On July 31, 2023, a local homelessness advocate went to an encampment clearing on Sereno Drive and Sonoma Boulevard, allegedly stood in front of a tow truck to protest the sweep, was arrested, and had a heart attack in the back of a police car.

Police issued José Carrizales a citation for obstruction, which he signed from his hospital bed. Although prosecutors declined to file charges in the case, Carrizales still keeps the yellow slip of paper in his wallet. He says it was the only documentation of alleged wrongdoing he had received related to his activism — until now.

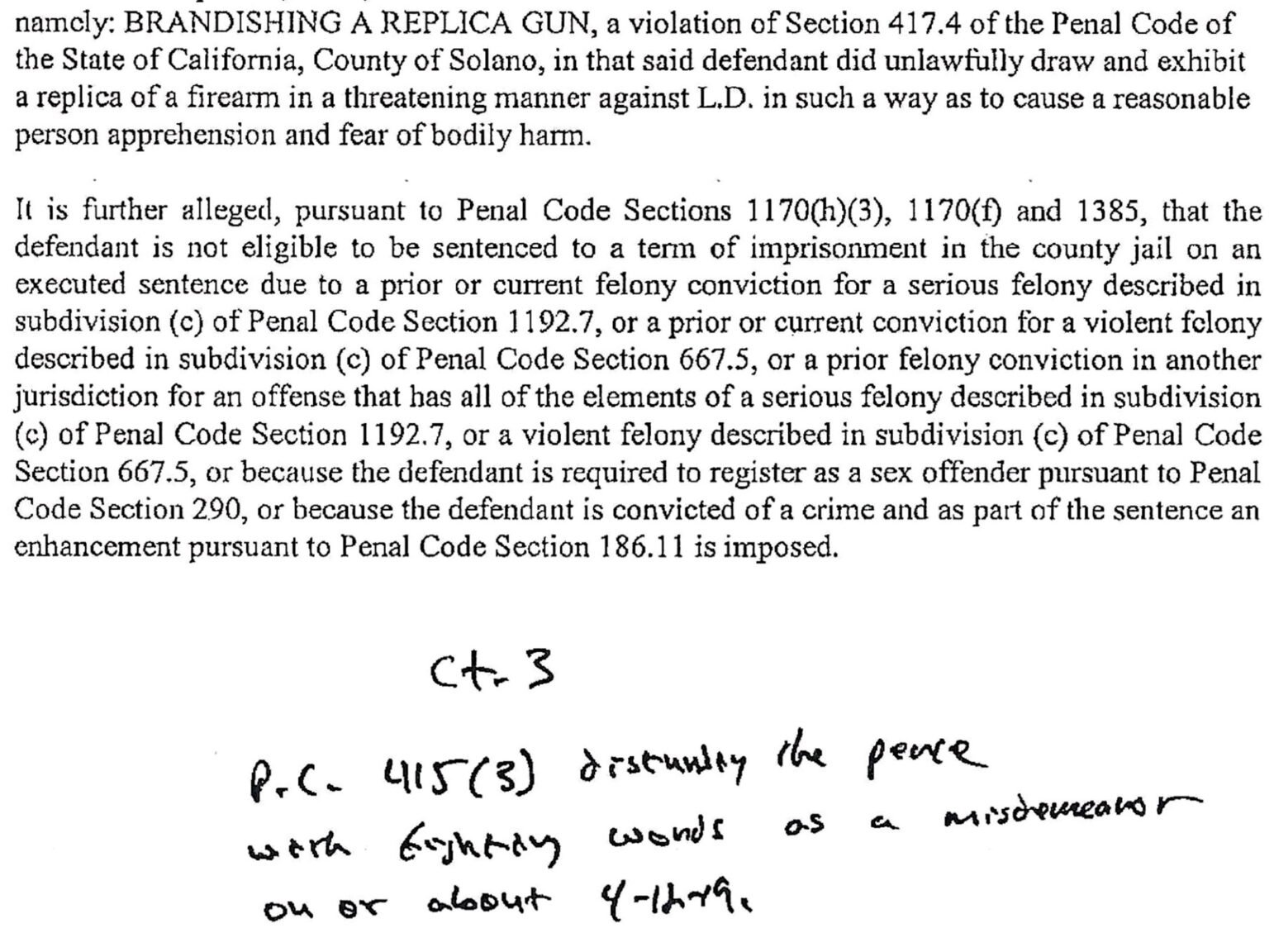

In October, Carrizales was notified that the Solano County District Attorney had filed a dozen charges against him spanning six separate incidents at homeless encampments throughout 2024. Of these, Carrizales is facing six charges for obstruction and six charges for “Disturbing the Peace by Offensive Language,” a seldom-used subsection of California’s disorderly conduct statute that First Amendment experts say raises significant free speech concerns.

