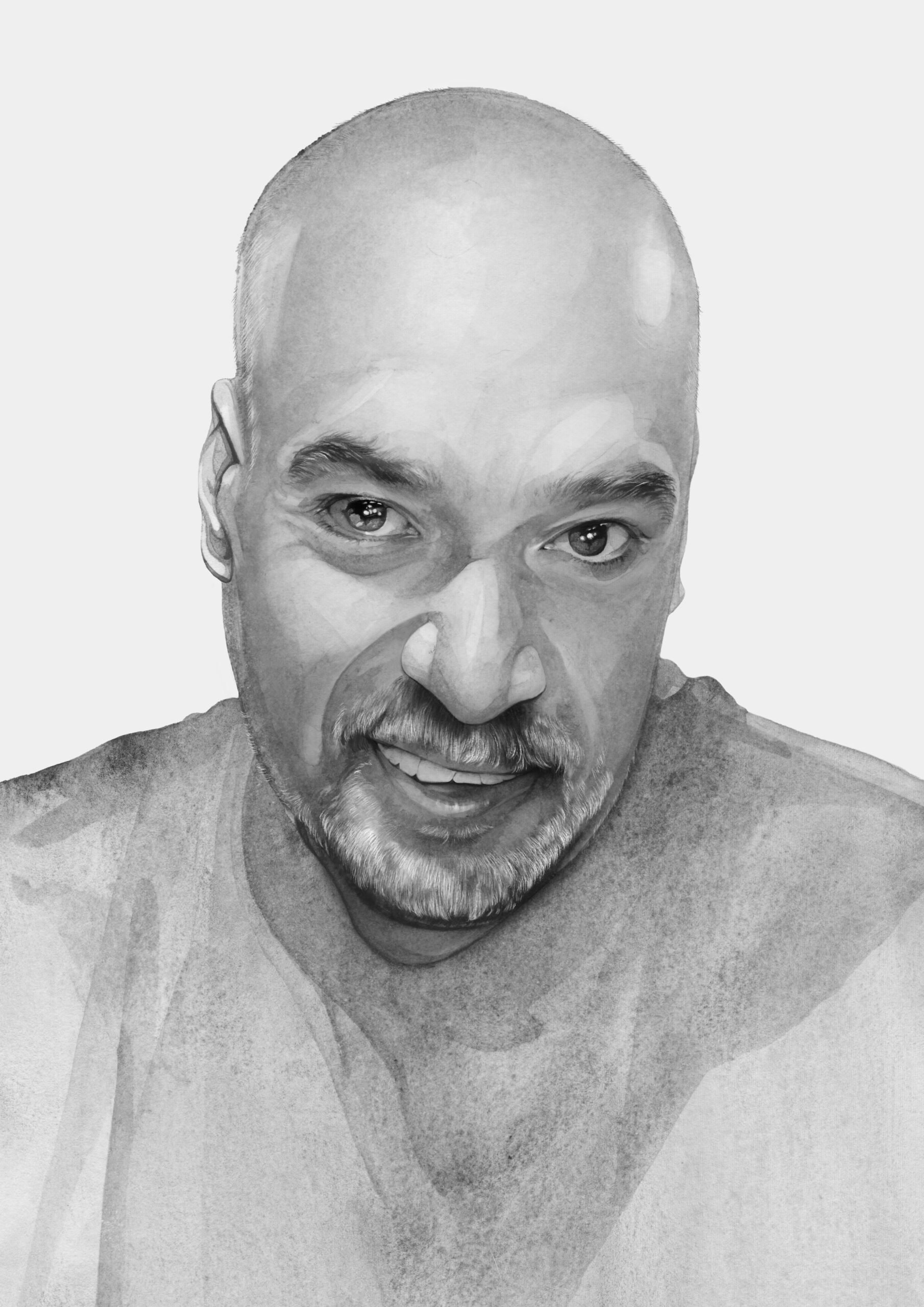

Darryl Dean Mefferd was not under arrest on the evening of Dec. 7, 2016.

He was feeling sick.

The night before, the 49-year-old Vallejo, Calif. native was his usual, gregarious self, his niece Courtney Mefferd told Open Vallejo. He prayed the rosary with his mother and headed to Courtney’s home to help her daughter with a school project. A proud Latino and Indigenous man, Mefferd was the family clown — large, loud, and always ready to wrap his niece in a bear hug.

But when Mefferd returned to Courtney’s home that afternoon, he was withdrawn, disoriented, and dehydrated. Courtney could see white froth accumulating at the corners of his mouth. She handed him a water bottle.

When Mefferd told her he was worried that a man was observing him from a tree, Courtney loaded her uncle and kids in the car, put on his favorite gospel song, and headed to the hospital. Mefferd, a heavy drinker, voluntarily checked himself in for alcohol withdrawal, records show.

Mefferd spent close to eight hours at Sutter Solano Medical Center, where he was treated with vitamins and Ativan, a sedative, according to medical records. Although he was stable, an emergency room doctor recommended admitting him to the hospital as a precaution, records show. Mefferd declined but stayed there while his test results were pending.

