Since 2019, the city of Vallejo has become synonymous with police violence, fueled by local and national news stories over the police department’s high rate of fatal shootings.

Now, the city’s impunity may be coming to an end.

This week, California Attorney General Rob Bonta is expected to file a lawsuit in Solano County Superior Court alleging that the Vallejo Police Department has routinely violated individuals’ constitutional rights, necessitating court-ordered reforms, a half-dozen people with knowledge of the matter told Open Vallejo. The state DOJ will also file a stipulated judgment, otherwise known as a consent decree, that lays out the steps Vallejo must take to reform its police force.

The sources spoke with this newsroom on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss sensitive conversations within and between the city and the state DOJ, which at times grew rancorous as frustrations mounted over Vallejo’s failures to reform voluntarily, others with knowledge of the process said.

Spokespeople for the Vallejo Police Department and the city of Vallejo did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The lawsuit and consent decree against Vallejo are likely to resemble reforms the attorney general imposed on the Bakersfield, Calif. Police Department in 2021, sources said. In a complaint filed in Kern County Superior Court in August of that year, Bonta accused Bakersfield police of failing “to uniformly and adequately enforce the law, in part because of inadequate policies, practices, and procedures,” thus depriving individuals of their constitutional rights. The accompanying consent decree contained 40 pages of detailed reforms, all overseen by a judge and a court-appointed monitor tasked with auditing the department’s progress. The reforms efforts are ongoing.

The Vallejo consent decree is said to be similarly “sweeping” and “comprehensive,” according to a source familiar with the Justice Department’s thinking. Another source described it as “intense” and “a long time coming.” Neither person had seen the final document, access to which appears to be limited to a small number of lawyers in the state DOJ and Vallejo city attorney’s office.

“It’s been kept pretty secret squirrel from what I hear,” a source with knowledge of the announcement said.

