Warning: this article contains a graphic description, and embedded video, of the killing of a minor.

Jared Huey laid down at the base of the cement wall blocking his escape, a dozen police officers on his tracks.

A Vallejo officer soon appeared through the tall grass; another raised a rifle over the wall next to Huey. He had nowhere left to run.

Obtained by Open Vallejo through a public records request

Jared Huey lies dead in the backyard corner where he was shot by Vallejo police on June 30, 2012. Eleven years ago this week, Ofc. Jeremy Huff shot Huey with a rifle from behind the cement wall. Ofc. Kevin Bartlett also fired. Credit: Obtained by Open Vallejo through a public records requestExactly what happened over the next ten seconds is disputed. One thing, however, is not: the officers, Jeremy Huff and Kevin Bartlett, fired 16 rounds at Huey, hitting him in the back, back of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and legs and arms, forensic reports obtained by Open Vallejo reveal. The bullets shattered both of Huey’s femurs and almost severed his right arm from his body. He was 17 years old.

The officers told investigators that Huey raised a revolver toward Huff, who was standing behind the cement wall. Yet two witnesses said they heard someone scream, “Don’t shoot,” and “No, no!” moments before Huey was shot, according to records reviewed by this newsroom. One of them specifically identified Huey as the person screaming.

A revolver was found near Huey, partially covered by layers of plant material, previously-undisclosed photographs obtained by Open Vallejo show.

Jared was courageous, and a skillful judo student, his father recalled — but he was also smart. He would not have pointed a gun at the police officers surrounding him, Michael Huey said. (A forensic analysis found an indentation on a cartridge inside the revolver, indicating someone may have, at some point, unsuccessfully attempted to fire it.)

Obtained by Open Vallejo through a public records request

Previously-undisclosed crime scene photos obtained by Open Vallejo show a revolver police said was found near Huey. The city claimed that Huey was holding the revolver toward officers at the time he was shot. Credit: Obtained by Open Vallejo through a public records requestThe same week, Vallejo police released information to the press erroneously claiming Huey was in his 20s and linking him to an alleged robbery from earlier that day, in potential violation of juvenile confidentiality laws, according to criminal justice experts who spoke to Open Vallejo. Authorities identified Huey by name, but kept those of the officers who killed him confidential for more than a year, until Huey’s father obtained their names through a civil rights lawsuit.

Now, the city of Vallejo is fighting to keep the investigation into Huey’s death a secret — and using laws aimed at protecting the reputations of minors to do it. Last month, in a public records lawsuit filed by this newsroom against Vallejo, a Solano County judge ruled that the city could continue to withhold records of police uses of force against minors.

Huff, Bartlett, and spokespeople for the city of Vallejo did not respond to requests for comment.

Vallejo Police Department

The Vallejo Police Department promoted Jeremy Huff to sergeant in 2017. He was promoted to lieutenant in 2022. Credit: Vallejo Police Department“This seems like a not-so-veiled attempt to keep police records from the public, and I suspect in cases involving juveniles because they are the kind of cases that could create the loudest public outcry,” said Delores Jones-Brown, a visiting professor at Howard University, professor emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the founding director of the John Jay Center on Race, Crime and Justice.

“I think that any issues related to confidentiality of the juvenile could be resolved by simply redacting the information,” Jones-Brown said. “Particularly in a place where there is a commitment to transparency.”

In the past five years, California legislators have enacted a series of transparency laws that have forced government agencies across the state to disclose certain types of police records for the first time. One of them, Senate Bill 1421, made records of police killings, sustained sexual misconduct by officers, and other serious uses of force available to the public.

Since then, police unions and law enforcement agencies around the state have fought to withhold these records using a range of legal arguments — among them, the idea that a welfare code section that made juvenile court records confidential allows police to keep secret the investigations into use of force against children.

“It’s very clear to me that this is an abuse,” said George Galvis, the co-founder and executive director of the Bay Area nonprofit Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice, which helps young leaders pass legislation to end youth criminalization.

“It’s really concerning that they’re abusing the spirit and intent of SB 1421 in this way,” said Galvis, whose nonprofit helped develop the law.

Yet in the past year, two California superior courts have interpreted the transparency law to exclude records of police violence against juveniles from disclosure.

“I can tell you that as one of the sponsors: that was not the intent. We would never have ever allowed that,” Galvis said.

‘A free pass on transparency’

State and federal laws have long restricted government agencies from publicly releasing information about juveniles’ interactions with the criminal justice system. The laws aim to protect young offenders from social stigma and reduce barriers to employment, housing, and higher education.

Those same protections, however, have come to shield police who use force on children from the scrutiny of state transparency laws.

