For nearly four years, the Vallejo Police Department has patrolled the city with the help of drones, advanced surveillance tools that allow police to track people from above. To prevent their abuse, the department adopted a policy that requires the police chief or a designee to give written permission when officers put drones in the air.

But an Open Vallejo review of the 91 drone flights the department has logged between 2018 and December found no record that any individual flights had been authorized. Asked to produce such records last May, the department said it found none. Now, following inquiries by Open Vallejo, the department plans to weaken the policy, records obtained by this newsroom show.

In a July interview, Vallejo Police Chief Shawny Williams declined to answer questions about whether he has authorized any drone flights.

Instead, the chief said he believes the policy requires written authorization only in some situations, although legal experts who reviewed the policy expressed skepticism of his interpretation.

Vallejo Police Department Policy 607.4

Deployment of a [drone system] shall require written authorization of the Chief of Police or the authorized designee, depending on the type of mission.

Asked to clarify, the chief said that, “during exigent circumstances, a written authorization wouldn’t be mandated,” adding that drones can be deployed in “life or death” situations such as to find an active shooter or missing person, or to respond to a natural disaster.

The policy states, “Deployment of a [drone system] shall require written authorization of the Chief of Police or the authorized designee, depending on the type of mission.” It does not specify which type of mission would be exempt under Williams’ interpretation of its terms.

“[It] seems to me that the written authorization is required, and what changes depending on the circumstances is who needs to sign off,” Joanna Schwartz, a police policy expert and professor at the UCLA School of Law, said in an email.

In response to further questioning, Williams then offered an expansive interpretation of his powers as the city’s top law enforcement official.

“The drone program is authorized by the chief of police,” Williams told Open Vallejo.

The policy does not grant the chief discretion to pre-approve all flights, however.

Vallejo City Attorney Veronica Nebb declined to comment on the city’s interpretation of the policy, citing attorney-client privilege.

From “shall” to “should”

Vallejo’s drone policy was written by Lexipol, a company that develops policies and training materials for law enforcement. Agencies across the country rely on Lexipol drone policies nearly identical to Vallejo’s, a review by Open Vallejo found.

“Most times, it’s a cut-and-paste job,” said Mike Katz-Lacabe, research director for Oakland Privacy, an organization that monitors the use of surveillance technologies by local law enforcement. Other critics argue that Lexipol’s policies are vague, making it hard to tell when they are being violated.

Lexipol did not respond to a request for comment.

The drone policy assigns responsibility for drafting an authorization protocol to a “drone program coordinator,” noted Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a police surveillance expert and professor at the American University of Washington College of Law. Ferguson added that the policy has little meaning without that document.

But the department was unable to produce records demonstrating that it has written or implemented that protocol.