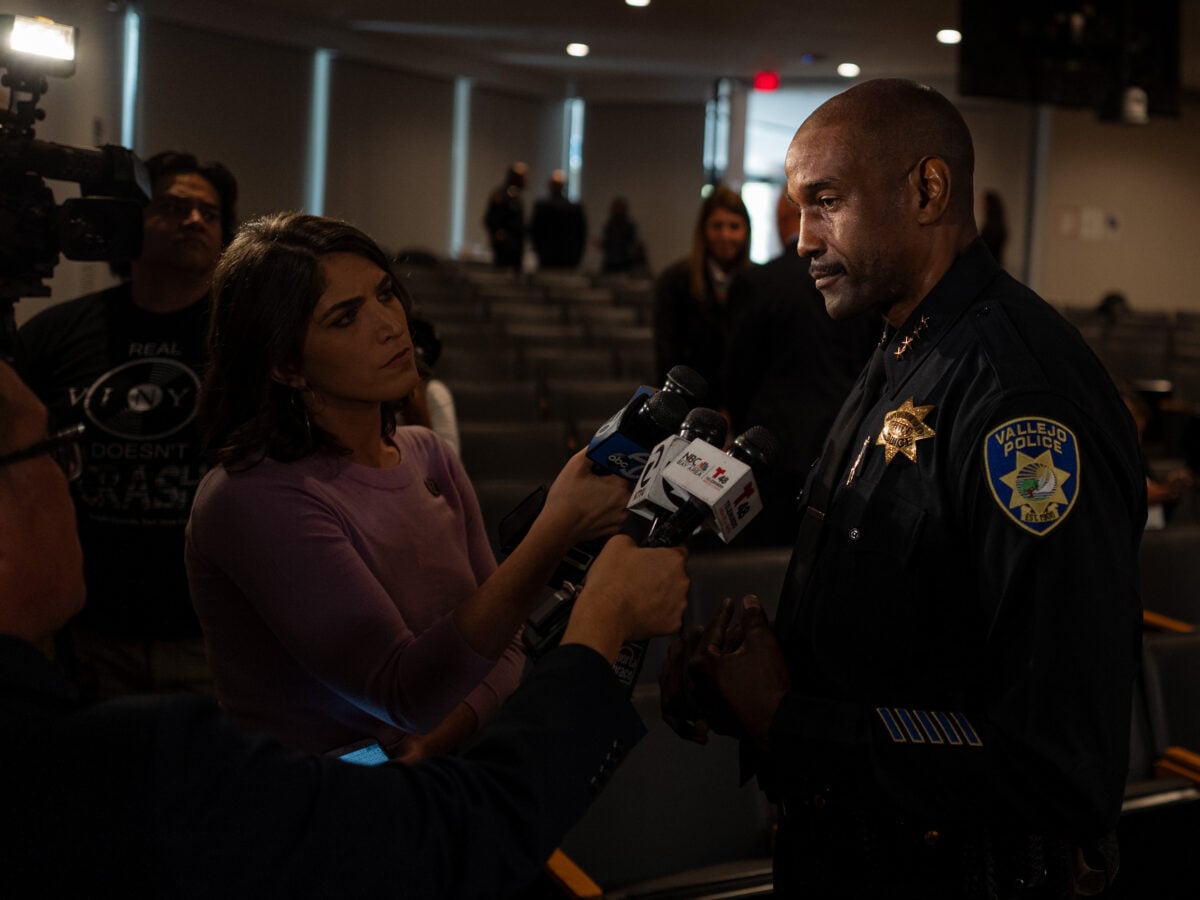

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

California Attorney General Rob Bonta speaks to the press on May 10, 2023 in Oakland, Calif. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoThe consent decree comes at the end of a yearslong effort by the state DOJ to help the Vallejo Police Department reform itself, which began with an initial investigative subpoena in May 2020. Weeks later, a Vallejo detective with three prior shootings killed 22-year-old Sean Monterrosa with a rifle after allegedly mistaking a hammer in the young man’s pocket for a gun. Days after that, Bonta’s predecessor Xavier Becerra announced a three-year collaborative reform agreement with the city prompted by the “number and nature” of police shootings here.

The following month, in July 2020, Open Vallejo revealed a Vallejo police tradition in which officers bend the tips of their badges to mark fatal shootings, intensifying scrutiny of the department.

Despite the pressure, the reform efforts soon stalled.

In November 2022, Open Vallejo and ProPublica revealed that Vallejo police had completed just two of 45 reforms endorsed by the state DOJ. At a press conference this May, Bonta told this newsroom that a civil rights investigation was “on the table” in Vallejo.

“We had the cooperative reform, collaborative reform approach in Vallejo,” the attorney general told Open Vallejo. “And so we’re going to have to determine what happens next.”

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Avi Frey (right), of the ACLU of Northern California, speaks alongside his colleague Marshal Arnwine at a town hall to discuss police reform on Oct. 4, 2023 in Vallejo, Calif. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoThat same week, with the reform agreement about to expire, police command staff admitted that the department was “substantially compliant” with just eight reforms.

All the while, scandals continued to mount: the deputy chief, who now leads the department, allegedly arrived at a SWAT callout reeking of alcohol and later canceled a body camera analysis program after it allegedly began to surface unprofessional behavior by officers; a senior city attorney responsible for defending civil rights lawsuits authorized the illegal destruction of evidence in multiple police killings and tried to keep the details of other deaths in custody a secret; and the officer who killed Monterrosa had his termination overturned, in part due to missteps by the department’s command staff. Then, in June, a Vallejo police officer shot someone for the first time in over three years.

However sweeping Vallejo’s forthcoming consent decree may be, it will almost certainly provide only forward-looking relief, according to Avi Frey, Deputy Director of the Criminal Justice Program at the ACLU of Northern California, which provided input on the document.

At a town hall meeting on Oct. 4, Frey told a crowd of more than two dozen Vallejoans that he tried to convince the state DOJ to investigate past killings by officers.

“We said to them, this is a community that’s in pain. You’re not going to solve any problems with a bunch of papers saying, ‘This is best practices for this policy,’” Frey said.

“They weren’t hearing it.”

The California Department of Justice did not immediately respond to a request for comment.