Agitated and anxious, Mefferd left the emergency room around 11 p.m. wearing the clothes he arrived in, records show. A nurse called his sister, Cindie Mefferd. On her way to the hospital, Cindie saw a Vallejo police cruiser speed past her on Tuolumne Street, she told Open Vallejo.

It was a busy night at Sutter Solano, nurses later told investigators. Shortly after Mefferd left the emergency room, hospital staff called Vallejo police regarding a “separate and unrelated” incident, according to Solano County Sheriff’s Office records obtained by this newsroom. A woman who was at the hospital on an involuntary mental health hold, known as a “5150,” had removed her clothing and wandered off into the chilly night.

The responding officer, Jeremy Callinan, encountered Mefferd instead. Hospital staff had already found Mefferd ineligible for a 5150, which requires that a person be a danger to themselves or others; they never called the police on him, records show. But when Cindie pulled into the parking lot, Callinan had handcuffed Mefferd and was leading him into his patrol vehicle.

Cindie could see her brother in the back seat, rocking back and forth. Callinan told her that Mefferd was not under arrest. Cindie insisted that she be allowed to take her brother home, but the officer said he was taking Mefferd to the Solano County Crisis Center, a mental health facility in nearby Fairfield.

“Cindie, they are going to kill me,” Mefferd shouted as the police cruiser began to pull away.

Less than 30 minutes later, steps from the crisis center, Mefferd lay facedown, handcuffed, and unconscious, according to law enforcement and medical records. By the time backup arrived, he was no longer breathing.

‘Mechanism of death’

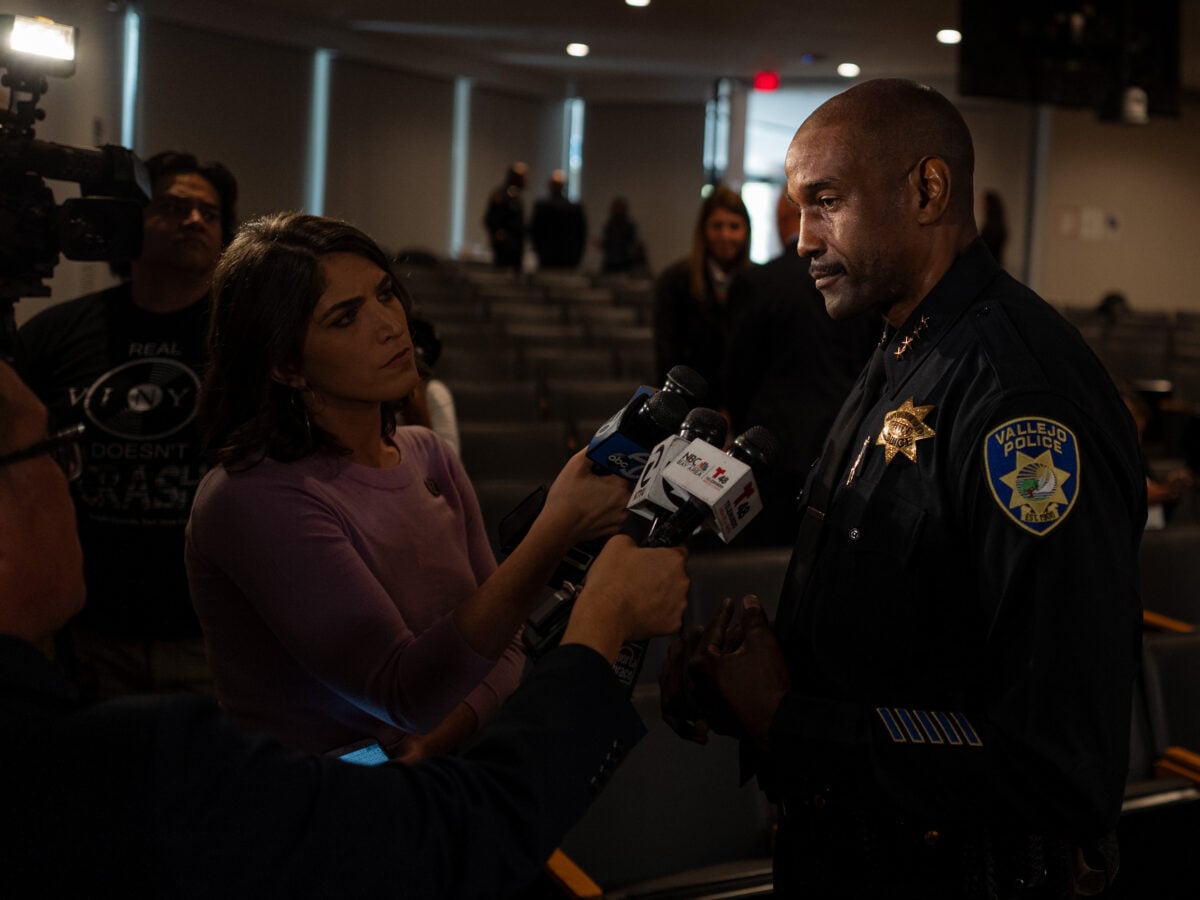

In recent years, the Vallejo Police Department has made headlines for gang-like rituals glorifying officers who kill in the line of duty; the illegal destruction of evidence; and an inordinately high rate of police shootings, among other scandals.