Two of the alleged incidents appear to lack an underlying police report from an officer on scene. Only one report accuses Carrizales of using offensive words. And while the statute requires the use of language “inherently likely to provoke an immediate violent reaction,” body camera footage of incidents in which Carrizales was charged shows him criticizing police, asking for names and badge numbers, and chiding workers for participating in encampment cleanups and sweeps.

“I’m appalled, but on the other hand, bring it on,” said Carrizales’ criminal defense attorney Daniel Russo, who is representing Carrizales pro bono. “I’m old, but I like to fight.”

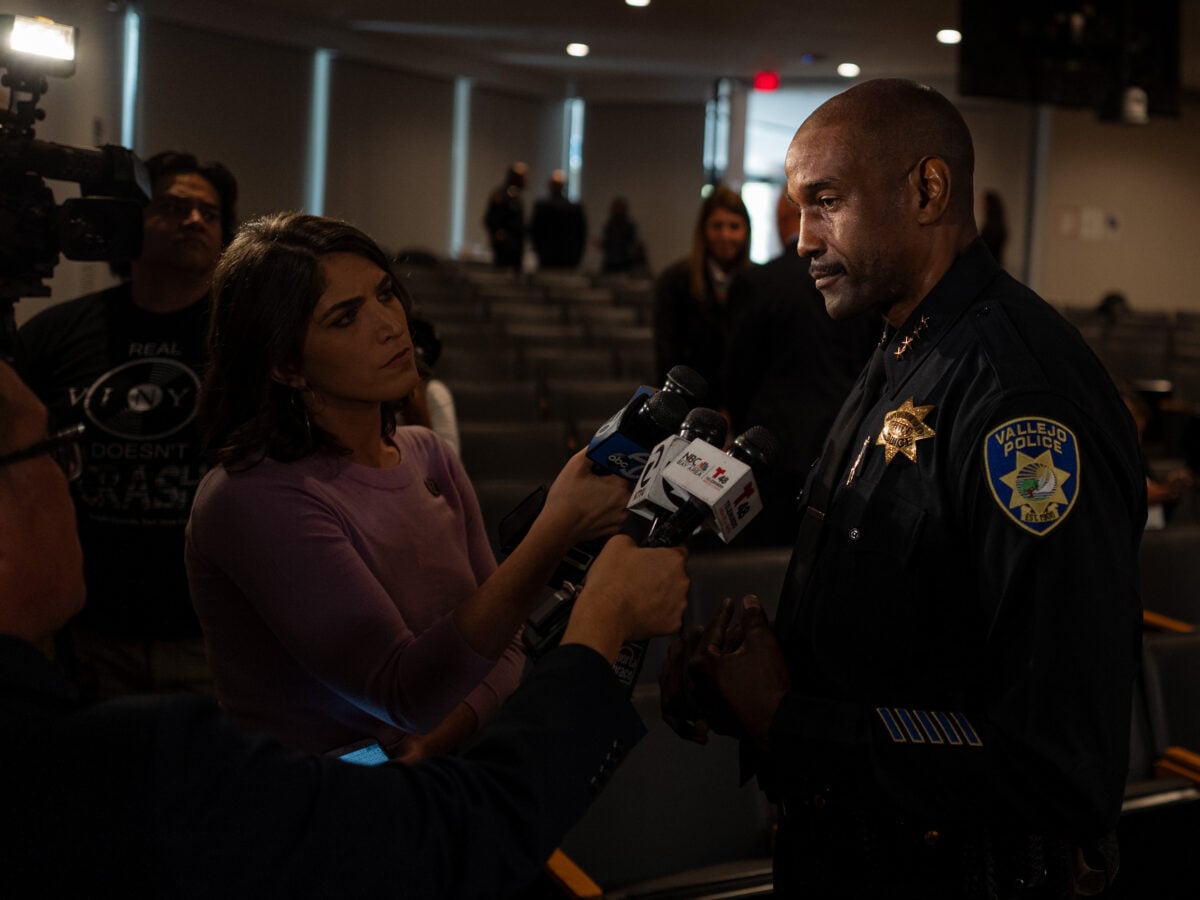

Open Vallejo reached out individually to each officer and deputy named in this story, all of whom either declined to comment or did not respond. Spokespeople for the Solano County District Attorney’s Office and the Solano County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to requests for comment. Vallejo police spokesperson Sgt. Rashad Hollis declined to comment.

‘You don’t want to put out his fire’

Carrizales, who often appears at encampments to assist homeless residents and protest sweeps, has been known to jeer staff, police and contractors facilitating the clearings. He does not deny that his temper can sometimes get the better of him. For Carrizales, the issue of homelessness is personal.

After his father died in 2013, Carrizales became homeless in Vallejo. For nearly three years he slept outside Vallejo’s John F. Kennedy Library. Like many other unhoused residents of the city, he would walk to the nearby waterfront to wash himself and find food through local resources. He says the experience propelled him to activism.

“That started my advocacy, and started my negative interactions with not only the local police, but the local government,” Carrizales told Open Vallejo.

In January 2016, an encounter with an old friend helped Carrizales get back on his feet. The man got him a job at a car dealership he managed in Sacramento. For much of 2016, Carrizales slept in his friend’s office while working at the dealership and showered at a local gym. He returned to Solano County that fall, and began volunteering at homeless encampments in 2022, both on his own and through a local homeless outreach organization. In 2023, the Vallejo City Council appointed Carrizales to the city’s housing commission.

According to the county’s most recent Point-in-Time Count, which occurs once every two years and is often seen as an undercount, more than 700 homeless individuals lived in Vallejo as of 2024.

