This article was originally published by The Appeal.

On May 10, 2012, Enrique Cruz was led into a holding cell at the Vallejo Police Department after a car chase. The 29-year-old used the stainless steel toilet before peering through the rectangular window on the cell’s door.

A few minutes later, Detective Kent Tribble opened the door. Cruz, who was dressed in a dirty white T-shirt and baggy gray pants and had his long brown hair in a ponytail, took two large steps back. He turned around and put his hands behind his head. Tribble patted him down.

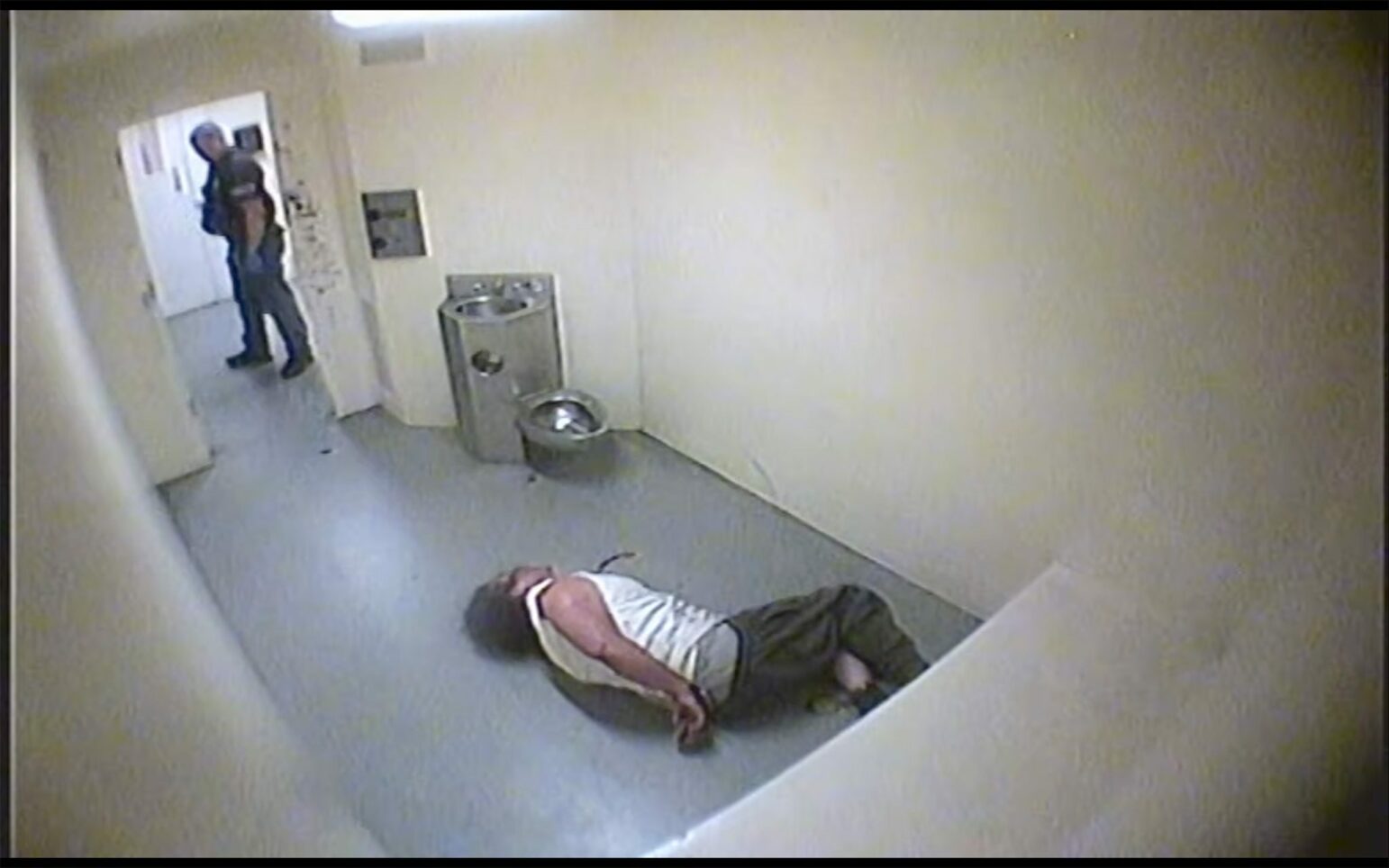

According to a jail cell video obtained by The Appeal, Tribble stood over Cruz as he sat on the cell’s white bench with his arms folded. Then Cruz put his hands up, palms out, before Tribble lunged at him, slamming him against the concrete wall. Tribble punched Cruz in the head twice before Officer Eric Jensen entered the cell. They put their arms around Cruz’s neck and head before wrestling him to the floor.