But the deadly encounter between Mefferd and Callinan has remained covered up — until now.

That is partly because the Solano County Sheriff-Coroner’s Office ruled Mefferd’s death an accidental drug overdose. The decision has allowed local officials to keep the killing secret for nearly a decade despite state transparency laws mandating the release of records about deaths and serious injuries caused by officers.

To this day, the city of Vallejo has not publicly acknowledged Mefferd’s death, which went unnoticed at the time by the news media. His family wanted to sue the city, but several lawyers declined to take their case because official records labeled Mefferd’s death an accident, the family said. Vallejo has declined to disclose public records about the case despite an ongoing public records lawsuit brought by Open Vallejo in September 2021. The city maintains that Callinan did not seriously injure Mefferd or cause his death.

The Fairfield Police Department and Solano County District Attorney’s Office are also still withholding records related to the case. Last December, this newsroom filed a lawsuit against Solano County for records relating to Mefferd’s death, among other documents. The Solano County Sheriff’s Office disclosed the coroner’s report and dispatch records; on Friday, the agency disclosed an additional 43 pages of investigative records following months of negotiation between this newsroom and the County Counsel’s Office.

No agency has released the body camera footage, surveillance video, or interviews with Callinan and a witness at the crisis center, among other evidence referenced in sheriff’s records. Open Vallejo also used medical files, interviews with family members, and EMT documentation to reconstruct the events surrounding Mefferd’s death.

Callinan and spokespeople for the city of Vallejo did not respond to requests for comment. The Solano County Sheriff’s Office declined to comment.

As Mefferd’s family still waits for answers, three experts in forensic pathology who reviewed the facts of Mefferd’s case told Open Vallejo that they would have likely ruled his death a homicide.

Misclassifications like these are not uncommon. For years, incomplete death investigations and an understudied pathology field have led coroners and pathologists to classify many non-shooting police killings as accidental, undetermined, or natural deaths, forensic pathology experts told Open Vallejo.

New research shows many of these deaths might instead have been caused by a previously misunderstood “mechanism of death” caused by police: prone restraint cardiac arrest, or PRCA. The discovery may explain the sudden and deadly consequences of holding someone face down for more than a handful of seconds, a control technique used by law enforcement that the U.S. Department of Justice has for decades recognized as dangerous.

“This happens within minutes,” said Dr. Victor Weedn, former Chief Medical Examiner for the state of Maryland and the co-author of a July 2022 study on PRCA. “The heart will just flat stop.”

Weedn said he believes that PRCA caused Mefferd’s death — not the accidental drug overdose recorded on his autopsy.

“This is basic physiology that we should have thought about but didn’t,” Weedn said. “We have an explanation for these deaths that we didn’t have before.”

The impact of mislabeling homicides for decades is profound, experts say, because such rulings often limit the potential for lawsuits or further investigations into in-custody deaths.

“How are you going to get a district attorney to investigate something that’s called an accident or ‘undetermined’?” said Dr. Michael Freeman, Professor and Chair of Forensic and Legal Medicine at the Royal College of Physicians, which is based in London.

Records show the sheriff’s office closed Mefferd’s case roughly six months after his death and referred it to the district attorney’s office, which took no action. In response to a request for comment on this story, District Attorney Krishna Abrams said the investigation into Mefferd’s death was handled appropriately.

“If there is new and different credible evidence regarding the cause or manner of Mr. Mefferd’s death, our office will re-open the investigation into this matter,” she wrote in an email to Open Vallejo on Sunday.

Over the past 20 years, the Solano County Sheriff’s Office has found that five men died accidentally during encounters with Vallejo police, including Mefferd. Four were held in prone restraint in the moments before they died. Four were Tased while struggling with officers.

Each of the victims, all of them men of color, were unarmed.

The Vallejo officers involved in their deaths did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

‘Get him off his stomach’

On the way to the Solano County crisis center, Mefferd allegedly became “uncooperative and agitated,” an official for the Solano County Sheriff’s Office wrote in a public records denial letter to Open Vallejo.

Reports differ on what happened next, but after exiting Callinan’s police cruiser, Mefferd fell to the ground — “flat on his face,” according to a source with knowledge of the matter, who reviewed body camera footage after the incident. The source said Callinan’s jacket partially obstructed his body camera, making it difficult to determine what caused Mefferd’s fall. The person spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the investigation.

Mefferd was handcuffed and should have been rapidly flipped on his side and medically assessed, according to guidance from the U.S. Department of Justice.

“As soon as the suspect is handcuffed, get him off his stomach,” reads a 1995 U.S. DOJ bulletin on how to reduce deaths in custody.

Instead, Callinan got on top of Mefferd, the source said.

“He sat on him with his whole body weight,” the source told Open Vallejo. “He sat on him for 10 minutes.”

In a January letter declining to release records in the case, Assistant City Attorney Katelyn Knight said Callinan did not use force against Mefferd. Instead, “at one point the subject spun, causing himself and the officer to fall to the ground, and the officer struggled with the subject and attempted to pull him to his feet,” Knight wrote.

