The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday ruled in favor of a former Indiana mayor convicted of accepting an illegal gratuity from a local business, narrowing the interpretation of a federal law meant to curb government corruption.

The decision was issued by a 6-3 majority of the court. In his majority opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote that the federal statute in question — Title 18, section 666 of U.S. Code — prohibits bribes to state and local officials but “does not make it a crime for those officials to accept gratuities for their past acts.”

The ruling stemmed from a case involving James Snyder, the former mayor of Portage, a city of roughly 38,000 people near Lake Michigan. While Snyder was mayor in 2013, the city awarded two contracts to Great Lakes Peterbilt, purchasing five garbage trucks from the company for more than $1.1 million, according to court records. The next year, Snyder accepted a $13,000 check from the garbage truck company.

The mayor claimed that he earned the money by providing consulting services to Great Lakes Peterbilt. But employees testified during Snyder’s trial that he had never performed consulting work for the dealership, and federal investigators found no evidence of such work.

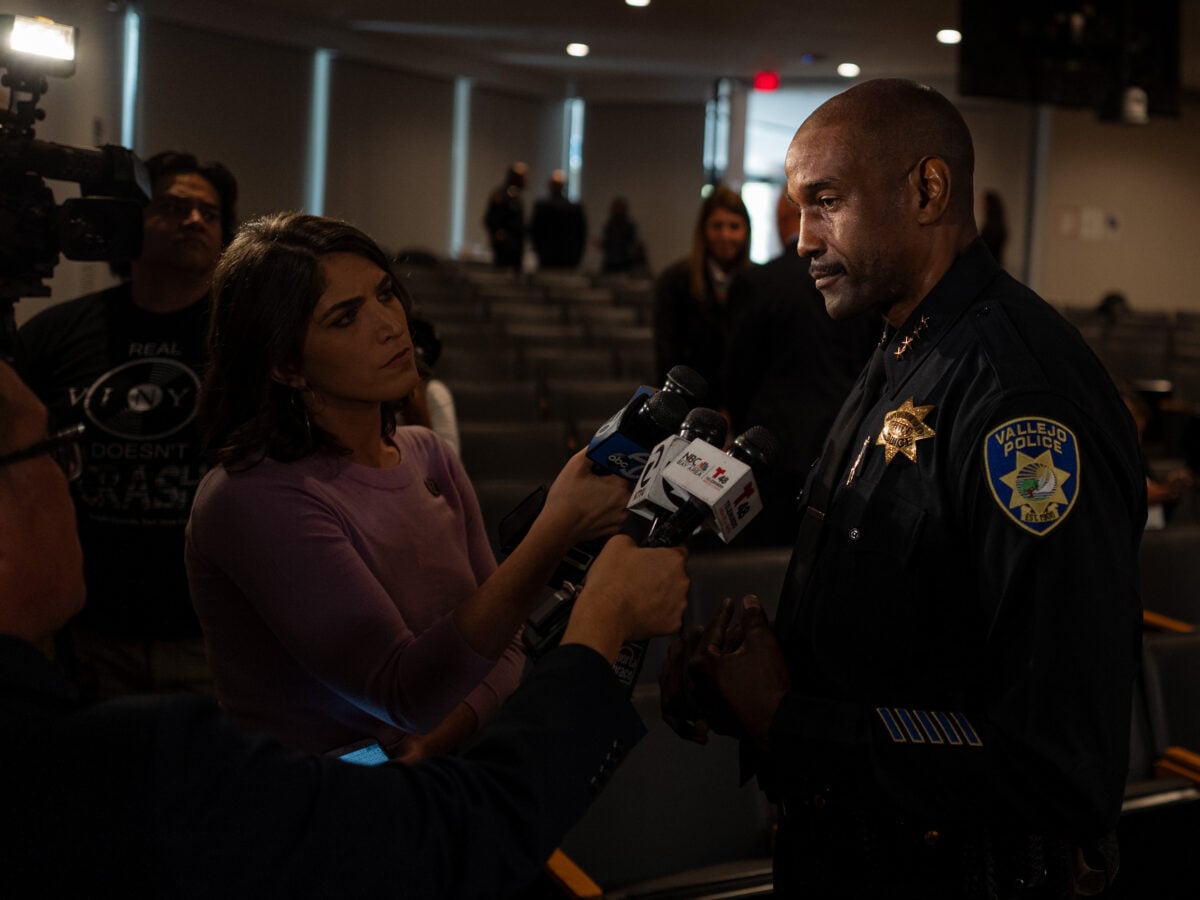

In 2017, Federal prosecutors used the same statute to charge a Vallejo official, Donald Burton, for his part in an unrelated bribery scheme. Investigators found that Burton abused his role as Vallejo’s landscape manager by soliciting a bribe from the owner of a landscaping company in exchange for steering city contracts to the company. Later that year, Judge John A. Mendez sentenced Burton to a year in prison and a $10,000 fine, court records show.

Kavanaugh distinguished between bribes and gratuities in Wednesday’s ruling. Bribes are typically given or agreed upon before an official act in order to influence the outcome, Kavanaugh wrote. Meanwhile, gratuities are payments provided after an official act as a thanks or reward.

“While American law generally treats bribes as inherently corrupt and unlawful, the law’s treatment of gratuities is more nuanced,” Kavanaugh wrote. “Some gratuities might be innocuous, and others may raise ethical and appearance concerns.”

Kavanaugh also noted that state and local governments often regulate what gifts local officials may accept. Federal prosecutors’ broader interpretation of the statute would “create traps” for state and local officials, including teachers and postal workers, Kavanaugh wrote. It would leave them guessing about what gifts they can accept, he said, “with the threat of up to 10 years in federal prison if they happen to guess wrong.”

The case came down along ideological lines, with conservative Justices John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett joining the court’s majority opinion. Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan dissented.

The ruling follows reporting by ProPublica last year that uncovered Thomas’ and Alito’s acceptance of undisclosed luxury travel and other gifts. Late last year, the court released its first-ever code of conduct.

In her dissenting opinion, Jackson disagreed with Kavanaugh’s narrower interpretation of the statute, asserting that gratuities are “plainly covered” in the text of the law. Jackson wrote that she agrees that the statute should not subject government employees to prosecution “when grateful members of the community show their thanks.” But, she added, “nothing about the facts of this case implicates any of that kind of conduct” and the statute is equipped with “meaningful guardrails.”

“The real cases in which the Government has invoked this law involve exactly the type of palm greasing that the statute plainly covers,” she said. “After today, however, the ability of the Federal Government to prosecute such obviously wrongful conduct is left in doubt.”