Tribble punched Cruz about half a dozen more times as officers Joshua Coleman, Jared Jaksch, James Melville, and Jason Potts ran into the cell and piled on him. After the officers placed Cruz in handcuffs and in leg chains, Tribble stood up and walked around the cell. Then Jensen put his knee on Cruz’s neck, rendering him nearly motionless on the concrete floor as he bled from his head.

Later, Cruz was charged, along with felony evading and DUI, for resisting Tribble and Jensen, although prosecutors from the Solano County district attorney’s office subsequently dropped the resisting charge.

Tribble did not face any disclosable disciplinary action from the Vallejo Police Department in the Cruz incident. The Appeal checked federal and state court records, and there is no record of a lawsuit brought against Tribble on behalf of Cruz. The city attorney’s office has no record of a settlement paid to Cruz.

Michael “Kent” Tribble is now a lieutenant with the Vallejo Police Department — and he has a history of force beyond the Cruz incident that includes killing an allegedly unarmed man and allegedly putting a gun to a man’s face outside an Oregon bar while off duty.

Despite these incidents, Tribble has been promoted by two Vallejo police chiefs and, according to the city attorney’s office, has no disclosable disciplinary records. California prohibited the disclosure of all police disciplinary records until recently, when a new law required departments to release them when an officer fires a gun, uses force that resulted in death or serious injury, commits sexual assault, or engages in dishonesty. Tribble earns more than $400,000 a year in salary and benefits. His bio on the department’s new website is blank.

“He had the type of personality where he really got off on the power and the violence. And he just hurt and destroyed so many people,” said Cheryl McLandrich, a former deputy public defender in Solano County, where Vallejo is located. “I’m just absolutely amazed that they put him in a position of authority.”

Tribble declined to comment when contacted by The Appeal, and referred all questions to the police department’s public information officer.

“The City has no disclosable records related to discipline against Lt. Tribble,” public information officer Brittany K. Jackson wrote in an email to The Appeal. Jackson declined to comment on the specific incidents involving Tribble described in this article.

Tribble — whose brother, Robert “Todd” Tribble, is now also a lieutenant with Vallejo police — is among the command staff of the San Francisco Bay Area’s most violent police department. The force of about 100 officers for a city of 120,000 residents had the third-highest rate of police killings per capita in California between 2005 and 2017, according to the local NBC affiliate.

In 2012, Vallejo police killed six people, about 20 times the rate in both Oakland and San Francisco that year. In April of 2012, the Solano County DA cleared Tribble in the fatal shooting of Guy Jarreau Jr. A month later, his assault of Cruz in the holding cell was captured on tape and reviewed by the DA’s office.

In 2019, The Appeal reported that Vallejo police supervisors who reviewed shootings for potential policy violations praised officers for their use of the “zipper drill” in which an officer “fires numerous rounds into an adversary, starting low in the target’s body and ‘zipping’ the barrel of the gun up toward the person’s head while continuously shooting.”

Until recently, no Vallejo police officer was known to have been terminated in connection to the department’s 19 fatal shootings in the last decade. On Sept. 1, Vallejo’s current police chief, Shawny Williams, issued a notice of termination to Officer Ryan McMahon after an Internal Affairs investigation found he engaged in “unsafe conduct and neglect for basic fire safety” that put his fellow officers at risk during the February 2019 shooting death of Willie McCoy. Six officers were involved in the killing of McCoy, who was asleep in his car in a Taco Bell drive-thru when officers fired 55 bullets at him. Michael Ramos, a former San Bernardino County district attorney and special prosecutor hired to review the case, recently determined the officers were justified.

On Feb. 13, 2018, McMahon also beat, tased, and shot Ronell Foster to death for riding his bike at night without a light. The city settled a lawsuit with Foster’s family for $5.7 million last year, the largest settlement of the nearly $16 million Vallejo has paid out for claims against its police department. Facing another $50 million in legal claims and federal civil rights lawsuits, the city declared a “public safety emergency” in October, temporarily cutting the Vallejo Police Officers Association (VPOA) out of key decision-making processes. The union called it “an illegal power grab.”

