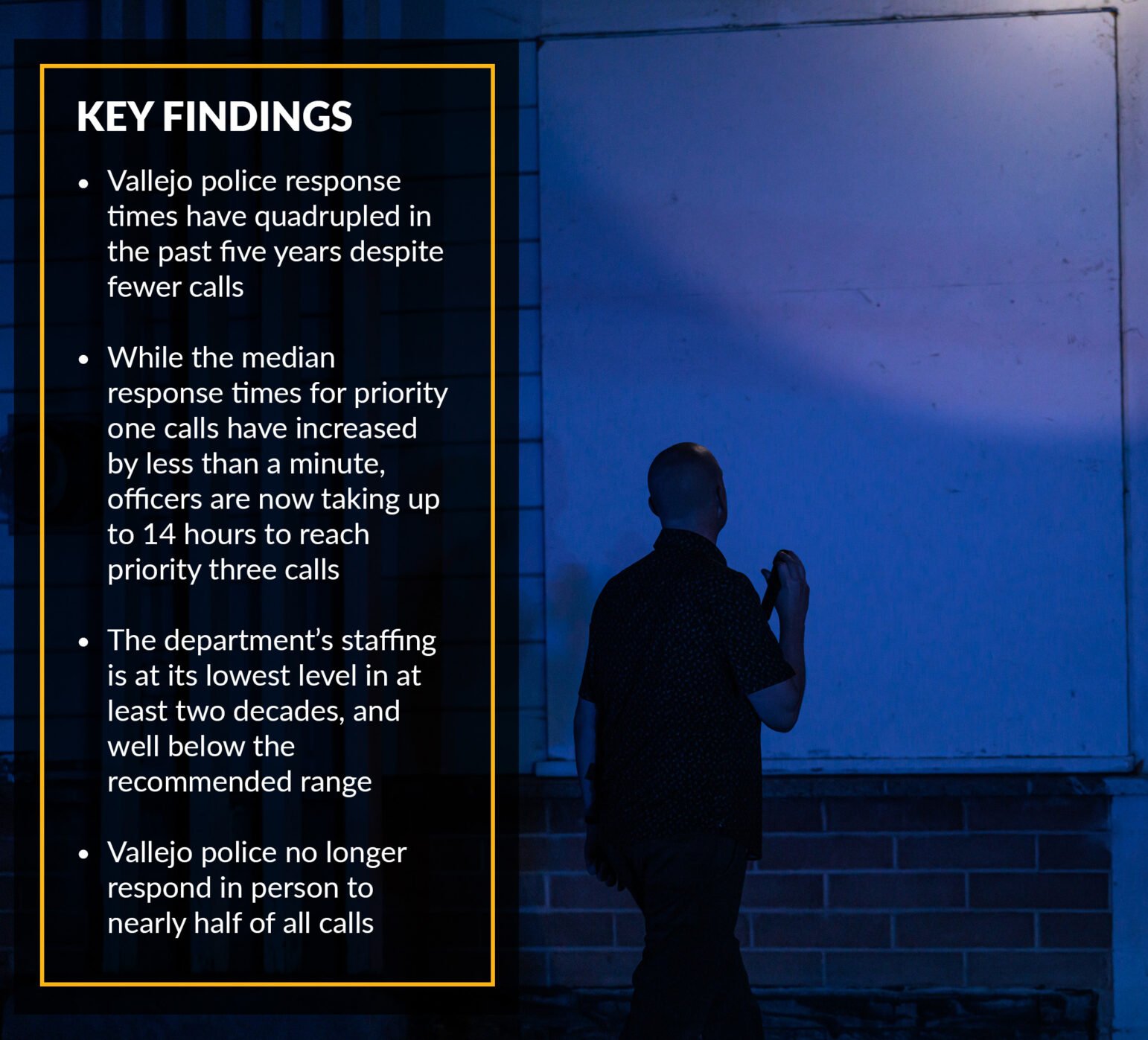

Vallejo police are taking longer to respond than at any time in the past five years despite a steady decline in the number of calls for help, an Open Vallejo investigation has found.

