Vallejo City Manager Greg Nyhoff held a series of previously undisclosed meetings last year with executives from the Nimitz Group and the Southern Land Company, the property owner and the master developer of the Mare Island shipyard megaproject.

Nyhoff did not tell the City Council or the city’s Mare Island negotiating team about the meetings until months later. Following the meetings, Nyhoff pushed for terms of the redevelopment deal to be altered to the detriment of the city, an Open Vallejo investigation has found.

After two top city employees involved with the Mare Island project raised concerns about Nyhoff’s conduct, including his side-channel meetings with the developers, they were fired.

The sprawling former Navy shipyard on Mare Island, once the city’s main economic engine, is now Vallejo’s biggest-ever real estate opportunity. With space for more than ten thousand homes, millions of square feet of job-producing businesses and retail space as well as parks, a fully redeveloped Mare Island has the potential to reverse the once-bankrupt city’s fortunes.

However, relatively little has happened there since the military left in 1996, a century and a half after the shipyard’s founding. For years, with Miami-based real-estate giant Lennar Corp. apparently content to sit on vast swaths of vacant land while slowly building small numbers of homes, a fallow Mare Island has been a visible symbol of Vallejo’s unrealized potential.

That all seemed poised to change last year when the Nimitz Group, a consortium of local winemakers and Gaylon Lawrence Jr., a Tennessee billionaire, secured control of a total of more than 800 acres on the island as well as exclusive negotiating rights with the city to develop.

Unlike Lennar, Nimitz had local ownership. Partner Dave Phinney, a winemaker and distiller, makes his Savage & Cooke whiskey on Mare Island. And unlike Lennar, Nimitz appeared willing to build quickly, and on the city’s terms.

In a negotiated term sheet unanimously approved by the City Council in October 2019, Nimitz agreed to take over significant costs related to island upkeep as well as fulfill specific performance benchmarks, with at least 100,000 square feet of construction to be finished every three years.

But before that October City Council meeting, Nyhoff ordered the term sheet edited — at Nimitz’s request, and over protests from his own negotiating team.

Southern Land Company, a major mixed-use developer based near Nashville, officially joined the project this February, a few weeks before the term sheet was supposed to have been finalized and become binding.

The term sheet included provisions that would have potentially saved Vallejo taxpayers millions of dollars, while also guaranteeing significant progress on Mare Island.

Last year’s agreement is now being “renegotiated,” a spokesperson for Nimitz Group said, with no clear indication of when a new deal might appear.

In an interview, Nyhoff told Open Vallejo the developer meetings were routine contacts. Changes to the term sheet were simply part of ongoing negotiations, he said.

But Nyhoff’s actions so harmed the city’s position that members of the negotiating team began to question his motives, as well as the integrity of the Mare Island negotiations, they told Open Vallejo.

“Greg’s intent was to shred” the term sheet after meeting with Southern Land Company, said Will Morat, who was the city’s lead negotiator on the deal. He was fired on April 23, approximately two months after being put on administrative leave.

Nyhoff “wanted me to water down the agreement, in the interest of” the developers, he added. “I said, ‘Greg, I can’t do that.’ He said, ‘If you don’t, I’ll find someone who will.’ I knew at that time something was up, and I knew my job was in jeopardy, and if I didn’t act in the interest of a developer, my job as a public employee was in danger.”

“I would say it’s a fact that after he went to Tennessee and met with Southern Land in October, that’s when everything changed,” Morat added.

Carolyn Drake / Magnum Photos

A building on Mare Island once used by the U.S. Navy. Credit: Carolyn Drake / Magnum PhotosNyhoff said he met with Southern Land Company officials on “three or four” occasions in the fall and early winter of 2019, including during an official, city-paid October 2019 junket to Tennessee for a city manager’s conference in Nashville, where both Southern Land Company and Nimitz Group principal Gaylon Lawrence, Jr. have offices.