City officials have recently signaled that two low-income housing developments, the Broadway Project and Homeless Navigation Center, are nearing completion after years-long delays and cost overruns reaching into the tens of millions of dollars. In the meantime, the city has faced a severe lack of shelter space to accommodate what has become the largest homeless population in Solano County.

In June of last year, the Supreme Court overturned a lower court ruling barring cities from criminalizing sleeping outdoors on public property without offering shelter. Vallejo ramped up clearings until the end of last year, when a Vallejo Public Works crew crushed a man to death with a backhoe during a cleanup on Christmas Eve. The new city council, whose members took office in January, temporarily paused such cleanups until the city could implement a “humane” approach to the city’s unsheltered community.

City councilmembers voted April 1 to continue sweeps later this month, while directing staff to identify locations for designated camping, according to the Vallejo Times-Herald. The move is a break from precedent, as previous councils have voted down similar camping proposals multiple times in the last five years.

As a housing commissioner, Carrizales was vehemently opposed to the council’s denial of designated camping areas. Emails obtained by Open Vallejo detail years of polemics to councilmembers, including one instance where he suggested he would move to former Vice Mayor Mina Loera-Diaz’s district to run against her.

While Carrizales’ approach has left some officials feeling aggrieved, even his toughest critics concede they value his advocacy.

“You don’t want to put out his fire,” Solano County Sheriff’s Office Homeless Outreach Coordinator Deputy Dale Matsuoka said to a homeless outreach team on March 7, 2024, according to body camera footage. “I’d rather have his fire than have him lose his steam.”

Fighting words

The U.S. Constitution provides broad protections for speech, and simply displaying or saying something offensive in public is not enough to convict someone of a crime, according to Eugene Volokh, a leading First Amendment scholar.

In 1968, California resident Paul Robert Cohen was arrested and convicted of disturbing the peace, after wearing a jacket in a courthouse that had the phrase, “Fuck the Draft” on the back. Three years later, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction in a landmark decision, famously affirming that, “one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric.”