Last year, two other lieutenants — including the president of the VPOA — were placed on leave related to allegations of evidence destruction in the June 2 killing of 22-year-old Sean Monterrosa of San Francisco.

Early that morning, in the midst of the George Floyd protests and widespread looting in Vallejo, Detective Jarrett Tonn responded to a report of possible looting at a local Walgreens. Outside the store, Tonn fired five shots from his tactical rifle from the backseat of an unmarked police truck, killing Monterrosa. In body camera footage, Tonn said: “Hey, he pointed a gun at us.” But Monterrosa was carrying a hammer in his sweatshirt.

In August, Monterrosa’s family filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Tonn and the city of Vallejo. The lawsuit alleges that Tonn was involved in at least three nonfatal shootings within the past five years. According to the suit, in 2015 Tonn fired his weapon 18 times in two seconds while trying to arrest Gerald Brown, who was allegedly in a stolen vehicle ramming his police vehicle. Brown survived the shooting. In October, the city of Vallejo responded to the lawsuit, arguing, among other things, that Tonn is entitled to qualified immunity.

The California Department of Justice is also reviewing allegations of destruction of evidence in the Monterrosa case by Vallejo officers as well as conducting a broad review of the department’s policies.

“The allegations concerning destruction of evidence under the watch of the Vallejo Police Department are significant,” Attorney General Xavier Becerra said in a statement last summer. “For public trust to exist, each and every part of our criminal justice system must operate in cohesion and there’s little room for error. That’s why we’ve accepted Chief Williams’ request to take a look at what happened with the evidence and relay our findings to the District Attorney’s Office for review.”

Last year, a former Vallejo police captain said he’s filing a whistleblower lawsuit after he says he was fired for reporting unlawful and unethical behavior at the department, including officers bending their badges to commemorate shootings, as first reported by Open Vallejo.

The Vallejo Police Department hired Tribble on March 24, 2003, just three months after it hired his brother, Todd.

In August of that year, Tribble and other officers were involved in the fatal shooting of 27-year-old Kevin Laron Smith. David Paulson, the district attorney at the time, cleared all the officers in the shooting and the department used the shooting to make a 20-minute training DVD.

The following month, Tribble beat Regynald Jackson, a 49-year-old disabled former Travis Air Force Base employee, in the head with his baton and broke Jackson’s leg in two places before the baton broke. Jackson was handcuffed behind his back when Tribble assaulted him, according to a federal civil rights lawsuit filed in 2005. Jackson was charged with resisting arrest and battery upon a police officer, but he was acquitted at trial. In 2007, the city settled Jackson’s lawsuit for $27,500.

On Feb. 26, 2006, Tribble responded to a call about three men arguing in a vacant lot near 309 Kentucky St. When he arrived, Tribble went around the side of the house, and when his shoulder mic went off, a man inside, Manzell Wesley, yelled out of the window to see who was there.

“It seems like a fairly normal reaction to say, ‘Who’s there?’ and to be alarmed if you hear someone sneaking up around the back window of your home,” said McLandrich, the public defender assigned to Wesley’s case.

Tribble tased Wesley three times through the window. Wesley was charged with resisting arrest. Later, Tribble testified that Wesley threatened his family, an allegation disputed by a resident at the home. A judge dismissed the resisting charge.

McLandrich said that before Vallejo implemented body cameras in 2015, it was “almost impossible” to beat a charge where an officer said someone made a threat against them. “They would do that all the time to justify their actions, and I am extremely skeptical that such a threat ever took place,” she said.

McLandrich said Tribble was known for physical aggressiveness, which earned him the nickname “Captain Taser” among prosecutors.

In March 2006, less than a month after Tribble tased Wesley, he and Officer Jeremie Patzer deployed their Tasers on Jimmy Merlos for allegedly not putting his hands up. McLandrich represented Merlos, and she said police reports of the incident contained omissions and false statements, such as claims that Merlos did not attempt to put his hands up, when he attempted to do so as Tribble and Patzer tased him. Merlos nonetheless received three years of probation.

In July 2006, Eric Garfield Williams was pulled over in North Vallejo. In a lawsuit filed in federal court, Williams alleged that Tribble, Officer Sean Kenney, and Corporal Richard Botello repeatedly hit him while he was in handcuffs. Williams said Tribble banged his face on the pavement until he was unconscious and defecated and urinated in his pants. In 2012, a judge dismissed Williams’s lawsuit.