At Nimitz’s behest, Nyhoff said he inserted into the construction milestones a single, ambiguous term — “substantially” — despite objections from Morat and special advisor Slater Matzke, who was also fired on April 23.

“Developers will call me, owners will call me, and say, ‘Hey we’re good with this, except for this word,” said Nyhoff, who noted the change had approval from the city attorney. “This is a normal part of negotiations that go on.”

Citing possible future litigation and the confidentiality of personnel matters, he declined to address why Matzke and Morat, along with former city spokesperson Joanna Altman, who’d been employed with Vallejo for more than seven years, were all let go on the same day.

But in an interview with this news outlet on Nov. 19, all three said they believe they were fired at least in part because they expressed concerns about Nyhoff to an investigator hired by the City Council to look into complaints about the city manager’s conduct, describing what they said was Nyhoff’s suspicious behavior around the Mare Island deal.

In the interview as well as in claims filed with the city, the three allege that Nyhoff bullied subordinates, used racially inflammatory language, and negotiated against the city’s interests on Mare Island — which Morat characterized in his claim as “graft in the form of the City Manager’s unethical, corrupt and illegal conduct with respect to city contracts.” They were fired in retaliation, the claims allege.

In an email to a San Francisco Chronicle columnist last summer, Randy Risner, then the acting city attorney, said the corruption claims were “investigated,” and “found not credible.”

‘I’ve never seen anything like it’

Prior to the meeting with Southern Land and Lawrence in Tennessee, Nyhoff had taken a high-level, hands-off approach to Mare Island, letting Morat, Matzke, and the rest of the city’s negotiating team take the lead, the former employees said.

After that trip, however, “Nyhoff was interjecting himself into active negotiations, in a way that was weakening the position of the city, to the benefit of the Nimitz Group, and now Southern Land,” Matzke said.

“It was an extraordinary cause for concern, and it was something we talked about amongst ourselves after we learned of it,” he added. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

An expert in government ethics stressed that Nyhoff’s conduct did not appear to violate any laws.

“He could be disciplined or fired for doing something that’s not in the city’s interest, but it doesn’t sound like anything illegal,” said Robert Stern, the founder and president of the Center for Governmental Studies and co-author of the California Political Reform Act. “If the City Council doesn’t like what he’s doing, they can do something about it.”

Next month, Nyhoff will enter the fourth of a five-year contract with Vallejo.

In that time, the city has received national attention for a series of police shootings and a practice, revealed by Open Vallejo, in which certain police officers bend points of their badges after killing civilians. This has fueled widespread public outcry, including a petition on Change.org with more than 3,000 signatures calling for Nyhoff to be fired.

The investigator who interviewed Altman, Matzke, and Morat before they were fired was working at the direction of the council.

The City Council held a special closed session meeting in April, in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, to discuss Nyhoff’s performance.

Instead of censuring Nyhoff, the council praised him. In a letter issued in late April, the City Council said it was “united in support” of “our city manager and his leadership.”

Reached for comment Monday, Councilmember Robert McConnell, the city’s mayor-elect, said that Nyhoff should have disclosed his developer meetings, but “it doesn’t really concern me that much, because the final determination” on any land deals “is up to the council, anyway.”

“Whether there was impropriety in the eyes of some, I think some are preordained to see it that way, because Mr. Nyhoff has not been as open as he needs to have been with the City Council,” McConnell said. “That’s one of the things I’ve been talking with him about.”

