Editor’s note: In this column written especially for Open Vallejo, author Brendan Riley recounts the story of Frank Melville, Vallejo’s ‘boy bandit’ who was granted a second chance at life. In telling this part of Vallejo’s history, we are mindful that many in this community have been denied a similar opportunity to continue writing their own stories. That is part of why we believe Melville’s story is meaningful: it tells a story of what might have been.

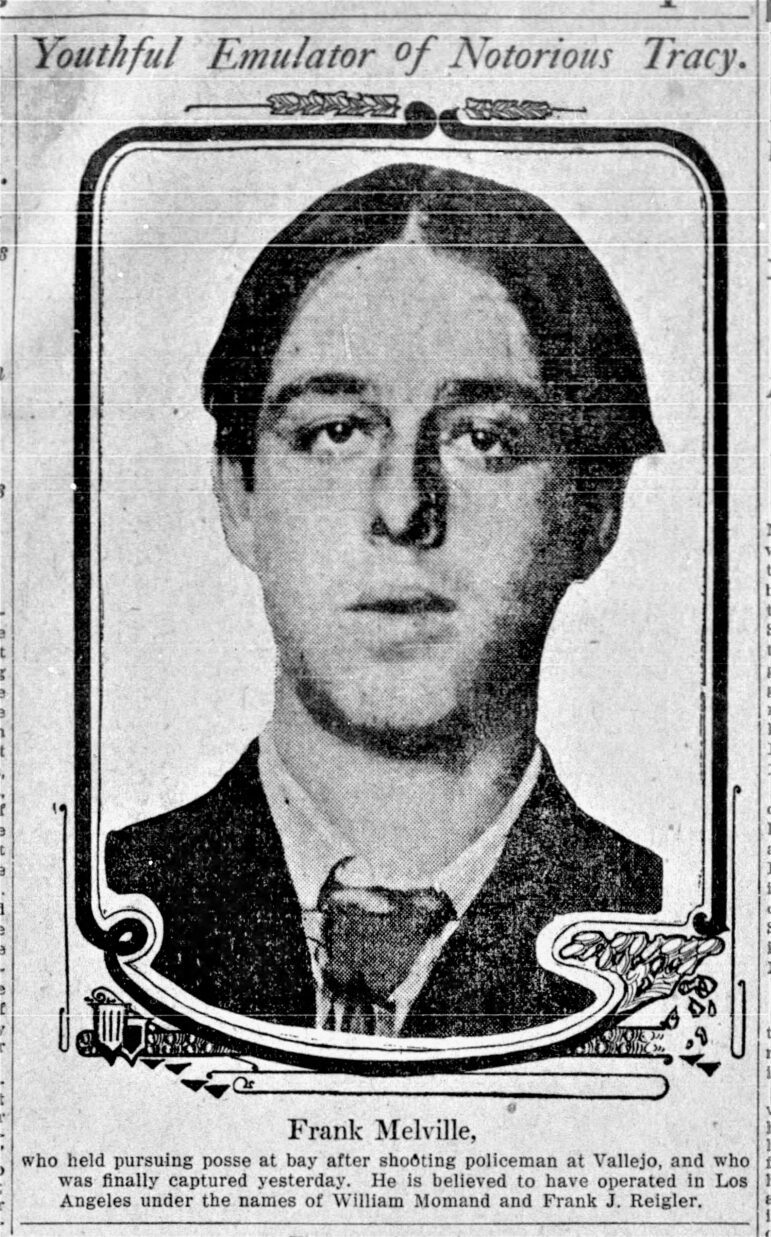

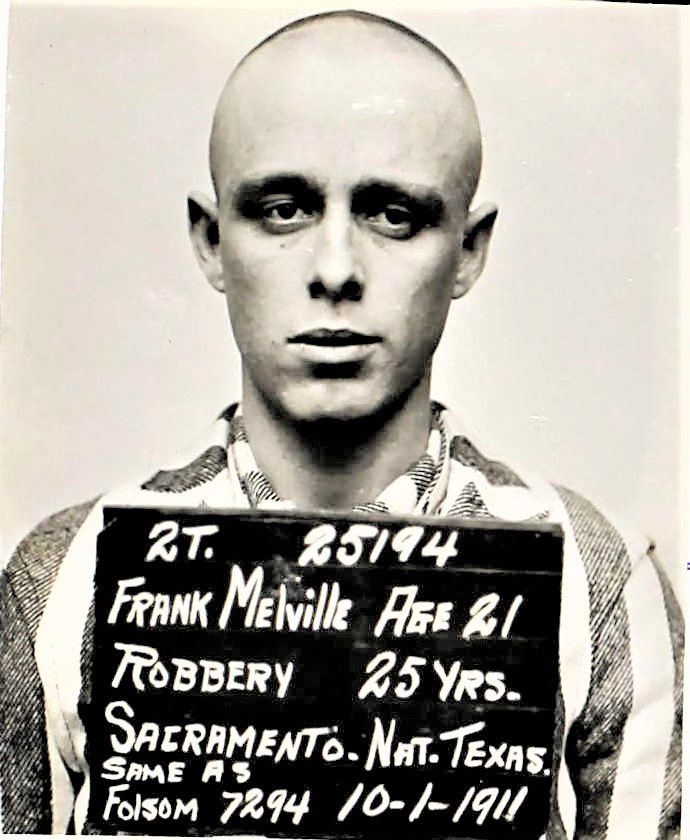

Vallejo has had its share of tough characters over the years, including Frank Melville, the infamous “boy bandit” whose stint as a gun-toting robber and thief in the early 1900s in California drew comparisons to outlaw Jesse James.

Melville’s criminal career, which began in his teens, included a string of saloon holdups and shootouts with police that led to a lengthy prison sentence. But he escaped, evading the authorities for nearly 20 years.

Melville led an exemplary life during that long stretch on the run, which enabled him to avoid a return to prison when he was finally caught. Instead he won high praise — and a full pardon.