The Vallejo Police Department’s median response time for all calls has quadrupled since 2019 as the agency’s staffing has dwindled, data shows. With a sluggish police response to all but the most critical incidents, some residents say they feel abandoned by the city’s police force and left to deal with a slew of issues — domestic violence, sideshows, and catalytic converter theft, for example — on their own.

“Everyone calls the police, and the police do not come,” said Paula Conley, a Vallejo native. “It would be like winning the lottery if you seriously needed police and they showed up.”

Open Vallejo analyzed five and a half years of Vallejo’s calls for service data, which the newsroom obtained through a public records request. For all types of calls, the median response time — measured as the time between the department receiving the call and an officer arriving on the scene — jumped from 26 minutes in 2019 to 105 minutes in the first half of this year, data shows.

But much of that slowdown stems from the agency’s handling of priority two and three incidents. These make up the vast majority of calls for service and typically take hours for officers to reach. The agency’s median response time for potentially life-threatening priority one calls, meanwhile, has held relatively steady, climbing by less than a minute over the past five years.

Vallejo police spokesperson Sgt. Rashad Hollis said response times have grown longer in part because of the agency’s severe staffing shortage, which the Vallejo City Council proclaimed a local emergency in July 2023. The agency currently employs 73 sworn personnel — just 53 percent of its allocated positions and the lowest level in at least two decades.

“We do recognize the impact that the response times have on our community’s safety and trust,” Hollis said. “Once we improve our staffing, we’ll definitely improve our response time.”

Fewer calls, but longer waits

Notifications began flooding Mary Madrigal’s phone one morning in April 2022 while the South Vallejo resident was at work. When she checked her home security cameras, she saw two masked men carrying tools toward her truck. Through the audio function of her home cameras, she warned them: “Get away from my car. I’m calling the police.”

“He was like, ‘Call them,’ in a joking way,” Madrigal recalled in a recent interview with Open Vallejo. “He knew they weren’t going to show up.”

Madrigal called 911 as the men slid beneath her vehicle and removed its catalytic converter. She played the surveillance footage so the dispatcher could “hear the sawing in the background.” But the dispatcher said no units were available and instructed Madrigal to file an online report. When she did, police took no apparent action, Madrigal said, an experience that left her “extremely frustrated.”

“Nobody was hearing me,” she said. “Unfortunately, I feel like I just live in Vallejo, but I’m not a part of this community. It’s not a place where I feel safe.”

Madrigal’s experience is far from isolated. Data shows that officers do not respond in person to a growing portion of residents’ calls for help — despite a decline in the overall number of calls.

In 2019, the department provided no in-person response to 40 percent of the city’s 911 calls, most of them labeled as priority two- or three-level incidents, data obtained by Open Vallejo shows. That portion reached more than 50 percent last year and remained at 47 percent in June. (The calls lacking an on-scene police response include canceled calls, incidents that officers were unable to locate, and ones in which police provided services over the phone or online.)

Meanwhile, the number of emergency calls in Vallejo has steadily decreased in the last five years, according to the department’s data. The agency received roughly 59,000 calls for service in 2019 and nearly 51,000 calls from residents in 2023. Data shows that police have received nearly 25,000 calls through June this year.

Even with fewer calls to handle, the median response time for priority one calls rose from 5 minutes and 56 seconds in 2019 to 6 minutes and 49 seconds this year, the data shows.

“That’s not bad at all,” said Ian Adams, an assistant professor of criminology at the University of South Carolina and a former police officer. Given the agency’s staffing levels, he said, “They’re working hard.”

While there is no national standard for response times, experts told Open Vallejo that departments across the country often aim for a median response time of three to five minutes for the most serious emergencies. Vallejo’s goals are to respond within six minutes for priority one calls and anywhere from 12 to 20 minutes for priority two calls, according to Interim Police Chief Jason Ta, who has publicly acknowledged that his agency’s response times need to improve. He did not respond to requests for comment on this article.

