Two days after quietly withdrawing his agency’s lawsuit against Vallejo, California Attorney General Rob Bonta said in his first public statement that a settlement reached Monday allows the ongoing policing reform effort to “move forward immediately, irrespective of court approval.”

The California Department of Justice abandoned the lawsuit following six months of resistance from Solano County Superior Court Judge Stephen Gizzi. The proposed reform agreement “remained unsigned by the court and therefore unenforceable,” according to a statement released Wednesday by the DOJ.

“We cannot afford to be complacent. The reforms laid out in the agreement are needed and necessary,” Bonta said in the statement. “It’s past time the people of Vallejo have a police department that listens and guarantees that their civil rights are protected.”

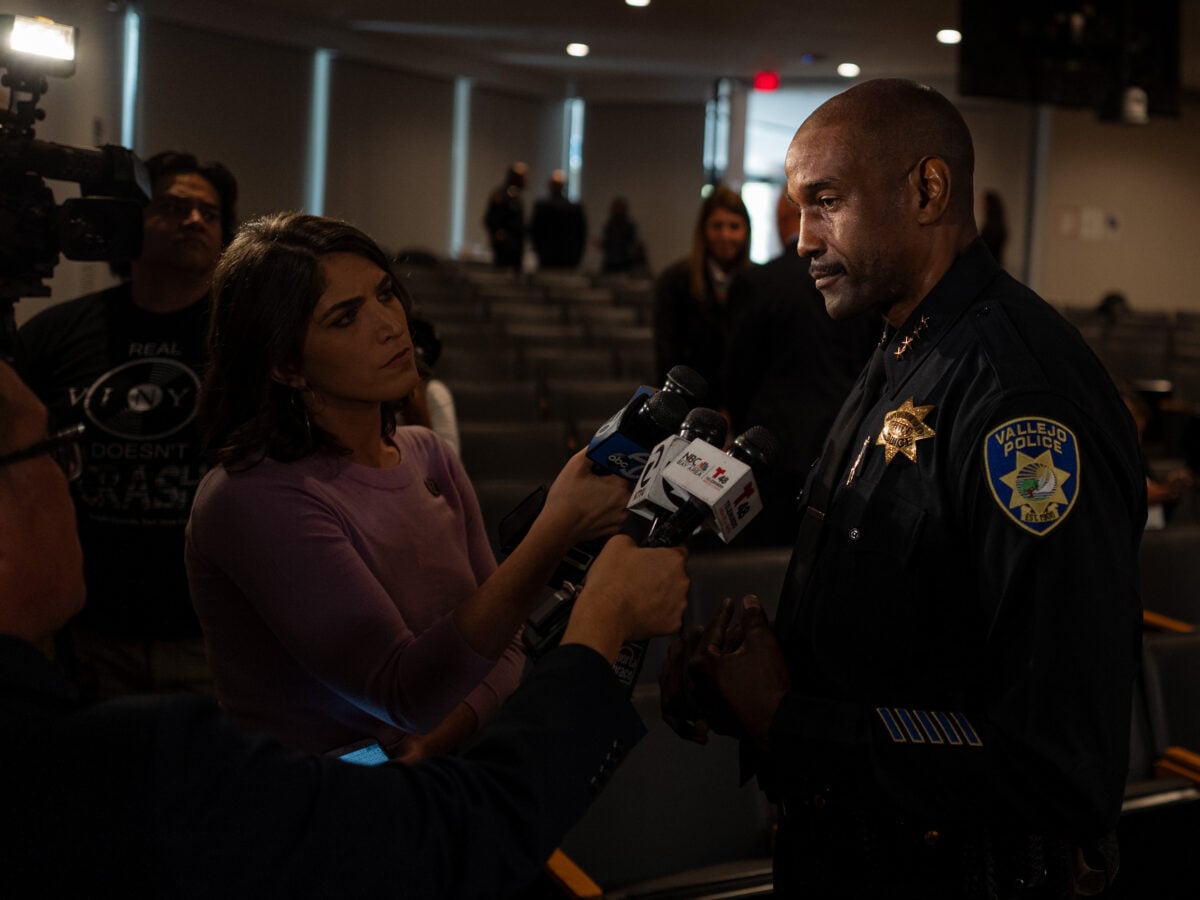

Alleging a pattern of excessive and unreasonable force, Bonta sued Vallejo and its police department last October. He asked Judge Gizzi to sign a stipulated judgment, an agreement between the state DOJ and the city that outlined a comprehensive set of police reforms. The judge, however, indicated in court filings that he would likely reject all or some of the proposal.