Born Francis Hogan and orphaned as a boy, public records show, Melville was later adopted by a Vallejo farmer. According to local police, he left the farm and was arrested in late 1906, at age 17, for a robbery in Marysville. That’s when he began using the name Melville; his other aliases included William Momand and Frank Reigler. The robbery led to time in a state reformatory in Ione, near Sacramento.

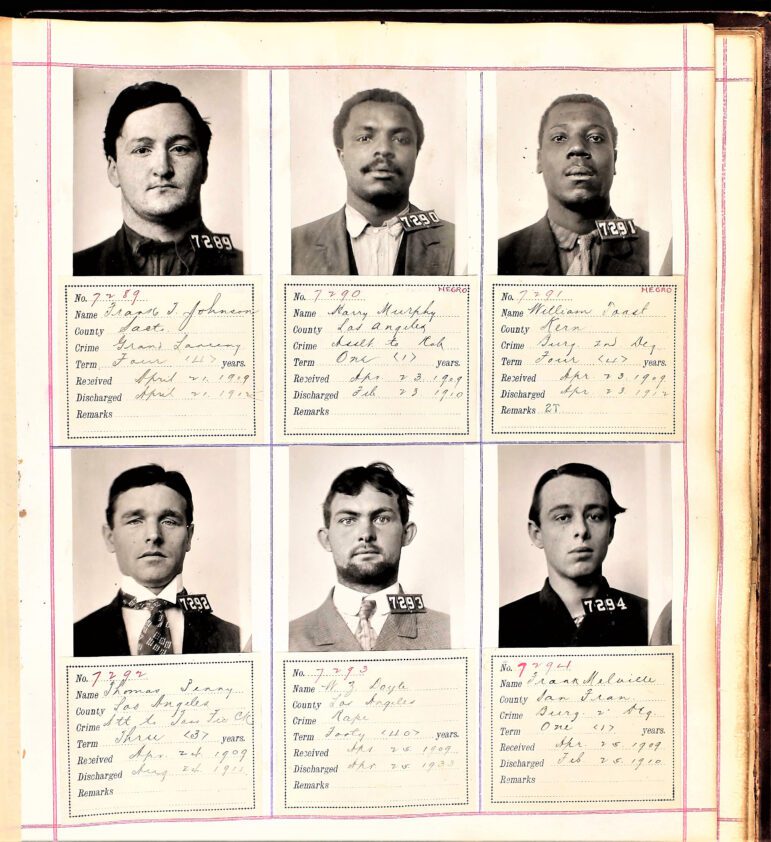

Melville was convicted of another robbery, in San Francisco in early 1909, and was sentenced to a year in Folsom State Prison. He then worked in various California towns for nearly a year before embarking on a long string of robberies starting in early 1911. The robberies continued until a running gun battle with police in the Vallejo area on June 15 and his arrest in nearby Benicia the next day.

More than 150 men armed with shotguns and rifles pursued Melville, who was wounded in the left arm and right leg, according to the Vallejo Evening Chronicle. Cornered at Glen Cove, between Vallejo and Benicia, Melville managed to slip past posse members and hide amid tules in shallow water on the Carquinez Strait. He said in an interview with the Evening Chronicle that when pursuers got too close, he would hold his breath underwater until he was sure they had moved on. He managed to get to a Benicia rooming house where the suspicious proprietor alerted officers who arrested Melville.