In Carrizales’ case, a jury would have to determine whether his speech included “fighting words,” or personalized statements or insults inherently likely to provoke a violent reaction, Volokh told Open Vallejo.

In addition, “The charge is harder to make stick when it’s a police officer,” Volokh said. California jury instructions require jurors to take into account whether the words were said to a law enforcement officer, who are expected to show restraint.

“But you could imagine someone ranting enough at the police officer that even the local police officer, the worry is they might snap and start a fight,” Volokh said.

In 1942, the Supreme Court upheld the fighting words conviction of a man who called a police officer a “damned racketeer” and “a damned fascist.” However, Volokh said standards of decorum change over time, and that this would likely not be enough to reach a conviction today.

It remains unclear what offensive words prosecutors deemed criminal in all but one of the 2024 incidents in which Carrizales is charged, according to body camera footage and incident reports disclosed to Carrizales and obtained by Open Vallejo.

On Aug. 21, Vallejo police Lt. Jodi Brown and Ofc. Jaime Escalante arrested Carrizales during a sweep of an encampment at Lemon and Derr Streets. Carrizales approached the officers and asked them for their names and badge numbers, body camera video shows. Brown stopped Carrizales from passing three police cars being used to block off the scene, telling him repeatedly to not cross the barricade, before physically pushing him back and warning that he would go to jail. Brown then placed Carrizales under arrest for obstruction as he backed away from the officers.

At no point does the body camera footage depict Carrizales using threatening or offensive language toward officers, and none of the three officers involved in the arrest mentioned any use of offensive language in their reports. Assistant to the City Manager Natalie Peterson wrote in an email to Brown later that day that Carrizales had yelled at her from the back of a police car, asking if she was proud of herself, but did not mention any offensive language.

Carrizales later alleged that the Solano County Sheriff’s Office retaliated against him after Matsouka towed his car, which was parked half a mile away, while he was in custody. Brown wrote in her police report that the Solano County Sheriff’s Office towed the car because it was in a “high crime area” and because she believed he was living out of it at the time. Carrizales told Open Vallejo he was not living in his car, but also believes that if he was, it should not have made a difference.

The incident marked Carrizales’ only arrest in 2024. On other occasions, officers filed police reports but did not arrest Carrizales or give him a citation onsite — including during a controversial incident last July that led to his resignation from the Vallejo Housing Commission.

During a debris cleanup on Mare Island Way on July 10, Carrizales confronted Matsuoka, calling him a “Three Percenter.” The comment referenced a 2021 Open Vallejo investigation that identified Matsuoka as one of several sheriff’s deputies who shared social media posts promoting the Three Percenters, a far-right extremist movement whose adherents played a key role in the Jan. 6, 2021 assault on the U.S. Capitol.

In body camera footage of a separate incident obtained by Open Vallejo, Matsuoka describes the Three Percenters as a “white supremacist organization” to a nearby contractor, although the movement was not explicitly founded as such; local chapters and the organization’s former national leadership have attempted to distance themselves from the allegation.

“He thinks I’m racist,” Matsuoka continues, referring to Carrizales. “That’s fine. It’s America, man, people are allowed to think how they want to think.”

After Matsuoka instructed Carrizales to stay clear of the construction zone during the July 10 incident, the activist began yelling at a public works employee, calling him a homophobic slur in Spanish.

“Carrizales feigns advocacy for the unhoused in order to come clean up areas and promote resistance to the government and encourage breaking laws,” Matsuoka later wrote in a police report documenting the incident.

City Councilmember Peter Bregenzer, who viewed body camera footage of the incident, gave Carrizales the choice of resigning from the housing commission or facing a hearing over his actions, according to the Vallejo Times-Herald. The activist chose the former and later apologized in a letter to the editor published in the Times-Herald.

Vallejo city council members are not routinely briefed on individual law enforcement investigations, and Bregenzer has not publicly disclosed how he came to view the video. He did not respond to a request for comment.

Of the six incidents in which Carrizales is charged, the July 10 encounter is the most specific and well-documented case as it pertains to California’s offensive language statute. Volokh, who reviewed the body camera footage, said Carrizales’ conduct likely did not meet the legal threshold.