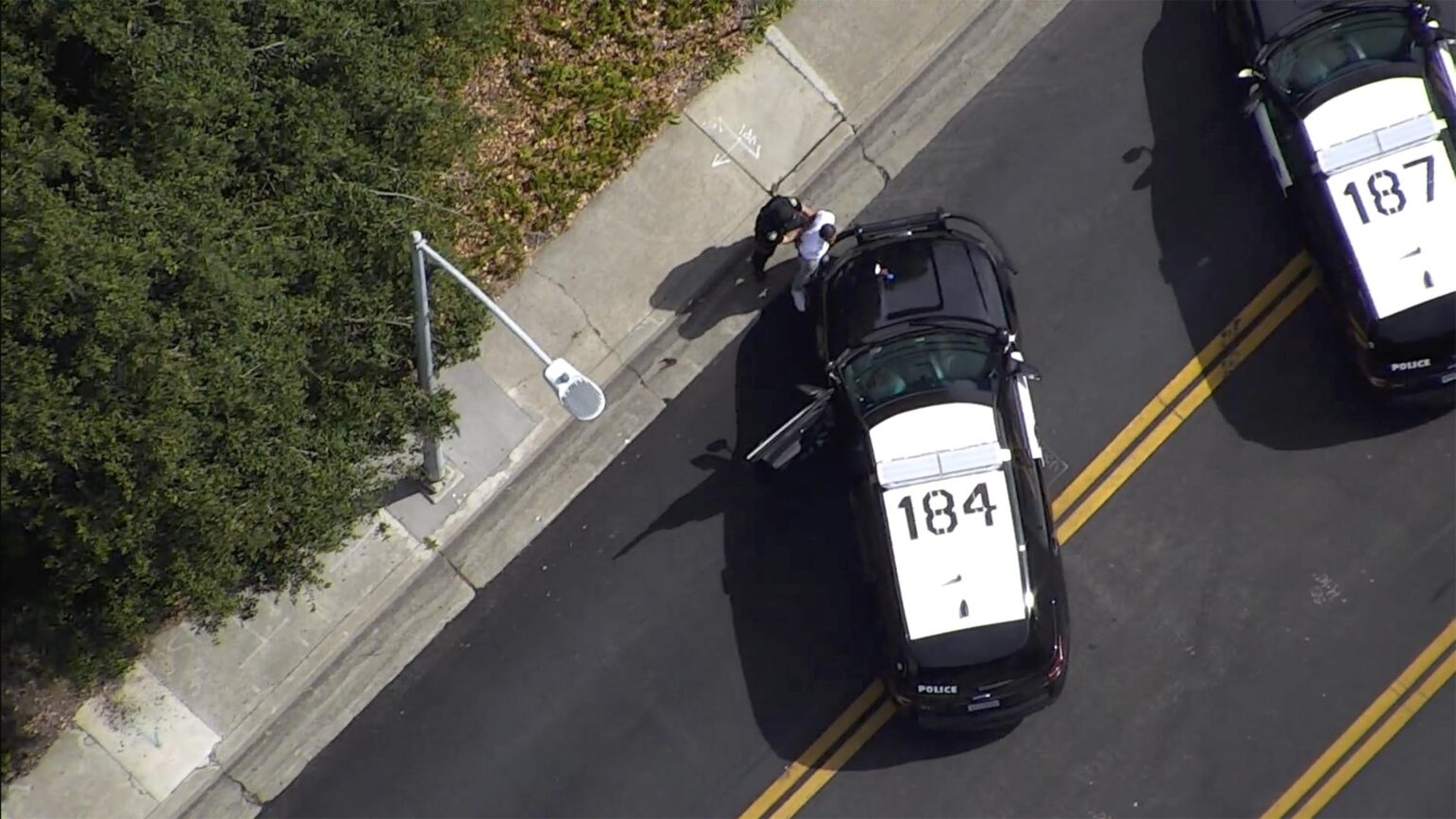

Noah Berger / Special to Open Vallejo

The Vallejo Police Department’s Emergency Services Unit vehicle is seen from an overhead drone on Sunday, Nov. 21, 2021. Credit: Noah Berger / Special to Open VallejoIn August, two weeks after Open Vallejo interviewed Williams about Vallejo’s drone program, the department released a new version of its flight logs listing the mission type for each launch. Missions fell into one of four categories: training, patrol, test flights, and “ESU,” an abbreviation for Emergency Services Unit, similar to a SWAT team. Since 2018, just nine of the 91 flights have fallen into the Emergency Services Unit category.

The day after releasing updated logs in August, the department announced it was reviewing its drone policies and expanding the drone program.

“As our program evolves, our priority remains streamlining the program and policies to increase transparency and provide our community with a better understanding of drone technology and public safety benefits,” the release read.

Months later, Open Vallejo again requested that city officials disclose individual drone flight authorizations. The city produced no such records. Instead, officials released four emails, sent on Oct. 19, in which Capt. Jason Potts appeared to authorize all future flights. The exchange also revealed the department’s plans to weaken the drone launch policy.

“We will have [the Professional Standards Division] change that shall get written authorization to should,” Potts wrote to other senior officers, who forwarded the email to several additional members of the command staff and drone team. The change in language from “shall” to “should” would allow officers to bypass the authorization requirement in at least some situations.

Potts then ended the email thread by asking officers to “continue to get supervisor approval before deploying [drones]” — even though the department has been unable to show such approvals have previously occurred.

The department has not yet changed its drone policy, which still requires authorizations for drone launches. However, the city provided no evidence that it had individually approved any of the at least 11 drone launches that have occurred since the email exchange.

Williams was not included in the email thread. He did not respond to subsequent requests for comment.

‘More oversight is needed’

The City of Vallejo has spent at least $54,000 on police drones and accessories since 2017, public records show. These include small drones that can fly inside buildings and thermal imaging cameras that can detect a person outside in total darkness.

Although the police department began purchasing drones in June, 2017, they did not log any flights until more than a year later, records show. By then, the policy requiring written permissions was already in place.

The department has five drones registered for active use with the Federal Aviation Administration, records show. The city declined to release police drone footage to Open Vallejo, arguing that they are investigative records exempt from disclosure, though the department posted footage from one drone-assisted arrest in July. The department’s flight logs, which record the date, time, flight duration and drone model used, show it has flown its drones for more than 30 hours since 2018.

In March, 2020, the department additionally purchased a $766,000 cell-site simulator, a device that tracks a person’s movements through their phone. Vallejo also uses surveillance technologies such as automated license plate readers and high-resolution security cameras.

Williams claims these technologies will help police solve and prevent serious crimes such as homicides and robberies, as well as quality-of-life issues such as sideshows and illegal fireworks activity. But some residents and privacy advocates say the department cannot be trusted with powerful surveillance technologies.

The department’s failure to show drone flight authorizations “should really leave no doubt that the current rules are not working and that more oversight is needed,” said Raquel Ortega, an organizer with the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California.

On Sept. 28, the Vallejo City Council voted to establish a Surveillance Advisory Board to provide input on surveillance issues.

Privacy activists began pushing for a committee last summer, after two Vallejo residents and the advocacy group Oakland Privacy filed a lawsuit alleging the city illegally acquired its cell-site simulator. (One of the plaintiffs, Dan Rubins, is a board member of Open Vallejo’s parent nonprofit Informed California Foundation, which had no role in the lawsuit.)

Following criticism from activists and the public over what they called last-minute changes that watered down the board’s powers, the council voted to revise the ordinance. On Nov. 16, it was amended to allow members of the public to sue the city if it does not follow the ordinance, and require the city to inform the board within 30 days after it uses new surveillance technologies.

“It’s not perfect, but it’s a lot better,” Kris Kelley, the co-chair of the Solano County chapter of the ACLU, said at the council meeting. Two Vallejo officers killed Kelley’s brother Mario Romero in 2012.

The city council appointed the board’s first seven members on March 8.

The drone policy should be “a prime referral” for the surveillance advisory board, Vallejo Mayor Robert McConnell said, adding that the department’s interest in eliminating the written authorization requirement could turn into a legal dispute. While the board can advise the city council on the policy, it should ultimately be the council’s responsibility to vote on amending the policy, McConnell said.

“It’s a situation crying out for resolution.” The Surveillance Advisory Board will hold its first meeting, online and in person at Vallejo City Hall, on Thursday, Apr. 21 at 6:00 p.m.