“Juvenile records are subject to blanket protection against production,” Solano County Judge Stephen Gizzi wrote in a May ruling relating to Open Vallejo’s lawsuit.

The rule against disclosure applies even if the young person is deceased and no criminal charges are filed against them, the judge held.

“I do think that the ruling is an error and a mistake,” said David Loy, the legal director for the First Amendment Coalition, a public interest nonprofit that litigates cases relating to SB 1421 and other public records laws.

“The police should not get a free pass on transparency because they happen to commit a crime against a minor, or kill a minor, even if that killing is justifiable,” Loy said.

Judge Gizzi did not discuss whether the city may have waived juvenile protections in Huey’s case when divulging the boy’s name and alleged involvement in a crime.

“They’ve already made the name of the juvenile public. Question is whether that was legal — but having done that I don’t think they can turn around and say, ‘We can’t make it public now,’” Loy said.

“The laws that are designed to protect juveniles should not be twisted to conceal records about killing juveniles.”

Broad protections for police

The juvenile protections against public disclosure extend beyond cases like Huey’s, where the minor is the victim of police violence, according to Judge Gizzi’s May order.

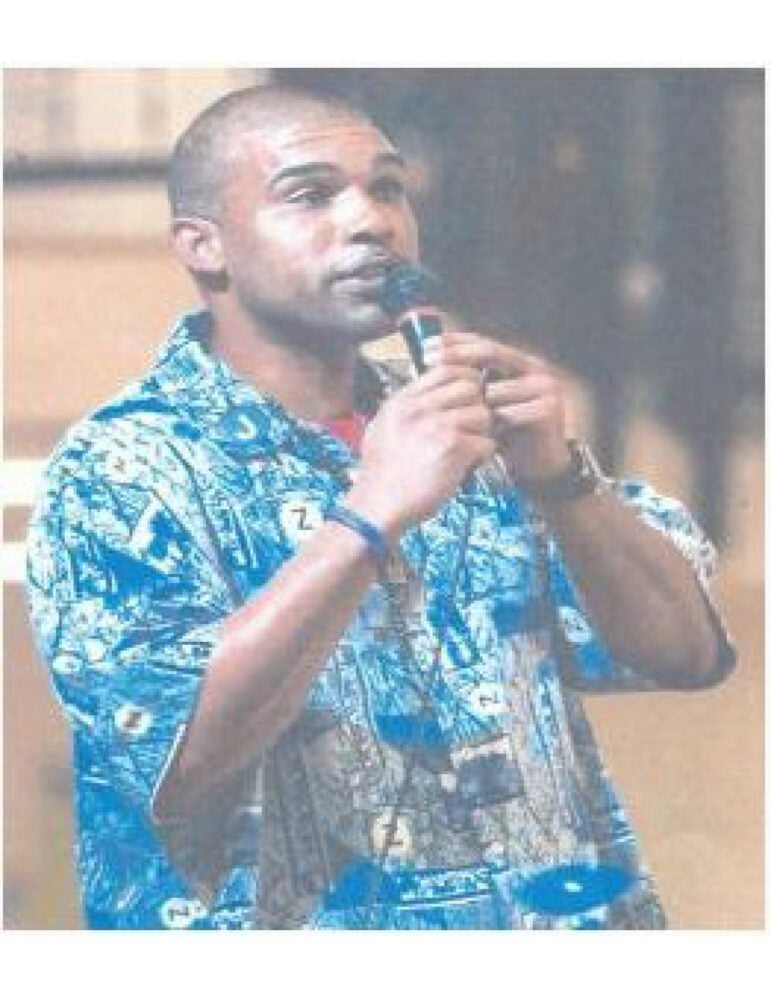

Guy Jerome Jarreau Jr., for example, was 34 when he was shot to death by Vallejo police officer Kent Tribble on Dec. 11, 2010. Tribble is a key figure in Vallejo’s “Badge of Honor” scandal, in which officers bend the tips of their star-shaped badges to mark fatal shootings.

Jarreau and some of his friends from Napa Valley College were filming an anti-violence video near Jarreau’s apartment, adjacent to an alley on Sonoma Blvd., when a person allegedly called police about a man brandishing a handgun, according to a Vallejo officer’s account summarized in a coroner’s report obtained by Open Vallejo.

The group dispersed as police arrived. Jarreau was standing in the alley steps away when Tribble fatally shot him in the chest. Jarreau’s mother alleged in a lawsuit that her son was holding a green cup, his hands above his head. The city denied that Jarreau had his hands up, claiming he was holding a firearm.

Police handcuffed multiple of Jarreau’s college friends, who were also witnesses, records reviewed by Open Vallejo show.

Tribble did not respond to a request for comment.