On Oct. 8, 2006, Terry Jasper went to Kaiser Permanente Vallejo Medical Center after learning his son had been injured in a car accident. After Tribble told him he wouldn’t be able to see his son, Jasper went to the bathroom where “Tribble followed him in, threw him against the wall, and placed him in a choke hold,” according to a statement his attorney submitted in Solano County court.

Tribble claimed in his report that Jasper was fleeing, drunk, and combative, but Jasper denied drinking that day. In statements submitted to the court, witnesses said Tribble attacked Jasper unprovoked and later threatened Jasper’s nephew with his baton.

Jasper was charged with public intoxication and disturbing the peace. McLandrich was assigned to his case and became skeptical of the police’s version of events because Tribble’s name was on the report. A judge granted her a Pitchess motion — a defendant’s request under California law to inspect a law enforcement officer’s personnel file for evidence of police misconduct — but Tribble’s file remains under seal. The charges against Jasper were dismissed in November 2007.

“It’s so fucked up to put someone in the position where anywhere these officers can make a statement that you did anything or said anything that could result in these charges and allowing them to have impunity for beating the shit out of you,” McLandrich said. “Obviously, it didn’t hurt his career too much.”

On Dec. 11, 2010, Tribble shot and killed 34-year-old Guy Jarreau Jr., a New Orleans native who lived in Vallejo for the last eight years of his life, according to his obituary. In clearing Tribble of any criminal wrongdoing, then-Solano County District Attorney Donald du Bain wrote that investigators found Jarreau fled a crime scene with a firearm and drew it when Tribble cornered him in an alley. Tribble was promoted to detective the following year.

Jarreau’s family, however, alleged he was helping fellow Napa Valley College classmates make an anti-violence video when Tribble pulled up in an unmarked vehicle wearing plain clothes and gave no warnings before shooting Jarreau. According to a federal lawsuit, Jarreau was holding a green cup when he was shot while he had hands in the air and Tribble unnecessarily waited to get him medical attention. The city settled the suit for $49,000 in 2017.

Tribble fired his gun again on duty in April 2012 while allegedly trying to protect now-Captain Jason Potts during an undercover cannabis deal. Tribble did not hit his intended subject.

In the fall of 2012, Robert Wilson lived with his wife and teenage son at 1251 Locust Drive in Vallejo. A neighbor complained that they were squatting, so on Oct. 17, Tribble and other members of a Vallejo police tactical unit traveled to the residence to forcibly remove them.

Tribble later testified that he threw a flash bang into the doorway while Wilson was trying to close the door on them.

Felicia Carrington, Wilson’s public defender, told The Appeal that Wilson was going to the door to see why his dog was barking when police tried to enter the house.

“They hit him in the head. I mean like no conversation whatsoever and they shoot and kill his dog,” she said. “The way it played out was so overly aggressive and unnecessary.”

Carrington said Wilson was proficient in martial arts and tried to defend himself against the assault, so Tribble hit him in the head with his rifle as now-Sergeant Jared Jaksch shot Wilson with a less-lethal projectile.

“And that really apparently pissed them off. They broke his leg,” Carrington said. “And then he went down on the ground, they had him on his stomach, and he started saying the Lord’s Prayer.”

During her questioning of Tribble at Wilson’s trial in October 2016, Carrington alleged that Tribble knelt down to Wilson and before spitting in his face said, “There ain’t no God. I am your god.” Tribble denied that he made the comment or spit on Wilson, but Carrington said Tribble became visibly upset when she asked about his prior discipline for using excessive force.

“He came unglued. He was so pissed off,” Carrington said. She remembered that Tribble slammed the wooden gate to the galley and the door on his way out of the courtroom. “It was a sight. It was so unprofessional and so telling of what he does and who he is. You can’t regulate yourself in front of a judge and a jury? I can’t imagine what some of our clients have experienced with him. It’s scary.”

But Carrington wasn’t done exploring Tribble’s violent history. In Wilson’s trial, she also wanted to raise an off-duty incident involving Tribble in Oregon two years after he entered Wilson’s home, and a year after he was promoted to sergeant and became the assistant leader of Vallejo’s SWAT team. His brother was the team’s commander at the time.