Accounts of the crime spree ran in newspapers across the country.

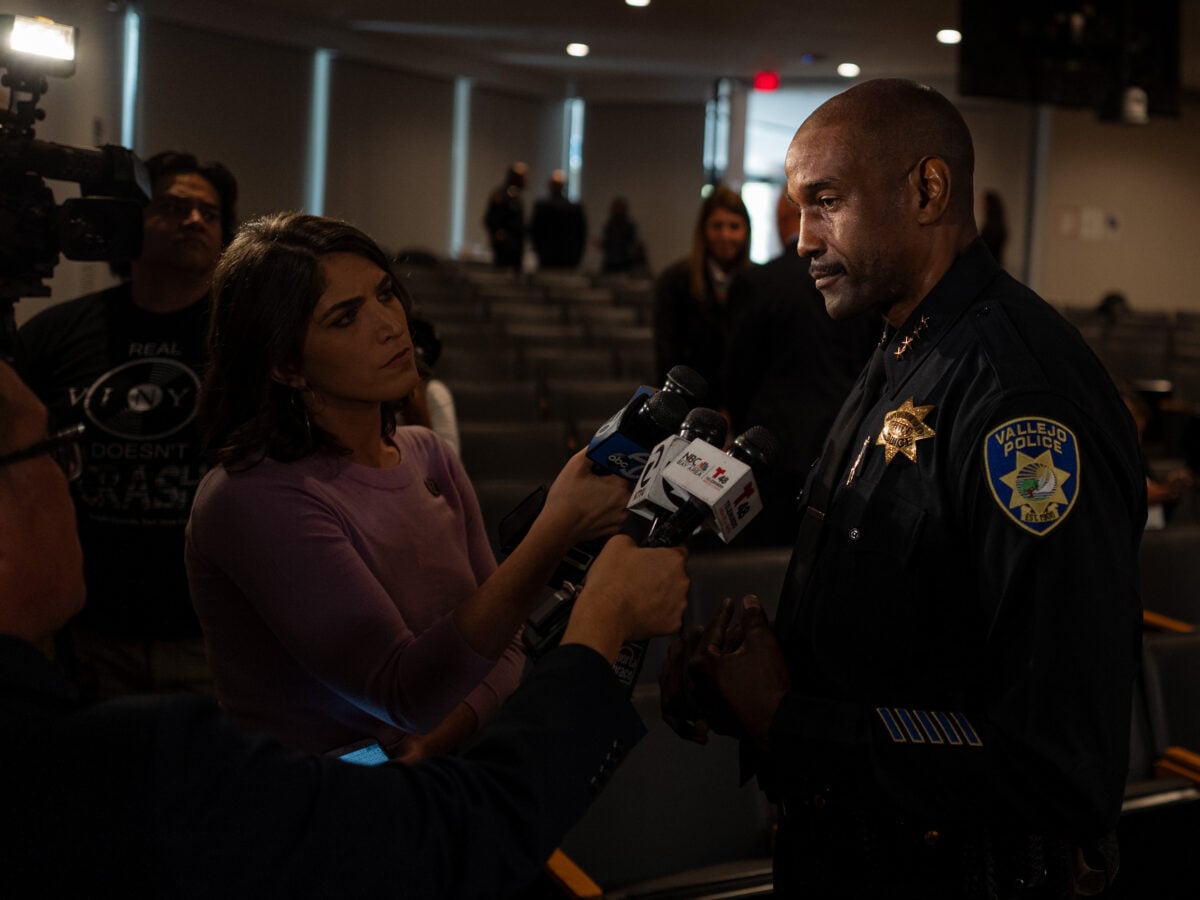

Brendan Riley / Special to Open Vallejo

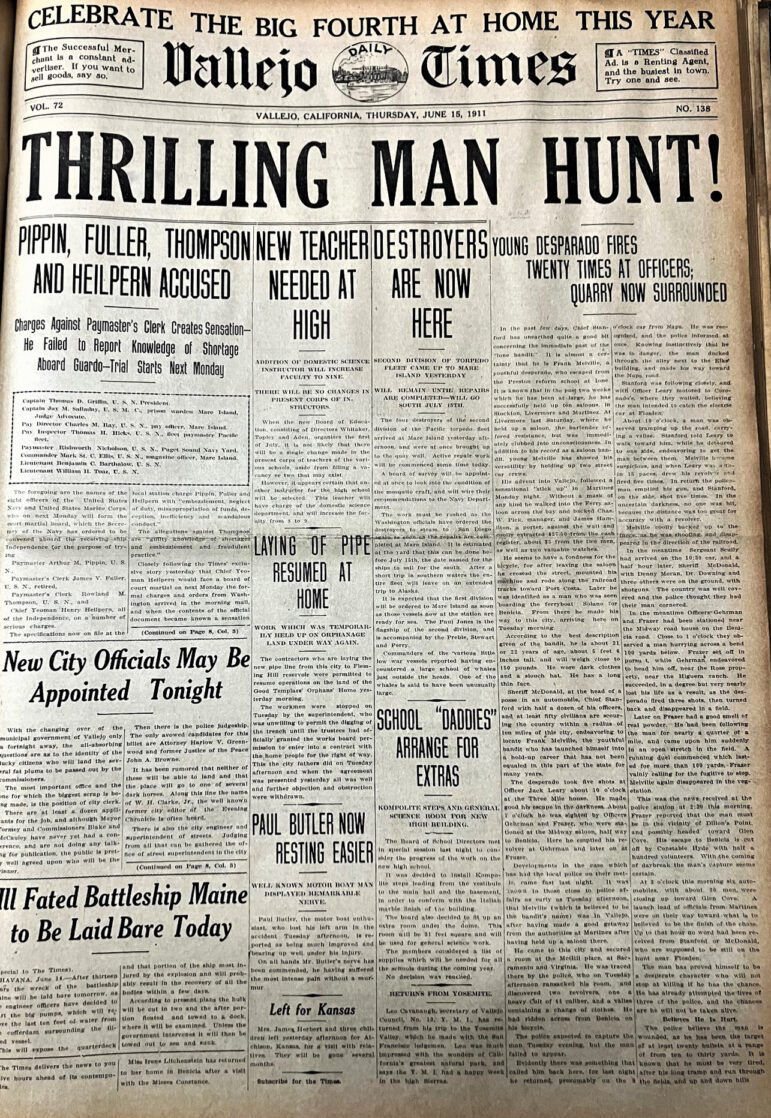

The front page of the June 15, 1911 Vallejo Times. Credit: Brendan Riley / Special to Open VallejoAlthough the boy bandit fired numerous rounds, there were no reports of any of his pursuers being wounded. “While he would undoubtedly shoot to kill, he is a notoriously bad marksman with a revolver,” the Oakland Tribune noted. Following his arrest, Melville appeared “stripped of the glamor that surrounds him because of his display of desperate courage,” the Evening Chronicle observed. “He has a hang-dog air that goes ill with his reputation as a desperado.”

Under questioning following his arrest, Melville admitted to more than a dozen hold-ups, mainly in saloons, in Bakersfield, Kern City, Fresno, Stockton, Lodi, Sacramento, Martinez, Livermore and Vallejo. He robbed some of the saloons twice and often fled from the scene on a bicycle, which he once rode for seven hours from Sacramento to Stockton, only to come up empty-handed when a bartender fired a gun at him, according to an article in the Medford Mail Tribune.