“I think that’s the kind of thing that probably wouldn’t qualify,” Volokh said. “If it’s a total stranger, that might make it worse, but on the other hand, you might say in context, he’s just trying to get a rise out of me, that this isn’t really an insult.”

In other incidents, there is even less documentation that a crime had been committed.

At an Aug. 7 encampment cleanup off Sereno Drive and Sonoma Boulevard, Carrizales allegedly did not move away from the scene when asked, but later removed himself without incident, according to law enforcement records. He was ultimately charged with obstruction and using offensive language.

But the only documentation of the Aug. 7 interaction was an overview of 2024 incidents involving Carrizales written by Vallejo Police Det. Stephanie McDonough. The report notes that “All incidents and interactions” were captured on body camera, but no footage from that day appears to have been produced to Carrizales by prosecutors. Nor does it appear that McDonough was present at the sweep.

McDonough’s summary makes no reference to offensive words in relation to the Aug. 7 incident, records show.

Similarly, prosecutors provided no contemporaneous police report or body camera footage of an alleged incident on July 28. McDonough’s summary does not allege that Carrizales obstructed law enforcement or used offensive words — only that he “arrived on scene and started to demand the names and badge numbers” of officers. For this incident too, Carrizales was charged with obstruction and using offensive words.

In a May 20 incident also cited in his criminal complaint, Carrizales was not the subject of the police report turned over by prosecutors. Matsuoka’s body camera footage shows that another man yelled at officers for what he called an illegal sweep off Lewis Brown Drive in north Vallejo. In a police report, Matsuoka alleged that the man’s actions left workers on scene “uncomfortable and feeling threatened,” in likely violation of the offensive words and unreasonable noise provisions of California’s disturbing the peace statute.

Matsuoka also wrote in his report that Carrizales had encouraged the man’s behavior. However, the document does not mention Carrizales himself using offensive language and only names him as an “investigative lead.” Although Carrizales was charged in this incident, the other man was not, court records show.

Charged language

Open Vallejo analyzed 10 years of criminal charging data from all nine Bay Area counties to determine which district attorney offices have prosecuted individuals under the state’s offensive words statute. Some counties, like San Francisco and San Mateo, use the charge sparingly or not at all. When the charge was used, it typically appeared as a bargaining chip, public records show.

Solano County prosecutors have charged defendants with at least one count of using offensive words 34 times in the last decade, public records show. It appears that no charge of offensive words has ever made it to a jury trial during that timeframe. The charge was dismissed in 11 of these cases.

Public records reviewed by Open Vallejo show several cases in which felony charges were pleaded down to a single charge of offensive words in a public place.

In one such case, a man was charged with three counts of felony sexual assault on a minor, which allegedly occurred in a Burger King restaurant in Vacaville in 2017. The man, who was 25 at the time, was an assistant manager. The alleged victim was 17.

The case was set to go to trial in August 2022, but five days before the trial date, the attorneys struck a deal.

On Aug. 25, 2022, a fourth count of offensive words in a public place was penciled in at the bottom of the complaint, and Judge Jeffrey Kauffman dismissed the three felony sexual assault charges in a hearing later that day. The defendant’s plea deal included 29 days in jail, one year of probation and a no-contact order to stay away from the victim. He was not required to register as a sex offender.

Other cases reviewed by Open Vallejo include charges of child molestation, child cruelty, domestic violence and felony threats to terrorize — all pled down to offensive words.

“It is very common nationwide for state prosecutors to use ‘disturbing the peace’ type charges as lesser included offenses as a target in plea bargaining,” said Ken White, founding partner of Brown White & Osborn LLP and a former federal prosecutor. “They’re rarely challenged although they are of dubious First Amendment validity as used.”

On March 12, Carizales filed a motion to dismiss the charges against him, arguing that they violate the First Amendment. The prosecution filed its opposition on April 8. A hearing on the motion is scheduled for April 14.

For Russo, Carrizales’ defense attorney, the relative rarity of offensive words prosecutions raises suspicions about the charges against his client, he told Open Vallejo.

“What logical conclusion do you draw from that? What the logical conclusion is, they want him to shut the fuck up and stay the fuck away from the homeless,” Russo told Open Vallejo. “You don’t have to be a fucking paranoid to think that people are after you when they are.”