On Sept. 27, 2014, Stuart Epps and Dustin Pomeroy were celebrating their birthdays with a group of friends in Bend, Oregon. The first bar they visited that night was Summit Saloon, where Tribble and retired Vallejo police officers Kevin Coelho and Kevin McCarthy were drinking upstairs.

“They stuck out like sore thumbs,” Epps told The Appeal.

Pomeroy testified in 2016 that the officers stared at his friend’s then-fiance. When his friend said something about it, Tribble allegedly gripped his face in the palm of his hand and shoved him into a group of people. Security broke up the fight.

After a drink at another bar, Epps decided to run ahead of his friends to the next nightspot. That’s when he encountered Tribble, Coelho, and McCarthy again.

“I was pretty much pummeled to the ground,” Epps later testified, claiming that Coelho put him in a chokehold. “And as things fade to black, officer Tribble had his pistol at the end of my nose.”

Pomeroy testified that he saw Epps being punched and kicked while unconscious, and that Tribble punched Epps in the head up to five times before pointing his gun at Epps’s head.

“I’ll fucking kill you!” Pomeroy testified Tribble said.

“I just remember being pummeled to the ground and then a pistol, literally at the end of my nose, while I was being choked out unconscious,” Epps recently told The Appeal.

Cell phone video shows Tribble later standing over Epps, who remained unconscious on the sidewalk. “Fuck you, you little pussy,” Tribble yelled as he walked away.

Bend Police let everyone go. Epps looked Tribble up after a local TV station identified him.

“Are you fucking kidding me? That’s who I just ran into?” Epps remembers thinking. “It gave me a good deal of anxiety and paranoia. The promotion thing is bullshit. His ass should have been fired well before he came to Bend.”

Epps says the Vallejo Internal Affairs officer who followed up with him offered an apology, but he never heard more on the department’s response and local authorities didn’t charge anyone in the incident. Epps was twice contacted by attorneys representing clients in cases involving Tribble, the last being Carrington.

Epps and Pomeroy flew to the Bay Area to testify in Robert Wilson’s trial in October 2016, but Solano County Superior Court Judge Daniel J. Healy wouldn’t let the jury hear their testimony. He did warn Solano County Deputy District Attorney Judy Ycasas that her office should “take some ownership” of such accusations against Tribble when calling him to testify.

“I think there probably is going to be an occasion when this information is going to be relevant and admissible against Tribble,” Healy said. “But this isn’t it.”

The judge’s decision frustrates Epps and Carrington, who say they want juries to learn about Tribble’s conduct.

“It’s next to impossible to bring that before jurors,” Carrington said. “But I think now, in this time, people are more receptive to it and willing to actually believe it, if we can get that information in front of them. It’s just very difficult and frustrating.”

In January 2017, three months after Epps and Pomeroy testified in open court — not before a jury — about Tribble’s alleged conduct in Bend, then-Police Chief Andrew Bidou promoted Tribble to lieutenant, where he has also served as a department spokesperson. Tribble is now one of four lieutenants, including his brother, overseeing the department’s patrol division.

Bidou, who now works for the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, did not reply to a request for comment from The Appeal.

Tribble has also worked in Internal Affairs, investigating and clearing officers involved in fatal shootings who then commit further acts of force.

Carrington told The Appeal that when cases are built on the testimony of a certain group of Vallejo officers — Tribble among them — they deserve extra scrutiny.

“Every time you saw that name on that police report, you knew there was going to be some aggressive conduct or you would have to delve even deeper,” she said. “You’re gonna take more time on this particular case, because there were some underlying issues, almost always.”

One of the lawsuits pending against the Vallejo Police Department demands that it be put under the oversight of a federal monitor because of its “unconstitutional conduct,” just like nearby Oakland.

Puneet Cheema is the manager of the Justice in Public Safety Project for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which pushes for accountability for police brutality and misconduct through community oversight and changes to laws and policies, among other things. Cheema told The Appeal there’s historically been a failure of internal and external accountability and oversight in the 18,000 independently run police departments in the U.S.

Cheema says although there has been a vacuum of federal oversight of troubled departments under the Trump administration, the Biden administration has the opportunity to take police misconduct seriously.

“When there are robust investigations, it sends a signal to other police departments of what will not be tolerated and what the standard should be for conduct,” Cheema said. “And that has a ripple effect where at least some agencies will proactively take measures to shore up their internal systems. There will always be agencies that resist that need more direct pushing.”