Favorable terms

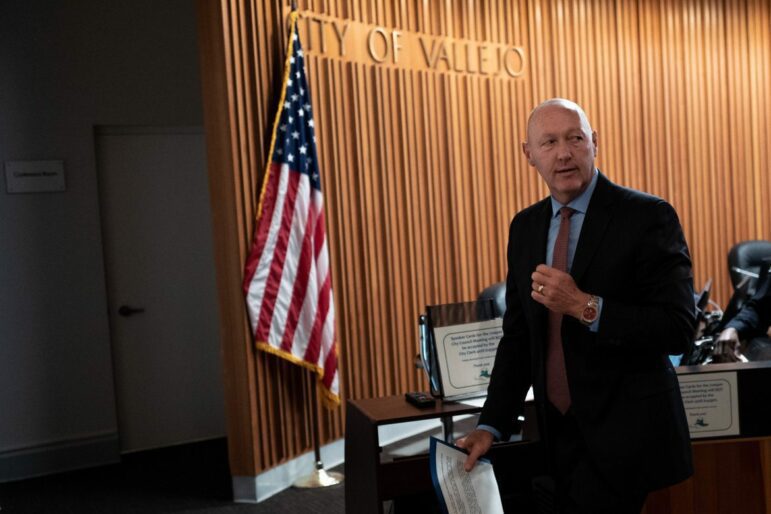

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Greg Nyhoff addresses a crowd at Vallejo City Hall in November 2019. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoThe fired staffers emphasized the clear direction they received from both city elected officials as well as the public regarding Mare Island: secure an agreement with clearly-defined objectives that must be met within specific timeframes.

In the past, property owners like Lennar have been able to keep land vacant under favorable terms that include $1-a-year leases in return for minimal benefits to the city.

“What we were hearing from elected officials, including all seven members of the council, was, ‘Put some teeth in this deal. Don’t give us another Lennar deal. We need performance guarantees,’” Morat said.

Under the October 2019 term sheet with the city, Nimitz agreed to produce “clear deliverables” every three years in exchange for enjoying exclusive rights to develop Mare Island.

In order to keep control of the land, Nimitz would have to complete construction — of housing, of retail space, and necessary infrastructure — by certain dates or lose its exclusive negotiating rights.

In other words, if Nimitz could not or would not build, and build soon, Vallejo would find someone else.

Nimitz would also assume Vallejo’s $450,000-a-year “holding costs,” bills paid to the federal government for loan repayments, property taxes, and other costs associated with Mare Island.

At the time, the council emphasized the need for “definitive” terms that “can’t be vague,” as Councilmember Hakeem Brown said during the October 22, 2019 meeting.

“At the end of the day, I can’t go out into the city of Vallejo and say, ‘I gave away this island. 900 acres, and all you had to develop was six.’ I’d be fired, and I should be fired,” Brown said. “Because we’ve sat here and played this game … my entire life.”

And Nimitz was amenable.

“The timelines hold Nimitz accountable,” said Nate Bergeron, Nimitz’s then-chief operating officer, who represented Nimitz Group at that meeting.

“What we’ve heard from the city and understand clearly is that in the past, the city has gotten into development agreements that have no teeth and have no accountability,” he added. “We want to make sure we’re holding ourselves to a higher standard and aggressive timeline.”

Bergeron did not respond to voicemails requesting comment left on his cell phone.

In a 7–0 vote, the City Council unanimously approved the term sheet, which was to have become binding in February 2020.

But that never happened.

In February, both Bergeron and Stacy Madigan, Nimitz’s former chief financial officer, abruptly left the development team.

The arrival of Southern Land, who began meeting with members of the City Council as well as city staffers in January, was announced February 5.

Madigan declined to comment for this story.

Even that October term sheet was less than what the city’s negotiators pushed for. Instead of being held to more specific construction milestones, Nimitz need only show construction had “substantially” progressed, a deliberately vague qualifier inserted into the agreement at Nyhoff’s insistence, Matzke and Morat said.

Nyhoff agrees that he resisted his employees’ pushback. If he hadn’t, he said, the developer might have been easily able to accuse Nimitz of failing to abide by the terms of the deal.

“They were concerned that if they didn’t finish it 100 percent — for example, if they were building an eight-story building, but didn’t have the drywall done, that it would not have completed the agreement, and it would allow the city to basically take it back for nothing,” he said.

But allowing the developer this leeway also allowed Nimitz to hold onto the land without producing clearly-defined significant progress, Matzke said, and amounted to an enormous giveaway to the developer.