Elsewhere in the Bay Area, law enforcement response times — and the way they are measured — vary widely. From the time of dispatch, officers in Santa Clara responded to priority one calls in 2 minutes and 35 seconds on average last year. The city has roughly the population of Vallejo but more than double the number of sworn staff.

In San Francisco, the median response time for urgent calls has hovered between 8 and 9 minutes over the past three years; while a city audit last year found a “significant staffing deficit” in the police department, San Francisco had roughly three times as many officers per 100,000 people as Vallejo at the time.

Meanwhile, Oakland’s average response time for high-priority calls topped 30 minutes last year; the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services threatened to withhold funding from the city’s dispatch center as it struggled to answer enough calls within the state-mandated 15 seconds. As of July, Oakland had 160 sworn personnel per 100,000 residents, which is well below the statewide ratio but nearly three times that in Vallejo.

‘They’re not coming’

In Vallejo, as officers scramble from one critical call to another, response times for calls deemed less urgent have slowed more drastically.

Five years ago, Vallejo police responded to 90 percent of all priority two calls within two hours, with a median response time of 25 minutes, according to the data. These calls include felonies that have just occurred or misdemeanors and property crimes that are in progress, such as reported prowlers, accidents with minor injuries, and domestic violence incidents, including those with reported injuries, public records show.

Since then, the median response time for such calls has more than tripled, standing at an hour and a half this year through June, according to the data. But a significant portion of callers waited much longer. In 90 percent of cases, officers reported their presence on the scene within 10 hours.

For priority three calls, which include property crimes that pose no immediate threat to life, the median response time has jumped from 36 minutes in 2019 to 152 minutes this year. Five years ago, officers reached 90 percent of such calls within about 3 hours, but that timeframe has now stretched to more than 14 hours.

One such call came last year on New Year’s Day from Nicole Hodge, who reported an early morning burglary at Provisions, her restaurant on Virginia Street. Someone had smashed a window and stolen the cash register, Hodge said, and other downtown businesses were similarly targeted around the same time.

When three officers walked into the cafe later that morning, Hodge said she was surprised by their quick response. Then she realized they knew nothing about that morning’s reported burglary. Rather than collect evidence or take a report, she said, the officers asked for a table. “They just wanted to eat breakfast,” she said.

Frustrated by that incident and others like it, Hodge said she has grown weary of filing police reports and “realizing nothing happens.” When business owners met with police later that year to address the rash of burglaries, Lt. Steve Darden told Hodge she could buy a gun for protection, she said.

To Hodge, the message from Vallejo police was clear: “They’re not coming.”

Hollis, the department’s spokesperson, said he was present at the meeting and witnessed the exchange. The lieutenant’s remark was not intended to convey that message, he said.

Such experiences can have a significant impact on public safety, experts say. Adams, the criminologist, said lengthy response times for even the least urgent calls can deter residents from reporting crime, hamper criminal investigations, and impact a department’s public image.

“Nobody likes waiting around after a fender bender for three hours for the police to get there,” he said. “That begins to drag on public perception about the effectiveness of police.”

Additionally, slow response times can further deteriorate a community’s trust and confidence in its police department, said Niles Wilson, the senior director of Law Enforcement Initiatives at the Center for Policing Equity, a research center headquartered in Denver. This is especially true in places where the relationship between law enforcement and community members is already strained, he said.

“If that has not been addressed or that community healing still hasn’t taken place, when police take a long time, your community may interpret that as, ‘They don’t care,’” said Wilson, a former police executive in New Jersey. “You don’t want your community to ever feel that you don’t care.”

In Vallejo, decades of police violence have fractured the department’s relationship with the community, which has long voiced frustration, anger, and hurt over the city’s lack of accountability or transparency surrounding dozens of fatal police encounters.

Open Vallejo recently revealed that the department covered up one in-custody death for nearly a decade, hid the details of four others from public scrutiny, and destroyed key evidence in multiple fatal police shootings. In 2020, this newsroom exposed a secret ritual among officers who for years bent the tips of their badges to commemorate killing civilians.