Knight’s letter did not mention that Mefferd was held in a prone restraint.

A generally well-liked and affable officer, Callinan joined the Vallejo Police Department in 2016 after serving eight years in nearby San Pablo, Calif.

When, at some point during the incident, Mefferd’s body went limp, Callinan appeared clueless as to what to do, and panicked, the source said. Instead of performing a medical assessment, Callinan called the crisis center for help. No one came out of the building.

At least two people called law enforcement during the incident, communications logs obtained by Open Vallejo show. One of them was Callinan.

But instead of dialing 911, the officer — still sitting on Mefferd — Googled the Fairfield Police Department before calling the agency’s non-emergency line, the source said. Callinan likely “got caught up in their phone tree,” wasting crucial seconds, they added.

“If someone is struggling, and they’re facedown and they suddenly go limp, the officer has to change what they’re doing,” said Seth Stoughton, a law professor at the University of South Carolina who testified as a police standards expert for the prosecution in the trial of Derek Chauvin, the officer who was convicted of murdering George Floyd. “You can’t just leave the person there and wait for the paramedics. That’s completely unacceptable.”

Roughly five minutes past midnight, a Fairfield police dispatcher answered Callinan’s call. “VPD has one on the ground combative,” the call log reads.

One minute later, law enforcement answered the call from a person at the crisis center. The call logs reference a Vallejo officer “fighting with a subject.”

Although Callinan told Solano County investigators that Mefferd was conscious for several minutes after he fell, and the notes from the call logs suggest Callinan and Mefferd were involved in a physical altercation, the confidential source said Mefferd did not appear combative at all. In fact, they do not remember hearing Mefferd struggle — or even speak — based on their review of the body camera footage.

“It wasn’t like a big fight on the ground,” the source said. “Callinan got on top of him, and that was pretty much the end.”

All Vallejo officers are trained to administer emergency first aid and should initiate medical aid when appropriate, including CPR, according to department policy. But when Mefferd failed to rouse, Callinan did not request an ambulance or immediately begin resuscitation efforts, records indicate. Instead, he requested police backup.