Melville’s statement to authorities, according to the Vallejo Evening Chronicle, “was more in the nature of a boast than an admission of a man driven to confession by a desire to unburden himself of a sinful burden.”

Prosecutors in several counties wanted Melville tried on their turf, but agreed to have the case handled in Sacramento where the district attorney said he was sure to get a conviction, according to the Evening Chronicle. The Sacramento Bee reported that Melville had a severe stutter and when the prosecutor asked him in pretrial proceedings to repeat certain sentences, “his efforts sounded so much like the voice of the holdup that several witnesses immediately pronounced it one and the same.”

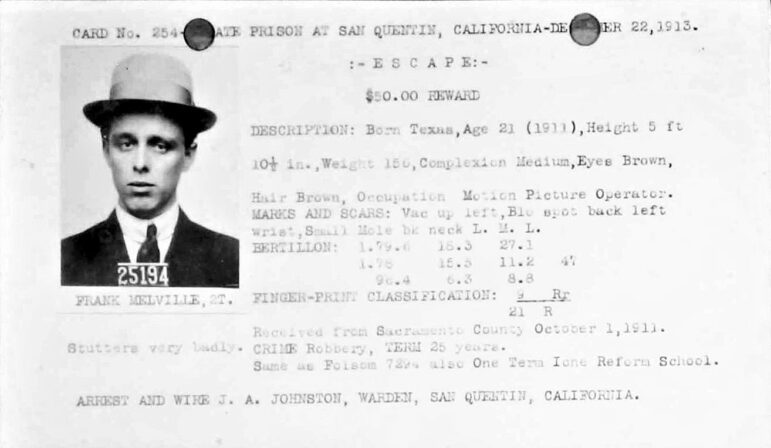

On Sept. 29, 1911, Melville, age 22, pleaded guilty to holding up a saloon in Sacramento and was sentenced to 25 years in San Quentin. He had considered going to trial but decided against that after prosecutors agreed to not pursue other charges that could have resulted in a life sentence. The Sacramento Bee reported that he also asked to be sent to San Quentin rather than Folsom because “a convict named Dutch Baker, an arch enemy, is confined in Folsom and murder would follow if both were kept in the same prison.”

