In 2021, then-Vallejo Police Chief Shawny Williams enlisted a Chicago-based technology company to scrutinize his officers’ body camera recordings using artificial intelligence.

The decision drew the ire of Vallejo’s powerful police union, which argued it should have been consulted first. Within a year, Vallejo’s reform-minded police chief would be gone, and his former deputy chief, Jason Ta, left in charge.

Now, an employee at the company, which is called Truleo, has said in a series of direct messages to a civil rights lawyer that Ta canceled the contract after Truleo’s software began to surface unprofessional behavior by officers, leading to pushback within the department, records obtained by Open Vallejo show. The messages were sent in January to local attorney Melissa Nold, who represents plaintiffs in multiple lawsuits against the city.

In a Friday interview, Truleo CEO and co-founder Anthony Tassone declined to comment on the Twitter messages but voiced concerns over police accountability in Vallejo.

“By canceling they essentially ceded to union pressure. And by doing that, they’ve gone back to status quo, which is to review practically none of it,” Tassone said about the city’s body camera videos.

“Chiefs should stop pretending they don’t know what’s on the videos. If they want to know, they can know,” Tassone said. “Our job is to increase civilian awareness and let every elected official know that less than one percent of these body cameras are ever being reviewed. And that’s not acceptable.”

Spokespeople for the city did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Ta became chief and shut it down’

Truleo uses natural language processing to automatically transcribe audio of officers’ body camera footage. The software then attributes a professionalism score to each interaction and identifies any potentially serious incidents for supervisor review. If officers remain polite, give clear direction, and provide explanations for their decisions, they are likely to receive a high professionalism score.

Since it was established two years ago, the company has partnered with the FBI National Academy Associates and the California Police Chiefs Association.

In November 2020, the Vallejo Police Department found that Ofc. Colin Eaton violated department policies relating to respectful treatment of members of the public and the use of profane or derogatory language during this April 20, 2020 interaction with a person he detained. The department subsequently found in March 2021 that Eaton’s conduct also violated use of force and safety standards.

Under its contract with the city, Truleo was to produce regular reports highlighting interactions that received high and low professionalism scores from the software. That meant that each body camera video the department generated would be reviewed and analyzed for signs of problematic officer behavior.

“This was unpopular with the patrol officers. They did a vote of no confidence against the chief,” a message from Truleo’s official Twitter account to Nold read.

As the city began working with Truleo, the Vallejo Police Officers’ Association held a vote of no-confidence in Williams, resulting in an overwhelming vote against him.

Then, on Jan. 28, 2022, attorneys for the union sent Williams a grievance and cease-and-desist notice in response to what they said was the city’s “unilateral implementation” of Truleo’s software, emails reviewed by Open Vallejo show. (The city of Vallejo did not disclose the grievance letter in response to a public records request filed by this newsroom.)

Months before, the union had similarly tried to halt the implementation of an interim police auditor on the basis that the city did not properly consult the union first. (The city council’s decision to establish an independent auditor was never implemented).

Williams responded by proposing a meet-and-confer session with union representatives, but the opposition persisted.

The Vallejo Police Officers’ Association did not respond to requests for comment.

“The Union is not fond of the idea of Truleo,” then-deputy chief Ta told a Truleo executive on a May 2022 phone call, according to an email memorializing the conversation sent to Ta following the call.

Ta, who oversaw the company’s work in Vallejo, continued to work with Truleo until September, when he stopped responding to the company’s emails for more than a month, records show.

By the end of October, a Truleo representative sent an email to Ta advising him to check the department’s Truleo account for “risk events” — potential instances of unprofessional conduct, uses of force, or violations of policy, for example — that had been flagged by the software but had yet to be reviewed by supervisors.

“I’ll check it out soon,” Ta answered. “Much happening. Hope I can touch in with you soon.”

Less than a week later, Ta had become the department’s new interim police chief. A month after that, he canceled the agreement with Truleo, records show.

“Chief Ta became chief and shut it down,” read one of the messages from Truleo’s Twitter account to Nold.

“I was really shocked that they reached out to me,” Nold told Open Vallejo in a Friday statement. “But I was thankful that they did, because it was another piece of the puzzle of corruption and coverups in Vallejo that the public needs to know about.”