City officials did not disclose evidence supporting their claim that a handgun was found at the scene of the shooting, nor did they release audio of the call to 911. Witnesses said the camera used to record the anti-violence video may have captured at least part of the incident, but police did not release such footage.

In fact, Vallejo police have refused to disclose any records related to the shooting on the basis that at least one of the witnesses detained that day was a minor.

They also withheld reports from Jarreau’s family, according to his mother, Andrea Jarreau-Griffin.

“I was told, by the Vallejo Police Department, that I do not have the rights to a police report because I am not a ‘victim’,” Jarreau-Griffin wrote in a letter to then-President Barack Obama requesting an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice.

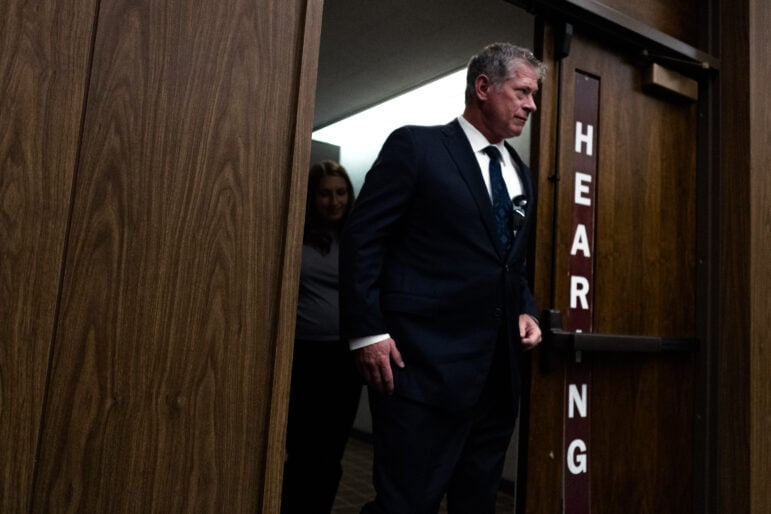

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Former Vallejo Police Lt. Kent Tribble arrives in Solano Superior Court to testify about his role in Vallejo’s “Badge of Honor” ritual on March 22, 2022 in Vallejo, Calif. He is accompanied by Assistant City Attorney Katelyn Knight. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoIn his ruling, Judge Gizzi declined to order that the city release the records in Jarreau’s case.

“That information gets concealed simply because there was a minor involved in the incident, I think that’s completely wrong,” said Jones-Brown, the professor emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Other experts agree. “The police killed an adult. Under SB 1421, those records must be disclosed, full stop,” said Loy. “SB 1421 has a clause that specifically allows the police to redact names of third parties, like witnesses or other participants in the incident who are not killed or not at issue.”

Experts also worried about the consequences such an interpretation of the law might have on police interactions with juveniles.

“One potential collateral consequence of that rule is to encourage police to cover for their actions by arresting juveniles who happen to be in the vicinity,” Loy said.

‘We’re going to have to address it’

Senate Bill 1421 allows agencies to redact portions of documents to preserve the identity of witnesses and remove “information of which disclosure is specifically prohibited by federal law or would cause an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy,” among other reasons.

Judge Gizzi, however, declined Open Vallejo’s request to redact the juvenile records instead of withholding them entirely.

Last year, San Francisco Superior Court Judge Curtis E. A. Karnow similarly found that the transparency law does not override juvenile confidentiality protections — and specifically ruled against redacting the records on the basis that juvenile case files are protected from production in their entirety, according to court records in a lawsuit brought against California’s Attorney General by KQED and the First Amendment Coalition. KQED’s lawyers in that case also represent Open Vallejo in its ongoing lawsuit against the city.

Experts who spoke to Open Vallejo noted that SB 1421 mandates that records be made available “notwithstanding any other law,” but Judge Karnow was not convinced that the provision overrode juvenile court protections.

“We still need to examine, as we did before the new law, the usual (traditional) exemptions. These have not been obliterated by SB 1421,” Judge Karnow wrote.

Galvis, whose nonprofit sponsored the law, disagreed. “That is just a clear example of them trying to rationalize the irrational and defend the indefensible,” he said, “It’s bullshit. And we’re going to have to address it through a trailer bill.”

KQED and FAC appealed the case, but the issues relating to juvenile records were not a subject of the appeal, according to Thomas R. Burke, one of Open Vallejo’s attorneys who represented KQED in its lawsuit against the state attorney general.

Sen. Nancy Skinner, who introduced SB 1421, did not respond to a request for comment.

“If anything, the public interest is even more compelling when the police are killing children,” Loy said. “They should be required to disclose the full story, not just the parts that they want the public to hear.”