Melville may have requested San Quentin, but he had no intention of staying there. On Dec. 23, 1913, he and another convict, James Hurley, escaped by climbing through a skylight to a cellhouse roof and using a rope, taken from a workroom, to slide 80 feet down a wall to freedom. Described as “desperate” in multiple news accounts, the two men had a head start of about an hour before guards noticed they were missing.

San Quentin Warden James Johnston, advised that the escapees might have stolen two handguns and a rifle from a home a few miles from the prison, issued a “shoot to kill” order to nearly 100 armed searchers combing the low hills around the prison. But Melville and Hurley avoided detection and managed to get across San Francisco Bay to the Oakland-Berkeley area.

A week after the escape, Hurley was captured in San Jose, about 60 miles from San Quentin, as he jumped off a slow-moving freight train. But Melville remained at large. His last know location in the San Francisco Bay area was in Berkeley, where he pulled a gun on a man and forced him to take off his coat and pants. He fled with the clothing, leaving behind a prison-issue rain slicker that he had been wearing.

After about two years, Melville wound up in New York, now going by the name William Harry Collins — Harry for short. He stayed out of trouble and was able to get a job as a delivery driver with the American Express Co. He soon met and married Della Scanlon, to whom he said nothing about his crimes, and began raising a family.

But 17 years after his prison escape, Collins’ past finally caught up with him. He got into a fistfight in April 1931 that resulted in an arrest for assault. The charge was dropped but his fingerprints were routinely sent to the federal Identification Bureau in Washington, D.C., where authorities matched them to his California prison prints.

In the meantime, Collins had moved to another home in New York City, leaving no forwarding address. Police finally caught up with him in mid-June 1932. According to one newspaper account, Collins had just parked his truck to make a delivery at the Chrysler Building in Manhattan when two detectives approached and one said, “Hello there, Frank Melville.” He didn’t resist when arrested and made no attempt to deny his identity.

Newspaper accounts of Collins’ arrest played up his record as a devoted husband, father of two daughters and trustworthy American Express employee for 16 years, and prominent New York attorney David Garrison Berger volunteered to represent him at no charge.

Collins’ soon filed a motion to block his extradition to California and a request for a pardon. He included letters of support from his wife, his employer, Joseph Wilson of the New York Federation of Labor, Thomas J. Lyon of the Railway and Express Employees Association and, notably, New York Police Commissioner Edward Mulrooney.

In Sacramento, where Collins, as Frank Melville, had been sentenced to San Quentin Prison 21 years earlier, District Attorney Neil McAllister announced that he would not seek Collins’ return to authorities there. Within a week of the arrest, California Gov. James Rolph declared he wouldn’t try to extradite the fugitive.

“I think the man’s record should be blotted out,” the governor said. “He seems to have made good. Far from following him to the ends of the earth, the state and society should slap him on the back. He should be commended for making good. The purpose of punishment is not to wreak vengeance.”

“A prison is supposed to rehabilitate men and where a man has been rehabilitated through his own efforts I cannot see where the prison can further the work,” the governor added.

Collins, elated with the break promised by Rolph, told the New York Times, “Now I can go back to my wife and children and work for them without fear of being arrested at any time and sent back to prison for what would be virtually a life term.”

Although Rolph was ready to immediately grant Collins’ petition, there was a delay of nearly four months. Because he had been twice convicted of a felony, Collins had to first apply to the California Supreme Court. On Oct. 11, 1932, with the high court’s recommendation finally in hand, Gov. Rolph issued an unconditional pardon.

Collins returned to his American Express job and lived with his family in New York. When he died more than 40 years later, at age 83, there was no newspaper rehashing of the story of the one-time “boy bandit.” Harry Collins, also known in his early years as Frank Hogan, Frank Melville, Frank Reigler and William Momand, was buried in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York City.

Author’s note: I had run across stories of the “boy bandit” being sent to San Quentin Prison but hadn’t found the accounts of his escape and reformed life afterward. Rebecca Kyles of Vallejo did find those later stories in her research and shared them with me.