In a November court order, Judge Gizzi questioned the court’s authority over the case and listed concerns about specific terms of the proposed agreement, ordering the parties to show him why he should sign it.

The judge’s response is “unusual,” said David Alan Sklansky, a Stanford law professor and co-director of Stanford’s Criminal Justice Center. The attorney general has established consent decrees with law enforcement agencies elsewhere in California, including the Kern County Sheriff’s Office and Bakersfield Police Department, according to the agency. Sklansky said he was not familiar with another case in which a judge rejected a consent decree, especially one already agreed upon by both parties, on the grounds cited by Judge Gizzi.

On Tuesday, rather than move forward with its attempt to seek judicial oversight for the reform plan, the state justice department asked Gizzi to dismiss the entire case, prompting disappointment and confusion among many in the community.

Melissa Nold, a civil rights attorney in Vallejo, said in a Facebook post that Bonta’s decision was “a failure the Attorney General didn’t even bother to explain in any formal way to our community.”

“Imagine getting the opportunity to drop the hammer on Vallejo, and create meaningful, transformative change, and as soon as you catch a glimmer of opposition or inquiry you run away with your tail between your legs,” she wrote in the post.

Sklansky said the state DOJ could have tried harder to convince Judge Gizzi to sign the agreement or even appealed his order to a higher court. However, he said, the agency may have realized the Solano County judge’s involvement “isn’t going to be helping us — and he doesn’t seem to want to be involved anyways.”

“With this particular judge, they may have just decided that the reform process would move forward more smoothly without the judge’s involvement,” Sklansky said.

The 60-page settlement agreement includes reforms nearly identical to those in the stipulated judgment, which aim to “bring Vallejo into alignment with contemporary best practices and ensure constitutional policing,” according to the DOJ.

The parties selected Jensen Hughes, a global risk management firm, to serve as a third-party evaluator. The firm will provide expertise and consulting, help resolve disputes, and assess the city’s progress toward achieving the goals by conducting audits and reviews, according to the settlement agreement.

The DOJ hired the same firm in 2020 when it first launched a three-year collaborative reform agreement with Vallejo due to the “number and nature” of the city’s police shootings. But Vallejo failed to implement more than half of 45 DOJ-endorsed recommendations, prompting the DOJ’s October 2023 lawsuit.

The settlement signed Monday requires Vallejo police to complete the remainder of those recommendations, in addition to more than 100 changes related to the department’s policies, training, and practices regarding use of force, bias-free policing, community partnerships, response to people experiencing mental health crises, complaint intake and investigations, stops and searches, and more.

Sklansky said the success of the agreement will depend partly on the Vallejo Police Department’s commitment to the reform process. He said court involvement in such cases typically provides more accountability because a judge has more “clout” than an evaluator to enforce the terms of the agreement.

“When the reform process hits a snag, and reform processes always hit snags,” he said, “it may be harder to bring that party in line without the ability to go to the judge.”

Under the settlement agreement, Jensen Hughes will create an annual oversight and reform plan, with input from Vallejo police and approval from the DOJ, which will include specific implementation deadlines, schedules, and timelines. The firm will also issue an annual, public report detailing Vallejo’s progress.

The DOJ will oversee Jensen Hughes and ultimately decide whether Vallejo is in substantial compliance with its obligations, according to the settlement. Should Vallejo miss deadlines or fail to implement changes, the state agency may seek to enforce the agreement by filing a lawsuit in Alameda County Superior Court.

For example, the DOJ could enforce a specific obligation through the courts, file a lawsuit alleging a pattern or practice of unconstitutional conduct, or pursue “any other judicial proceedings that DOJ deems appropriate,” according to the settlement.

Vallejo anticipates completing the reforms within five years, although the agreement will remain in place “until the terms are met,” according to the DOJ. The city and state DOJ may agree to terminate the contract in three years if Vallejo has reached and maintained substantial compliance for at least a year.

This article has been updated to include comment from Stanford law professor David Alan Sklansky.