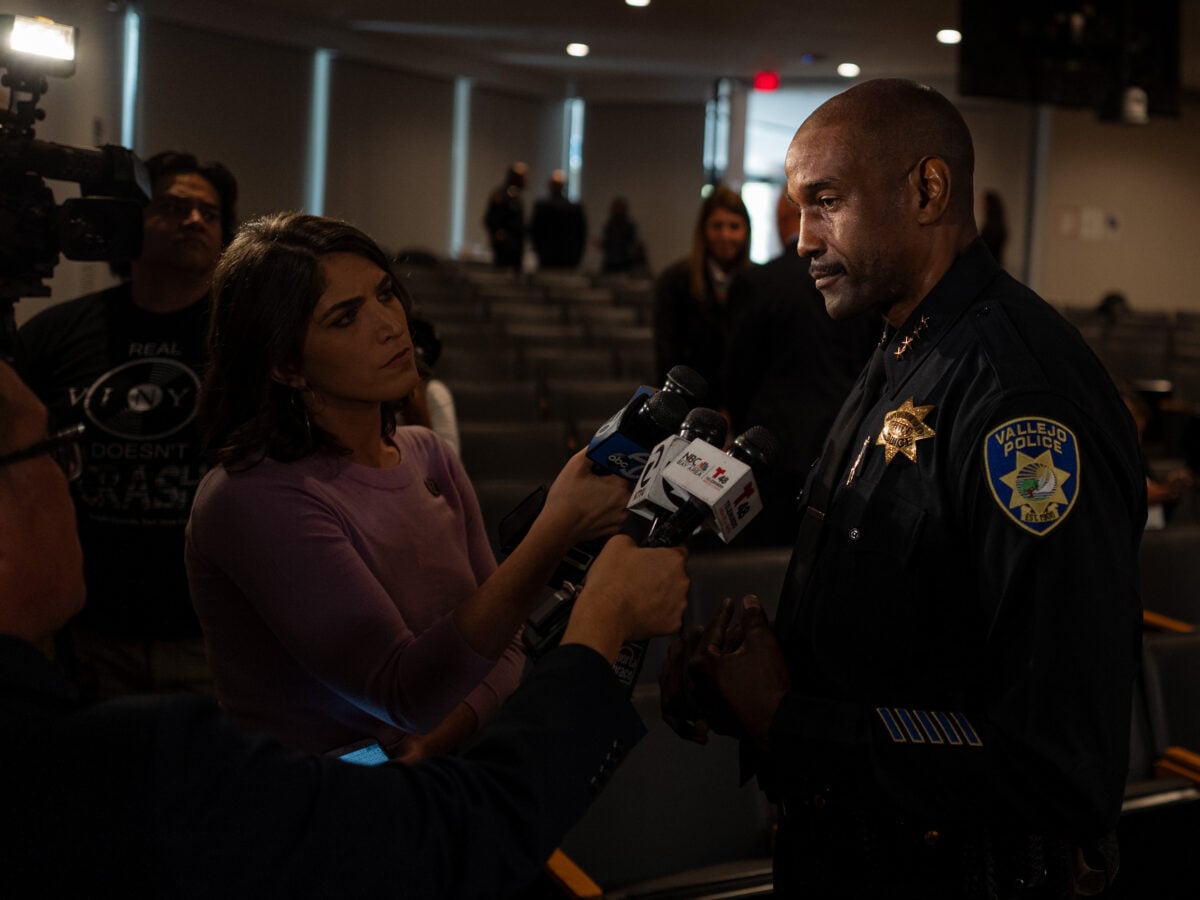

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Civil rights attorney Melissa Nold speaks during a rally against police violence on March 8, 2022 at Vallejo City Hall. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoVallejo reviews less than one percent of its body camera footage, according to Tassone — a figure he says applies to many departments.

“Chiefs around the country lack the courage to analyze 100% of their videos because they suspect a HUGE portion of the department is performing unprofessionally,” a message to Nold from Truleo’s Twitter account read.

According to a January 2022 Vallejo Police Department press release advertising the department’s partnership with Truleo, “In most cases, body-worn camera video is only reviewed during critical incidents, at times taking hours to analyze.”

Tassone said this is not the first time a police union has pushed back on its technology.

Earlier this year, the Seattle Police Officers Guild alleged that its police department had begun using the technology without informing officers. Along with the ACLU of Washington, the union expressed privacy concerns relating to civilian information recorded by body cameras. According to its website, Truleo can automatically redact information that could identify civilians.

The Vallejo and Seattle police departments are the only agencies to have ever canceled their contract with Truleo, Tassone said.

“And the difference is that Vallejo and Seattle didn’t sit down with their union and explain the benefits, and explain how this can help with coaching and officer wellness, and how they can surface and celebrate positive behavior,” Tassone said.

In the Bay Area city of Alameda, Calif., the police department saw a 30 percent decrease in unprofessional language used by officers, and a 36 percent drop in uses of force following the implementation of Truleo, according to a case study summarized on Trulio’s website.

But no such data is available for Vallejo.

“Chief Williams in Vallejo was not there long enough to allow the study,” Truleo wrote to Nold on Twitter.