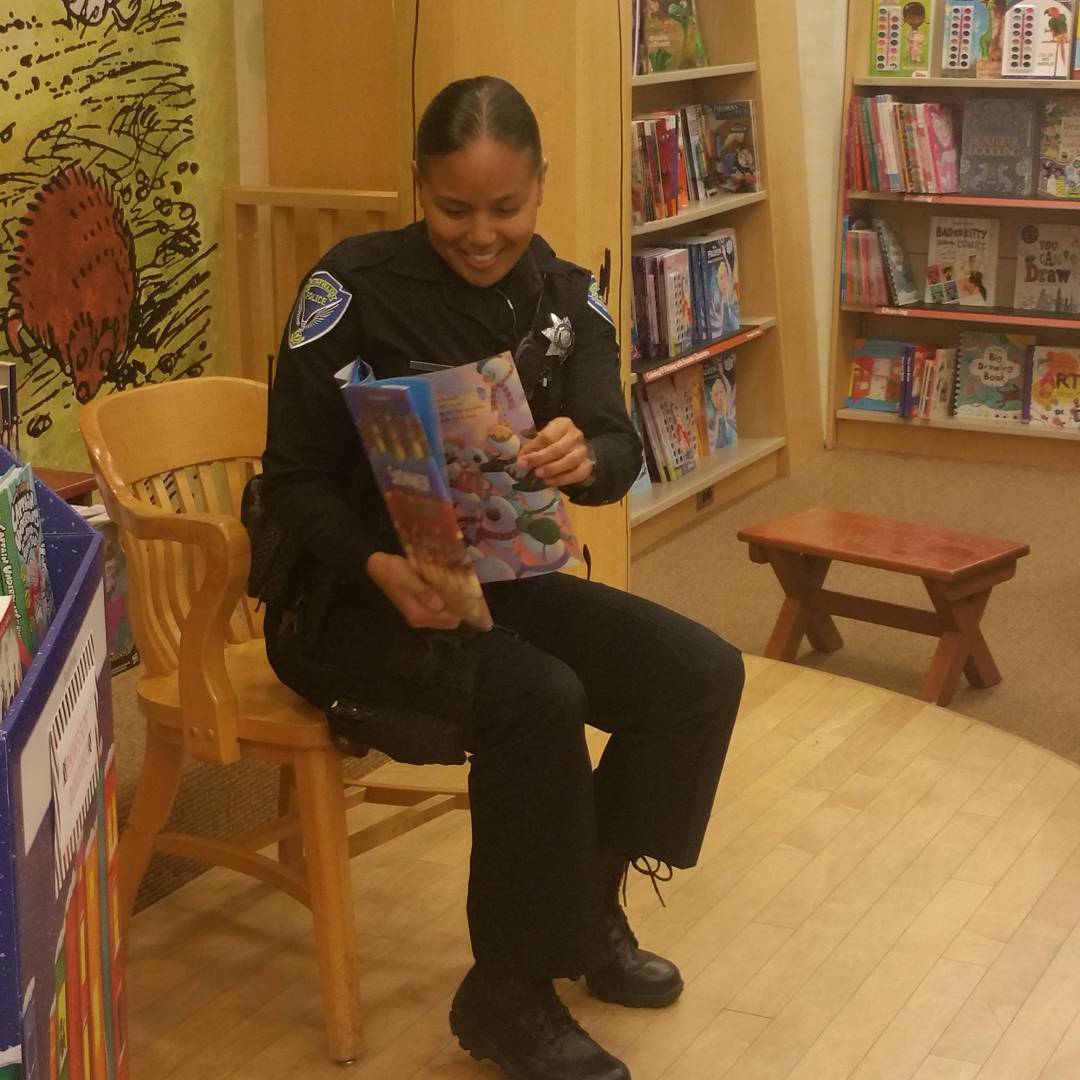

Two Fairfield officers arrived on the scene four minutes after the initial phone call, records show. They found Mefferd face down, still in handcuffs, and unresponsive.

A Fairfield officer, Camille Langi, quickly noticed Mefferd’s state, the source said. “She told him to get off the subject and suggested CPR,” they said. Records show when officers rolled Mefferd on his back, he had stopped breathing. Langi did not respond to requests for comment.

A Medic Ambulance report obtained by Open Vallejo found that officers first started CPR at 11 minutes past midnight. Langi provided chest compressions while Callinan held Mefferd’s head, sheriff’s records show.

A Fairfield police spokesperson said the agency’s officers performed CPR for several minutes until medical personnel took over. “Our involvement was limited only to the life-saving measures employed by our officers upon arriving at the scene,” wrote Jennifer Brantley. “Our department has absolutely nothing to hide.”

The confidential source said that Callinan was never disciplined in connection with the incident. The day after Mefferd’s death, Callinan filed a state workers’ compensation claim, according to confidential records obtained by Open Vallejo. He wrote that he bruised his right knee on the pavement while performing CPR that night, records show.

Because Callinan was a recent recruit, the city of Vallejo could have released him from employment without the lengthy police termination process that protects officers who have been with the department for at least one year. Instead, the new officer received a positive performance evaluation roughly two months after Mefferd’s death, records show. In 2022, he was promoted to sergeant.

The science behind accidental deaths

Excluding police shootings, between 2005 and 2022, an average of 42 people have died each year while in the process of being arrested by California law enforcement, an Open Vallejo analysis of California Department of Justice data shows.

Of the more than 700 deaths, 44 percent were ruled accidents, a third were listed as pending investigation, and just 5 percent were ruled homicides. Experts say many of the accidental deaths are likely misclassified homicides; more than half of U.S. police killings since 1980 have gone unreported in the National Vital Statistics System, according to a 2021 study published in the medical journal The Lancet.

A recent investigation published by the Associated Press, the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, and PBS FRONTLINE found that the police use of so-called less-lethal force options resulted in at least 1,036 deaths across the country from 2012 through 2021. Prone restraint and Tasers were the most common types of force among the identified cases, the investigation found.

Several academic papers, often backed by Taser manufacturer AXON Inc., have concluded that Tasers and prone restraint are safe, but a growing body of research suggests both techniques can be lethal. AXON asserts that all but a small fraction of Taser deployments result in no serious injury; in 2006 the company successfully sued a pathologist for listing their devices as a cause of death. The company declined to comment.

While research shows that Tasers can alter a person’s heartbeat and cause cardiac arrest, restraining a person face down has been known for decades to restrict breathing.

“Individuals must never be placed in the prone position when restrained,” a 2002 investigation into the deaths of people with mental illness by the advocacy group Disability Rights California found. “Prone is a hazardous and potentially lethal restraint position.”

The same year, the National Association of EMS Physicians denounced the use of prone restraint against agitated subjects.

Prone restraint is illegal across all state systems in Ohio and in schools in more than 30 states; earlier this year, the California State Senate approved a bill that would ban the practice in California schools. And while a 2021 California law banned peace officers from using techniques that present “a substantial risk of positional asphyxia,” no state law specifically forbids an officer from holding a handcuffed person face down.

Deaths caused by police restraints “may be classified as Homicide,” according to guidelines by the National Association of Medical Examiners, but homicide rulings in non-firearm deaths in custody remain rare in California, according to state DOJ data.

In part, that is because for decades, forensic pathologists — the doctors tasked with examining people who die suddenly or violently — struggled to find enough evidence to demonstrate the true physiological cause behind prone restraint deaths, according to experts. The lack of clarity has led some officials and researchers to seek out other explanations, including the controversial diagnosis of “excited delirium.”

“If you believe in restraint asphyxia, then you’re thinking the police did it. If you believe in excited delirium, then that’s kind of an argument that the police, it wasn’t basically their fault,” said Weedn, the former Chief Medical Examiner for Maryland. “So, you could say that this is a social view on which one you tended to prefer.”

Either way, Weedn said, findings often have to be made without clear-cut evidence of the exact mechanism of death.