“Fundamentally, it devalued the city’s position from a development standpoint, and had monetary impact in the tens of millions of dollars,” he said.

‘Everything went quiet’

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Vines creep up the sides of abandoned air raid shelters built on Mare Island after World War I to protect officers and their families. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoThe sudden change of personnel at Nimitz, who had spent more than a year making connections with elected officials and city negotiators as well as the public, and the timing of their exit with Southern Land Company’s arrival, also raises unanswered questions about the process.

Prior to Southern Land’s sudden appearance, there had been ongoing negotiations between the city’s team, including Matzke and Morat, and Nimitz, represented by Bergeron and Madigan.

“Then, boom, one day, everything went quiet,” Morat said. “Greg called and said, ‘Stacy and Nate are out. Southern Land Company is taking over.’”

Negotiations came to a sudden halt. “The only communications were between Southern Land and Greg,” Morat added. “He wouldn’t let us talk to Southern Land.”

That was when Nyhoff told Morat and Matzke that he’d met with Southern Land Company executives in October 2019 in Tennessee, where Nyhoff had flown to attend an unrelated conference.

In addition to cutting the city’s negotiation team out of the discussions with Southern Land, Morat and Matzke say a March 5 email between Nyhoff and Brian Sewell, Southern Land Company’s president and chief operating officer, that was sent to Nyhoff’s personal email account shows Nyhoff and the developers had a back-channel line of communication — more contact that Nyhoff did not share with his staffers or with the City Council.

Nyhoff booked his trip to Nashville in June, travel receipts and other public records show. He flew there for a planned city managers’ conference a few days early for personal reasons, he said.

Nyhoff used one of his personal days to meet with billionaire investor Gaylon Lawrence, Jr. and Southern Land Company officials at their Nashville-area offices and see some of their completed projects, he said.Such meetings are “standard” procedure for a city official negotiating with a real-estate firm, he added.

Sewell had Nyhoff’s personal email address because on Nyhoff’s trip to Tennessee, the city official wanted some Nashville-area restaurant recommendations, Nyhoff told Open Vallejo.

“At that point I said, hey, you guys, could you give me some restaurants?” he said. “That’s why I gave them my personal one, to help me.”

Nyhoff rejected the notion that any such meetings could influence the outcome of any deals, which would have to be approved by the City Council.

“I meet with developers of all projects,” Nyhoff said. “That’s just completely normal for my line of work.”

As for why he would not share news of the developer meetings with either his senior-leadership team or the City Council, Nyhoff said there is no requirement to do so. Such disclosures would be voluminous and unwelcome, he said.

“Do I think it’s necessary to be announcing to everybody who might be interested, everybody that I ever talked to or met with? The list would be quite long,” he said.

That Nimitz and Southern Land would seek Nyhoff out and also seek to influence him isn’t inherently suspicious by itself, McConnell, the incoming mayor, said, while repeating his wish that Nyhoff had told him about the meetings.

“That’s one of the things that Mr Nyhoff does need to be working on: improving openness, and discussion and keeping the public more informed,” he said.

‘False’ questions

Last summer, Southern Land Company announced that Tom D’Alesandro, an experienced real-estate project manager and the nephew of Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi, was joining the company as president and would be assuming direct supervision of the Mare Island project.

D’Alesandro has now become the developer’s point person in negotiations with the city, and was the public face of the project during the most recent council meeting.

The shifting faces at Mare Island, the vanishing term sheet and now Morat, Matzke, and Altman’s allegations about Nyhoff allegedly undermining the process are all fueling public concerns about the project.

These include questions posed by Vallejo residents both on social media and during the November 10 City Council meeting, held via Zoom, in which they expressed fears that the Mare Island project will yet again enter a period of limbo — or worse.

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

Buildings on Mare Island, as seen from a public park. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoAt least some of these questions have drawn attention from both the developers, as well as the City Council and Mayor Bob Sampayan.