That same year, Vallejo police violence sparked an investigation by the California Department of Justice, which entered into a settlement agreement with the city outlining a set of policing reforms this April. The agreement includes no changes related to the agency’s response times, although residents raised the issue repeatedly in a recent listening session with Jensen Hughes, a consulting firm tasked with evaluating the department’s reform efforts.

‘A math problem’

As Vallejo’s response times lag, recent research has confirmed the connection between an agency’s staffing levels and its ability to respond quickly to calls for service. When Adams and other researchers studied the Salt Lake City Police Department, they found that low staffing had an especially large impact on less urgent calls. After the department lost a fifth of its officers in a year, response times for lower priority calls “went through the roof,” he said.

“When your police staffing shrinks or stays stagnant in the face of growing demand, it’s just like a math problem — you’re going to see increased response times,” Adams said. “Without staffing, you just can’t get out of this problem.”

Data shows that agencies across California have struggled to recruit and retain officers in recent years. The state lost 2,100 sworn law enforcement officers in 2021, according to the Public Policy Institute of California, and the number of patrol officers dropped to 169 per 100,000 residents that year, the lowest ratio since the early 1990s.

In Vallejo, the rate is much lower still, with 27 patrol officers per 100,000 people. The city’s patrol staffing now stands at little more than half of what the department considers an optimal level, according to Ta.

The department’s sworn staffing has plummeted by roughly a quarter since 2019 amid highly publicized scandals, tumultuous leadership, and the halting reform effort imposed on Vallejo by the state DOJ.

Following a major decline related to Vallejo’s bankruptcy in 2008, police staffing remained below capacity but held relatively steady from 2014 to 2020; in each of those years, the department employed more than a hundred sworn officers, according to Ta’s presentation.

However, the department has lost more officers than it hired in all but one of the last five years, with significant numbers departing in 2021 and 2023, public records show.

Mayor Robert McConnell wrote in an email to Open Vallejo that he believes response times will improve when Vallejo hires more police officers and finalizes a proposed agreement with the Solano County Sheriff’s Office for additional law enforcement services. In August, the California State Assembly passed legislation aimed at relieving Vallejo’s staffing shortage by allowing retired officers, evidence technicians, and dispatchers to temporarily return to full-time work at the Solano County Sheriff’s Office.

“Many plans have been put into place,” McConnell wrote. “Now the city needs to find the personnel as employees to implement those plans.”

In the meantime, Vallejo has supplemented its patrol division by downsizing other special assignments, said Hollis, the Vallejo Police Department spokesperson. The agency collapsed its traffic division and temporarily assigned detectives to patrol shifts on a rotating basis. It also dissolved a team that was responsible for engaging with the community and addressing issues like blight, homeless encampments, and prostitution, Hollis said.

In 2022, the Vallejo Police Department obtained grant funding to deploy a team of non-police first responders to calls for welfare checks, mental health crises, and other social service calls during daytime hours. The six-member unit, known as IHART, responded to more than 400 calls from its launch in mid-April through June, with an average response time just under 10 minutes, according to the city.

As of July, Vallejo also had seven police assistants assigned to the patrol division who deal with incidents that do not involve danger or confrontation, such as evidence collection, victim interviews, or report writing, according to the department. Ta said he hopes to fill three remaining police assistant vacancies, although several positions are only temporarily funded with American Rescue Plan Act funds.

Wilson, the Center for Policing Equity director, said such alternative response models are a smart strategy for reducing response times without hiring more officers. Ideally, officers and dispatchers should be freed up to handle urgent calls, he said.

“Those needs that are of less priority can still be addressed without it taking almost three hours,” he said. “That just makes people angrier.”

New projections from the Vallejo Police Department show the agency expects to add seven officers per year — a rate at which it would take nearly a decade to fill its authorized positions.

“You have to squint your eyes to see the light at the end of the tunnel,” Councilmember Tina Arriola said after Ta concluded his presentation. “But it’s there.”