According to Weedn’s research, published in the Journal of Forensic Science in 2022, most prone restraint deaths result not from a lack of oxygen, but from the inability to exhale enough carbon dioxide, which creates a buildup of acid in the bloodstream.

“It’s too much CO2 that you need to blow off,” Weedn said. “The buildup happens very rapidly, and your heart will just stop beating, just suddenly stop.”

While Weedn has cited prone restraint cardiac arrest to establish a death as a homicide, many other cases remain classified as accidental deaths.

“We believe most arrest-related deaths are due to homicide PRCA,” Weedn said. “But it’s still a new concept to a lot of people.”

George Floyd, for example, likely died of prone restraint cardiac arrest, Weedn said.

The medical examiner who made a final ruling on Floyd’s death, Dr. Andrew M. Baker, found that he died of “cardiopulmonary arrest complicating law enforcement subdual, restraint, and neck compression.” In other words, Floyd’s heart and lungs stopped functioning as Chauvin restrained him by kneeling on his neck.

However, Weedn points out that the exact mechanism of how Floyd’s heart stopped is not described in his autopsy report.

“What he really says is, ‘We think he died of this, but there’s no real evidence to say that’,” Weedn said. “Now, I believe we’re on the right path, and I think we’re going to have more and more evidence to show it.”

Baker declined to comment.

Weedn said PRCA could also help explain thousands of deaths allegedly caused by excited delirium, a diagnosis long used to justify deaths during police stops that is now banned in California and not recognized by the American Medical Association.

A 2020 study in the journal Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology found no evidence that excited delirium occurred without the presence of law enforcement restraints and found a direct correlation between the degree of restraint and risk of death.

“Excited delirium just basically says it’s not your fault — doesn’t matter what you did to them,” Freeman, a co-author on the study, said. “All we have to do is say, ‘We’ll just call it excited delirium, because excited delirium is what you call it when somebody dies in prone restraint while in custody.’”

The police and the pathologist

On the day of Mefferd’s death, Deputy Coroner Sgt. Corey McLean had a conversation with a sheriff’s deputy detective that would change the course of the investigation.

McLean had received a report about a death in custody and a “physical confrontation with the police,” according to the death investigation report he authored. He headed to the North Bay Medical Center in Fairfield to inspect Mefferd’s body and prepare his transport to the morgue. The sergeant had been with the Solano County Sheriff’s Office for nearly 20 years.

At North Bay, McLean documented several cuts and bruises on Mefferd’s knees, face, and buttock, as well as evidence of “struggles while wearing handcuffs,” according to his report.

Then, he called Courtney Mefferd. McLean told Courtney that her uncle had been in a confrontation with the police and that he had died shortly after.

McLean’s summary of the incident, however, dramatically shifted after he spoke with Det. Ronnie Sefried, who according to McLean’s report was present when investigators interviewed Callinan about the incident.

“The initial information I had was that the decedent had been in a physical confrontation,” McLean wrote under a 9 a.m. entry from the day Mefferd died. “I later learned,” McLean continued, “that the report of a physical confrontation with the police was unfounded.”

The investigator provided no evidence for this claim other than the summary from Sefried.

Sefried said Mefferd stumbled after exiting the car, and that Callinan “went down on one knee while the other knee was bent and resting against the decedent,” the coroner’s deputy wrote in his report.

“Ofc. Callinan never had his body weight on the decedent,” McLean’s summary continued. The summary makes no mention of the multiple reports of a physical confrontation documented in Fairfield police and Solano sheriff call logs.

McLean noted that Sefried viewed Ofc. Callinan’s body camera footage and although it was partially obscured by his cold weather clothes, “the visible footage substantiated Ofc. Callinan’s statement.”

McLean declined to comment. Sefried did not respond to requests for comment.

Callinan’s own statement about the incident has never been made public. Vallejo Police Det. Mathew Mustard, who in 2021 illegally destroyed evidence in multiple police killings with the approval of Assistant City Attorney Knight, authored a report summarizing Callinan’s interview with investigators. The city of Vallejo continues to withhold Mustard’s report along with the audio and video recordings of the interview.

After talking with Sefried, McLean appeared to stop his investigation altogether. The next entry in McLean’s report, detailed to the hour until then, is dated five days later. “The decedent was released to Skyview Memorial Lawn for final disposition,” McLean wrote.

Mefferd’s autopsy repeated language similar to McLean’s report. The pathologist wrote that Mefferd had “stumbled” while exiting Callinan’s car, “losing consciousness minutes later.” The autopsy, however, does not mention that Mefferd was restrained in the prone position, with an officer on top of him, shortly before he died.

McLean’s report gives no indication that he personally viewed the body camera footage or other surveillance videos sought by investigators. According to his report, McClean did not speak to any witnesses from the Solano County Crisis Center.

“You hear that somebody spent their very last minutes struggling, being assaulted physically, during a restraint, with lots of injuries to show for, and you don’t follow it up? You don’t get further information about what actually happened? You don’t demand to see the body cam footage? You just go along with it?” Freeman said. “What you have is a lack of complete investigation.”

‘Our mistakes are simply buried’

Bodies tell an incomplete story of life and death.