Before the Nov. 10 meeting, Nimitz circulated a letter, addressed to Sampayan and the Council, that responded to a Nov. 8 anonymous email from someone calling themselves “Concerned Vallejoan.” The email outlined, among other things, the changes to the term sheet as well as the changes in personnel, painting both as problematic.

“We are happy to say that the partnership is intact and stronger than ever,” read the response from Nimitz, which was signed by Lane and Lawrence as well as Phinney. “We want to assure you that all of the claims made by ‘Concerned Vallejoan’ about the Nimitz Group in their email of November 8th are false and without merit.”

The letter did not address the 2019 term sheet, which “has to be amended,” Southern Land Company’s D’Alesandro said at the meeting.

Sampayan added his own broadside, posting a scathing retort to his Facebook page that blasted attempts “to sabotage the project with rumors, lies and falsehoods.”

“There have been a lot of questions, rumors and speculation about the Mare Island project with Nimitz Group and Southern Lands [sic] Company,” Sampayan posted under his official account. “The short answer to all the questions is that they are FALSE,” he added.

During its meeting on Nov. 10, the council also approved two $1-a-month leases with Nimitz.

For that price, Nimitz will start policing North Mare Island, an unsecured area that’s become a magnet for “numerous crimes” including illegal dumping, theft of precious metals, arson, and sideshows, according to a city staff report. Nimitz will also lease a 27.9-acre parcel on North Mare Island to store construction materials and equipment. Part of that will also be sublet to Vallejo businesses, including Kresyler & Associates, a manufacturing firm with an assembly plant on the island.

Those deals mean the city saves more than $50,000 per year, the estimated cost of policing North Mare Island. The city will also save some money on property taxes, but far less than the total $450,000-a-year holding costs that the October 2019 term sheet covered.

And Nimitz will make some money subletting out city land rent on the cheap — a point that led to a tense moment between Southern Land’s D’Alesandro and McConnell, the incoming Vallejo mayor, during the Nov. 10 meeting.

McConnell pressed D’Alesandro about whether it’s fair for the city to lease out a nearly 30-acre parcel of land for $1 a month to a developer, who then sublets it out for much more.

“We are paying all of these costs, and yes, we want to make a few nickels, but if you look at the costs, it’s not going to be a profit center for us, at all,” said D’Alesandro, who then stated the obvious: Vallejo is broke, and Southern Land isn’t.

“It’s hard to argue that you’re leaving money on the table,” he said. “You don’t have the money for the fence, you don’t have the money for the security. We just want a little assistance to allow our businesses to flourish.”

The lease was approved by a 7-0 vote.

Geoffrey King / Open Vallejo

A building on Mare Island at night. Credit: Geoffrey King / Open VallejoExactly what went on between Nyhoff and the developers may eventually come out in court. Altman, Matzke, and Morat plan to file a lawsuit over what they allege were wrongful terminations before Christmas. Depositions could begin as soon as January.

What is certain is that something has changed at Mare Island — and the city still has yet to reap significant benefits from what should be a multi-billion-dollar opportunity with the potential to relieve some of Vallejo’s most deep-seated economic woes.

Mare Island “was going to be the city’s saving grace,” Altman said. This was the thing that was going to bring Vallejo back.”

Now, she said, “there are serious concerns here.”

For many in Vallejo, the uncertain situation at Mare Island is business as usual.

“We’ve had so many false starts,” with Mare Island, Sampayan said during Southern Land Company’s formal introduction at the March 10 City Council meeting. “So many false starts.”

At that same meeting, Tim Downey, Southern Land Company’s CEO, presented a compelling vision of an alternate, prosperous future for Vallejo.

He promised to start building soon, while adding a qualifier.

California’s complex development laws are a “worry,” he said. To overcome that, he might need to call in favors.

“We’ve got to hope that doesn’t bog us down,” he said. “There may be times when we need help from the city, to help us with the state, I would think.”

He paused. “I don’t know if I even should have said that out loud, but I did,” he said.