ransom case that police called a hoax are blasting investigators and asking that authorities set the record straight. Credit: Mike Jory / Vallejo Times-Herald via APEvery day I wake up grateful that Denise and I are still alive. I also carry trauma from being turned into a villain when we were in fact victims. We were ostracized from the community, the place where I bought my first home, and where, as physical therapists, we treated people who suffered neurological and other injuries. We would cheer for the Giants at Mare Island Brewery and play basketball at the local recreation center. We were establishing our roots in Vallejo until the kidnapping and subsequent police misconduct upended our lives.

Ultimately we were forced to sue the city that we love; it was the only way to ensure some level of accountability for the damage done by Vallejo police. We hoped our lawsuit might lead to some positive change. But the city would rather pay attorneys to fight families who have lost loved ones than investigate the officers who celebrate death with barbecue and a bent badge.

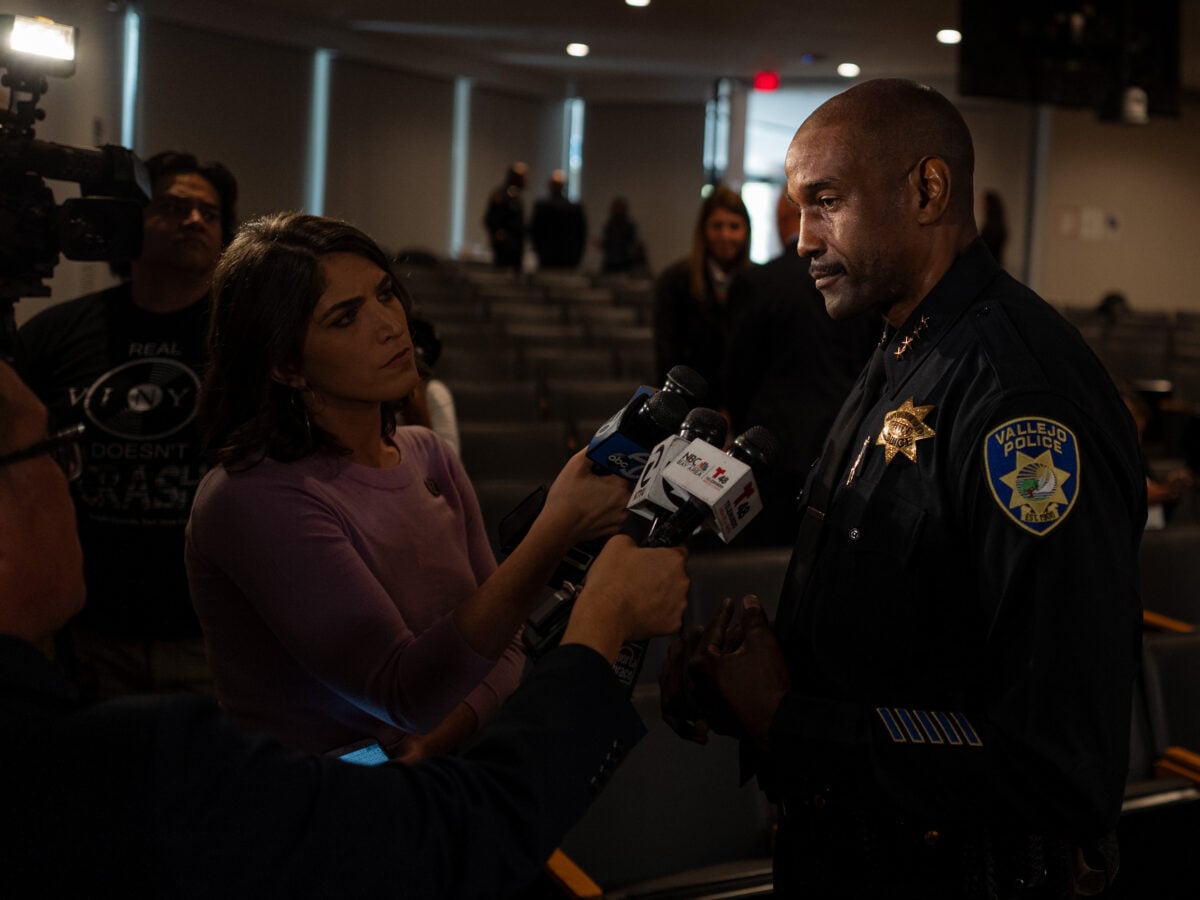

Unfortunately, Vallejo’s new Chief of Police Shawny Williams seems unlikely to change the violent, aggressive culture that has been entrenched in the department for decades. For example, Williams speaks often of transparency and accountability. But it took Vallejo police more than a month to release video from the June 2 killing of Sean Monterrosa. A detective with three prior shootings shot Monterrosa with a high-powered rifle after supposedly mistaking a hammer in his hoodie for a gun.

When the department finally released some body camera footage of the incident, it did so in the form of a montage prepared by a public affairs firm. None of the body camera footage depicted Monterrosa until after he was shot; the only video of the killing was lost forever, the data overwritten with zeros.

Facing legal demands from the ACLU and Open Vallejo, the department uploaded additional footage on a Friday afternoon several weeks later — a tactic often used by those seeking to minimize public attention. A month after that, and under the same legal pressure, the city released additional footage of officers killing Willie McCoy in February 2019. All of the footage that was eventually released is information the public has a right to see. It should have been disclosed right away.

The department made other attempts to control the narrative around Monterrosa’s death. For example, Williams took pains to discuss the dead 22-year-old’s alleged criminal history during an initial press conference following the shooting. The information had no bearing on the previous night’s events, which begs the question — did Williams seek to imply that Monterrosa somehow deserved his fate?

The Vallejo Police Officers’ Association was more overt about blaming the victim. In a statement released three days after the shooting, the union accused Monterrosa of taking a “tactical shooting position,” notwithstanding the fact that he was unarmed. Written by a union-affiliated lawyer, it claimed, “At no time did Mr. Monterrosa make any movements consistent with surrendering.” Although this appeared to contradict Williams’ description at the June 3 press conference, the Chief’s story would soon converge with the union’s.

All the while, the police union complains about funding and staffing levels, even though police account for 45 percent of Vallejo’s General Fund. In addition, two dozen cases involving Vallejo police will cost the city and its insurers upward of $50 million in the coming years, according to an estimate the city attorney’s office prepared last year. At the same time, the union resists basic oversight, such as drug testing officers who shoot and kill civilians, or those who get in serious car crashes. There is no reforming such a parasitic culture.

Vallejo needs officers who view themselves as guardians, not warriors. The only way this appears possible is if the city follows the model of Camden, New Jersey by disbanding the entire department and starting over — while also learning from that city’s mistakes. Officers who wish to re-apply for their jobs should. Those who decline are free to work in the private sector. This will allow the department to rid itself of the officers who perpetuate the current toxic culture while providing an environment for competent officers to flourish. Critically, the city needs to establish community oversight, with the power to investigate wrongdoing and impose discipline. Anything less keeps the status quo that only benefits those who abuse their power.

Many Vallejo residents have feared the city’s police for decades. We came to fear them, as well. But police officers are public servants, and things can change for the better. Vallejo is a creative and resilient city that can lead the way in establishing new models of policing based on fairness, respect, and accountability.

Op-eds are contributed by people from outside this news organization. They represent the views of the author.