In some cases, the signs pointing to the cause of one’s death are few and unspecific, according to experts. When that is the case, pathologists must consider the circumstances in which someone died, along with autopsy and toxicology results, to determine the most probable cause of the death.

In California, forensic pathologists often have to rely on law enforcement for that critical information, making diagnoses difficult.

“We take the best info we got,” said Weedn. And sometimes, that information is wrong.

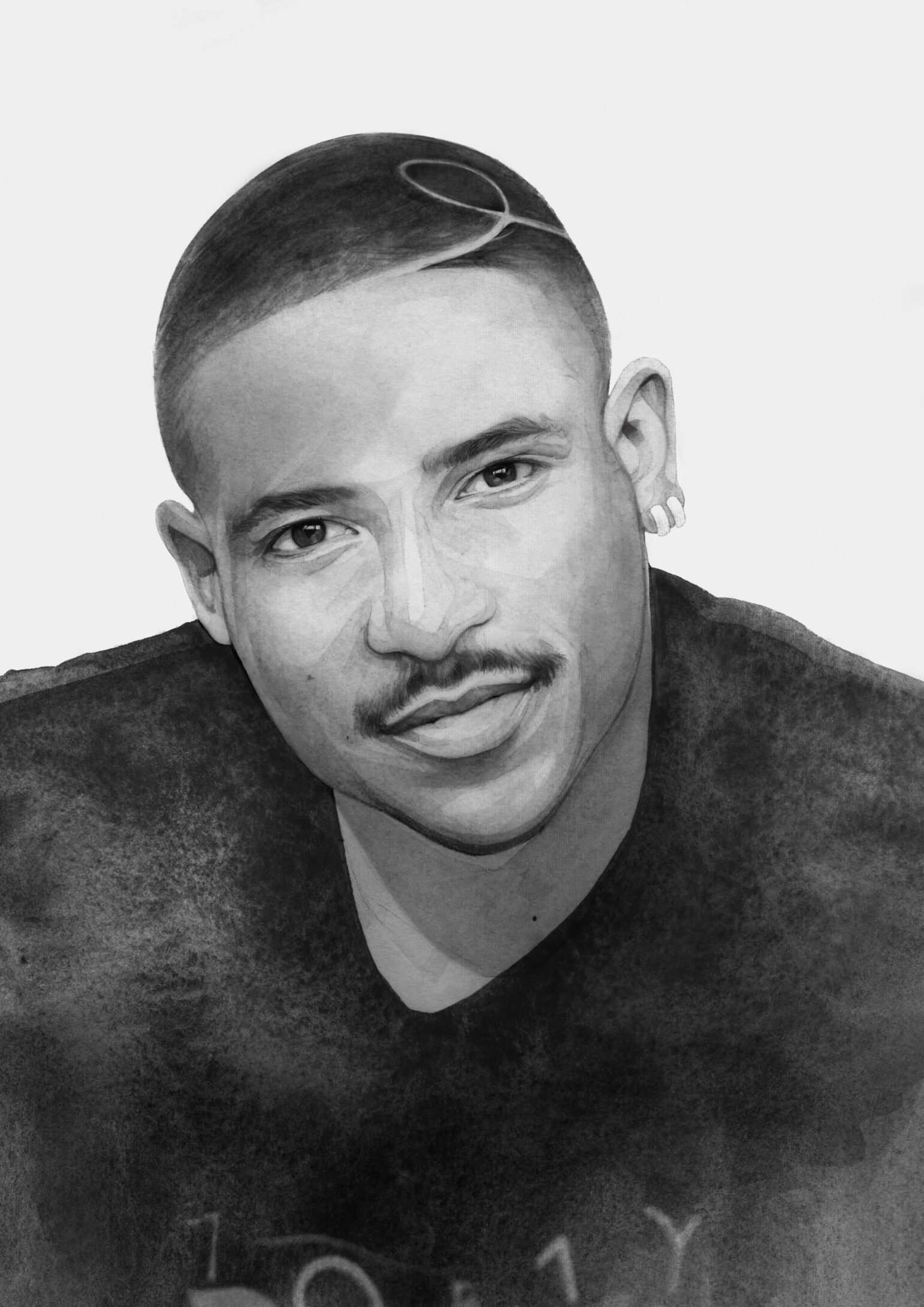

Andrew Lamar Washington’s cause and manner of death, for example, were based on an erroneous claim by Vallejo Ofc. Jeremie Patzer that he Tased the young man “four to five times.” Coroner records make no mention of the Taser’s log, collected by Vallejo police, which shows Washington was instead shocked 17 times for an almost continuous 2 minutes and 54 seconds.

Complicating matters is the fact that California is one of just a handful of states in which most local sheriffs also serve as coroners, giving them ultimate authority over death investigations. While California requires its few medical examiners to be licensed physicians specialized in pathology, there is no such provision for coroners, who are typically elected.

Experts have criticized the system for more than a decade. They maintain that only independent medical examiners, who are doctors, should be allowed to review and rule on the cause and manner of sudden deaths. Sheriffs who assume the role of coroner misclassify police killings at a higher rate than departments where the roles are separate, according to a 2022 study by researchers at the University of Southern California.

“If you have a case where there’s a concern that law enforcement has something to do with the death, then you have a potential conflict of interest,” Weedn said.

The sheriff-coroner model can impose other, practical limitations on the scope of a pathologist’s review, experts say. In a well-run death investigation, pathologists and investigators review evidence such as body camera footage, surveillance videos, and police and medical reports. But in California, many pathologists have little control over how evidence is gathered for the autopsy and death investigation.

“If you don’t do a good investigation in the first place, then you screwed up,” Weedn said. “Unfortunately, a lot of our mistakes are simply buried — so they don’t come to light.”

According to coroner’s records obtained by Open Vallejo, this is what Dr. Venus Azar, a contract pathologist for the Solano County Coroner’s Office, knew when she completed Mefferd’s autopsy on the afternoon of the day he died:

• He had blunt force trauma to the knees, torso, arms, and face, including three contusions on his head — one of them wider than a softball. But the trauma was not lethal, Azar found.

• He had broken ribs, which might have been from CPR, Azar noted.

• He had a 4-inch bruise on his right buttock.

• He had methamphetamine in his blood, in a concentration that was on the lower end of the potentially toxic range, according to his toxicology report.

• He had been under medical observation for close to eight hours, until just before his death.

But Mefferd’s medical records show his doctor deemed his methamphetamine diagnosis “uncomplicated,” and that Mefferd’s hallucinations and dry mouth may have been related to alcohol withdrawal.

Azar did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Mefferd’s niece Courtney told Open Vallejo that she saw no bruises or marks on her uncle when she was with him earlier that day.

“There’s no reason for any trauma at all, except for this incident," Weedn said, noting that even absent a struggle, “I really think we are talking about PRCA.”

Ultimately, Azar made a judgment call based on the information she had: an inconsistent story of the circumstances of Mefferd’s final moments, given to her by the agency that responded to the scene of his death, and supported only with evidence its investigators gathered.

‘Get out of jail free card’

Solano County’s other four investigations into accidental Vallejo police deaths in custody presented similar shortcomings as Mefferd’s.

In four of the five cases, death investigators did not document reviewing surveillance videos or other footage, according to public records obtained by Open Vallejo. Only one pathologist, who investigated the 2010 death of Michael Todd White, reviewed video recordings of interviews with officers and other first responders, among other records. In just two cases, deputy coroners documented having read police reports.

Instead, pathologists relied on toxicology reports, conversations with law enforcement, and, in two instances, medical records from the doctors who tried to revive the victims.

“It doesn’t appear that there was a complete investigation in every one of these deaths,” Freeman said. “And then you have this get out of jail free card, where we don’t even have to call this a homicide. We can call this Martian flu. We can call this anything we want.”

The decision by the Solano County Sheriff-Coroner’s Office to rule those deaths accidental allowed officials in multiple jurisdictions to keep information about the cases hidden from the public — and even from the victims’ families — despite the documentation of physical injuries.

In 2019, California Senate Bill 1421 made police records involving uses of force that result in “great bodily injury” available to the public but did not define the term, referred to as GBI. In response to public records requests, some agencies, including Vallejo, adopted a narrow interpretation of GBIs. Vallejo ruled that none of the five in-custody deaths constituted a GBI, even when Tasers or prone restraint were used on the victims.

When Open Vallejo requested the cases, Vallejo officials declined to disclose them based on the claim that the deaths in custody did not constitute great bodily injuries. Last May, in response to the public records lawsuit this newsroom filed against the city of Vallejo in 2021, a Solano County judge ruled that police must disclose records if a person dies within 96 hours of being Tased while in custody.

The ruling forced Vallejo to disclose thousands of pages of investigative case files — including reports, interviews, and other records — but none from Mefferd’s case.

Policing standards experts who spoke to Open Vallejo said that prone restraint is a use of force, but officials in at least one jurisdiction disagree.

“The City has not reviewed any records to indicate that the Vallejo Officer used any force, let alone that a use of force that resulted in great bodily injury or death,” Fairfield responded through its city attorney. “Thus the records are not disclosable under SB 1421.”

The city of Vallejo reported Mefferd’s death to the California Department of Justice, as required by state law for any in-custody deaths.

In the city’s January letter, Assistant City Attorney Knight cited a report summarizing Mefferd’s injuries, but omitting the broken ribs and large contusions on his head and buttocks documented in the autopsy.

The letter did not acknowledge that Mefferd died during the encounter with Callinan.

To Mefferd’s family, the lack of accountability compounded the pain of his loss. His mother, sister, and niece, who live in Solano County, said they were not allowed to see Mefferd’s body before he was cremated.

“That’s the most disturbing part about this,” said Courtney Mefferd. “My uncle is gone and we never got to see his body. Where’s our closure?”

This article has been updated to reflect new records, released for the first time in response to a lawsuit by this newsroom, that show Callinan placed a call to the Solano County Crisis Center for help. It previously included a confidential source’s recollection that Callinan had called out to crisis center staff.

Geoffrey King and Anna Bauman contributed to this report.